The ideal amount of sleep we need each night varies from person to person, but the exact relationship between sleep and genetics still isn't clear – something that a new study on populations of fruit flies might help to shed light on.

A small group of genes was identified that seems to be linked to variations in sleep duration, and which is also tied to important cell pathways linked to brain development, learning, and memory.

If the same findings can be replicated into human beings, then it gives experts another avenue for targeting sleep-related health issues such as insomnia and narcolepsy, according to the team from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in Maryland.

(NHLBI)

(NHLBI)

"This study is an important step toward solving one of the biggest mysteries in biology: the need to sleep," says lead researcher Susan Harbison. "The involvement of highly diverse biological processes in sleep duration may help explain why the purpose of sleep has been so elusive."

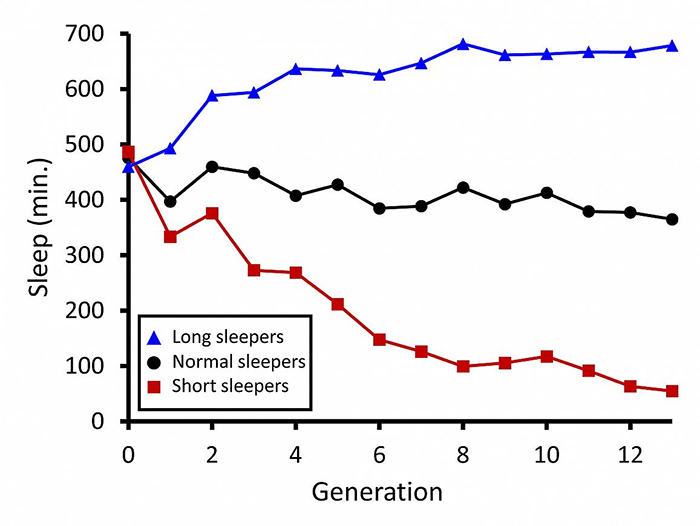

Using 13 generations of wild fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), the scientists bred one group of flies that loved to nap (by mating long sleepers with other long sleepers) and one group of flies that didn't need much sleep at all (by mating short sleepers with other short sleepers).

By the end of the experiment the long-sleeping fruit flies were getting almost 700 minutes of kip each day on average, while the short sleepers settled for less than 100 – think how many extra Netflix episodes you could fit in with less than two hours of sleep a night.

When genetic data from the long and short sleepers was compared, the scientists identified 126 differences in 80 genes that appear to be linked to how much sleep was needed each night.

With more research, that could give us clues as to how genetics affects sleep and the biological processes that underpin our slumber.

Fruit flies not only share many of our genes, they're also low maintenance and have very short life spans, making them perfect for studies such as this.

"What is particularly interesting about this study is that we created long and short-sleeping flies using the genetic material present in nature, as opposed to the engineered mutations or transgenic flies that many researchers in this field are using," says Harbison.

"Until now, whether sleep at such extreme long or short duration could exist in natural populations was unknown."

Another finding to emerge was that the lifespan of the long and short sleepers didn't vary much from the normal group. Perhaps as long as you get the amount of sleep your own individual body needs, the physiological effects are minimal – at least if you're a fruit fly.

While there are no hard and fast takeaways from this particular study, it's another useful step towards understanding just how our genes affect how much sleep we need, and how they relate to the other biological cycles of the body.

It also gives us a glimpse at how far in either direction the ideal sleep duration could be pushed by genetic variations alone.

The scientists themselves describe sleep as a "classic enigma" of biology: the way that better sleep can improve memory formation, and lack of sleep can start eating away at our brains, plus a host of other processes and consequences that we don't understand yet.

Previous studies in humans have already identified one particular gene mutation that can cause people to be natural night owls, while seven other genes have been linked to problems with insomnia, a finding that could potentially improve treatments.

There's a lot more to discover, and this research might point the way.

"The study of naturally-occurring genetic variation as implemented here can be manipulated to gain insights on the genetic basis of complex physiological traits and disease," conclude the researchers.

The findings have been published in PLOS Genetics.