Precious stones might be relatively rare and hidden deep underground here on Earth, but space is an absolute treasure chest. Astronomers have found a new class of planets, and they're so abundant in the compounds that make sapphires and rubies, they could be positively sparkling.

These planets are a type of super-Earth - dense planets like Earth and Mars, with a high proportion of rock, metal or a combination of both, only much bigger (but still smaller than Neptune).

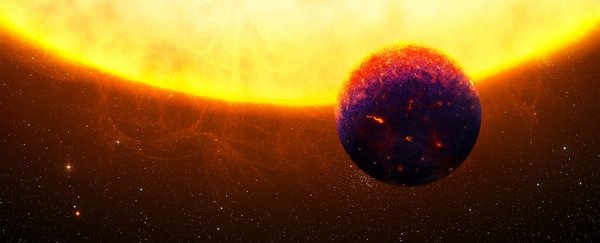

However, this group tend to orbit their stars much, much closer than Earth, or even most super-Earths. That means, if they orbit where they were formed, their composition could be very different. Rather than an iron core like Earth's, they are abundant in calcium and aluminium.

This, in turn, could mean the presence of rubies and sapphires, which are made of the mineral corundum - a crystalline form of aluminium oxide.

Researchers from the Universities of Zurich in Switzerland and Cambridge in the UK have identified three planets that may be of this hot super-Earth type.

They are: HD 219134 b, located just 21 light-years away, in the constellation of Cassiopeia, with an orbit of just 3 days; 55 Cancri e, 41 light-years away, with an orbit of just 18 hours; and WASP-47 e, located 870 light-years away, also with an 18-hour orbit.

Planets are made of the leftover disk of dust and gas swirling around a newborn star, called a protoplanetary disc. Electrostatic forces start to bind particles of dust and gas orbiting the star into clumps; gradually, these accumulate until they have enough gravity to attract even bigger pieces, and, if everything works out, it will collect enough mass to form a planet.

Farther out in the disc, elements such as silicon, iron and magnesium have condensed, and this, according to planetary scientists, results in compositions like those of Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars.

But when you get really close to the star, it is, of course, much, much hotter. So any planets born here are not going to be like Earth.

"Many elements are still in the gas phase there and the planetary building blocks have a completely different composition," explained astrophysicist Caroline Dorn of the University of Zurich.

She and her team conducted simulations, and found that, alongside silicon and magnesium, aluminium and calcium are the most abundant components. There's hardly any iron.

Planetary magnetic fields are generated by a liquid conductive core which, in theory at least, doesn't need to be ferrous. But these planets, according to the team's simulations, would have no core at all - and therefore no magnetic fields, or at least magnetic fields completely unlike those found surrounding the Solar System's planets.

Their internal structure would also be quite different, and therefore atmospheric conditions and cooling would be different, too.

"What's exciting is that these objects are completely different from the majority of Earth-like planets," Dorn said.

For a start, their densities would be 10-20 percent lower than Earth's density, and because they orbit so close to their stars, this could not be explained away by thick atmospheres, at least on 55 Cancri e and Wasp-47 e - they are so hot that their atmospheres would have burned away.

HD 219134 b is a little bit farther out, so its lower density could be the result of magma oceans, although the researchers were unable to conclusively identify whether magma oceans can have this effect.

"Perhaps [HD 219134 b] shimmers red to blue like rubies and sapphires,"says Dorn. But, while the planets are good news for lovers of all things sparkly, there's some slightly disappointing news for diamond fans.

That's because 55 Cancri e had previously been identified as a planet made of diamond in 2012, a conclusion the team now says was erroneous. The carbon abundance that could have produced that incredible result, they say, was not supported by subsequent observations.

But nothing has yet contradicted the finding that it could be raining diamonds on Neptune. Between these corundum-rich hot super-Earths, Neptunian diamond rain, and corundum clouds on a hot Jupiter, the galaxy is turning out to be quite a glittering treasure trove.

The team's research has been published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.