You can't see them from the surface, but they're definitely there. Scientists have revealed the discovery of hundreds of ancient ceremonial sites, many of which belonged to the Maya civilization, hiding in plain sight just underneath the landscape of modern-day southern Mexico.

The largest of these structures – called Aguada Fénix – was announced by archaeologists last year, representing the oldest and biggest monument of the ancient Maya ever found. But Aguada Fénix clearly was not alone.

In a new study, an international team of researchers led by anthropologist Takeshi Inomata from the University of Arizona reports the identification of almost 500 ceremonial complexes tracing back not just to the Maya, but also to another Mesoamerican civilization who made their mark on the land even earlier, the Olmecs.

As with the discovery of Aguada Fénix, the sites identified in the new analysis (478 in total) were found the same way: using LIDAR, which combs the land with lasers during an aerial survey, detecting three-dimensional archaeological structures buried beneath vegetation and other surface features.

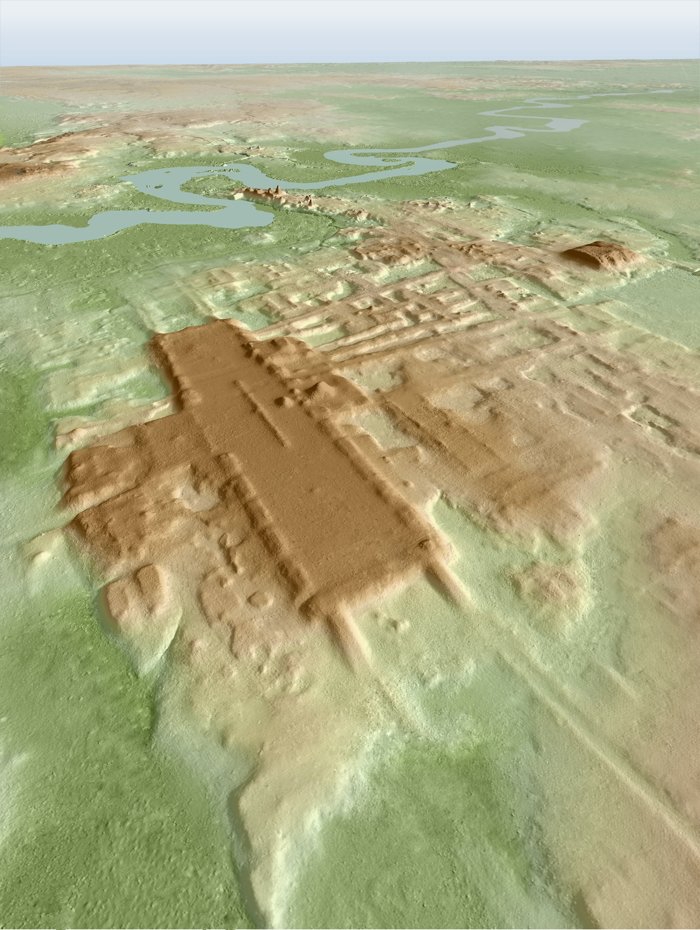

3D image of the site of Aguada Fénix based on LIDAR. (Takeshi Inomata)

3D image of the site of Aguada Fénix based on LIDAR. (Takeshi Inomata)

In this case, the LIDAR data were already publicly available, courtesy of Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography, and covering a sprawling 85,000 square-kilometer area (about 33,000 square miles).

When Inomata and his team analyzed the dataset, they identified hundreds of ceremonial sites scattered across the Mexican states of Tabasco and Veracruz, most of them previously unknown.

Most of the new discoveries are much smaller than the sprawling Aguada Fénix – which measures over 1,400 meters (almost 4,600 ft) in length at its greatest extent – but even so, seeing them for the first time reveals a mysterious design influence that hadn't been fully appreciated before in Maya structures.

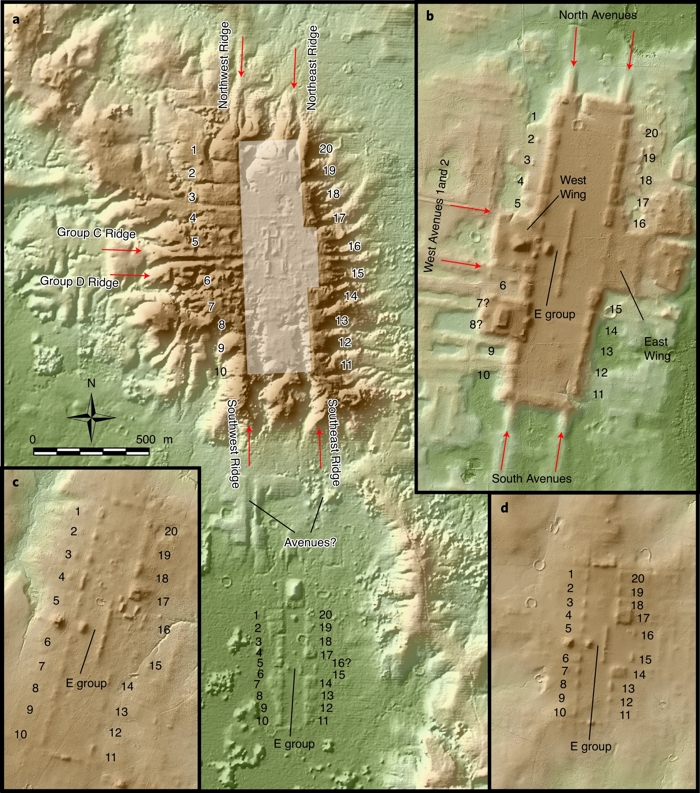

According to the researchers, a previously unseen layout in the ancient Olmec city San Lorenzo – the oldest Olmec urban center, dating to around 1150 BCE – can be seen as a recurring motif in later structures built by the Maya, which echo San Lorenzo's central rectangular space, adopting its "spatial template".

"People always thought San Lorenzo was very unique and different from what came later in terms of site arrangement," Inomata says.

"But now we show that San Lorenzo is very similar to Aguada Fénix – it has a rectangular plaza flanked by edge platforms. This tells us that San Lorenzo is very important for the beginning of some of these ideas that were later used by the Maya."

(Inomata et al., Nature Human Behaviour, 2021)

(Inomata et al., Nature Human Behaviour, 2021)

Above: Comparison of the San Lorenzo rectangular hallmark (top-left) and MFUs in other structures (with Aguada Fénix top-right).

If so, the architecture at work here reveals an important link between these two distinct civilizations, which partially overlapped in time but also peaked in different chapters of Mesoamerican history, with the Olmecs flourishing in what's known as the Formative period (2000 BCE–250 CE), while the Maya grew in dominance (and structural ingenuity) in the Classic period (250–900 CE).

The rectangular complex design, which the team calls the Middle Formative Usumacinta (MFU) pattern, and its related variants, suggest inter-regional interactions and influences between the Olmecs and the Maya were more complicated and diverse than we realized.

"The presence of this previously unrecognized pattern implies that the emergence of standardized ceremonial complexes in southern Mesoamerica was more complex than previously thought," the researchers write in their paper.

In addition to analyzing LIDAR data, the team also conducted preliminary ground observations on foot at 62 of the sites, which on the whole are estimated to date from around 1,050–400 BCE, and are thought to have been used as ritual spaces, where people gathered to meet, and to watch processions.

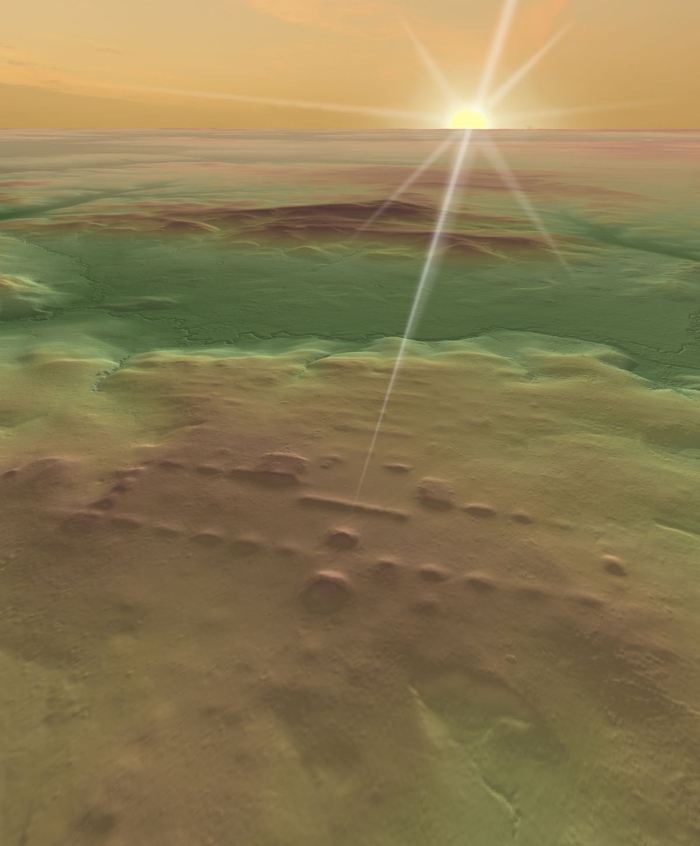

LIDAR-based image of the Buenavista ceremonial site. (Takeshi Inomata)

LIDAR-based image of the Buenavista ceremonial site. (Takeshi Inomata)

Some of the sites are oriented to align to the sunrise on certain dates in Mesoamerican calendars, suggesting the ritual processes involved cosmological concepts tied to the movements of the seasons.

"This means that they were representing cosmological ideas through these ceremonial spaces," Inomata says. "In this space, people gathered according to this ceremonial calendar."

While there is still much we don't yet understand about the significance, history, and evolution of these hundreds of ritual complexes – with the discoveries posing years of investigations ahead for archaeologists and anthropologists – it's clear the Olmecs and the Maya may have shared more than we realized, literally building their societies and cities alongside one another.

"There has always been debate over whether Olmec civilization led to the development of the Maya civilization or if the Maya developed independently," Inomata said last year. "So, our study focuses on a key area between the two."

The findings are reported in Nature Human Behaviour.