We're now increasingly aware of the microplastic fragments polluting our oceans, but a new study shows just how quickly these tiny particles can find their way into marine life – it takes a mere six hours for billions of pieces of material to spread inside aquatic animals.

The unfortunate critters involved in the research were great scallops (Pecten maximus), and scientists used several of them in specially prepared water designed to match the world's oceans in terms of plastic content.

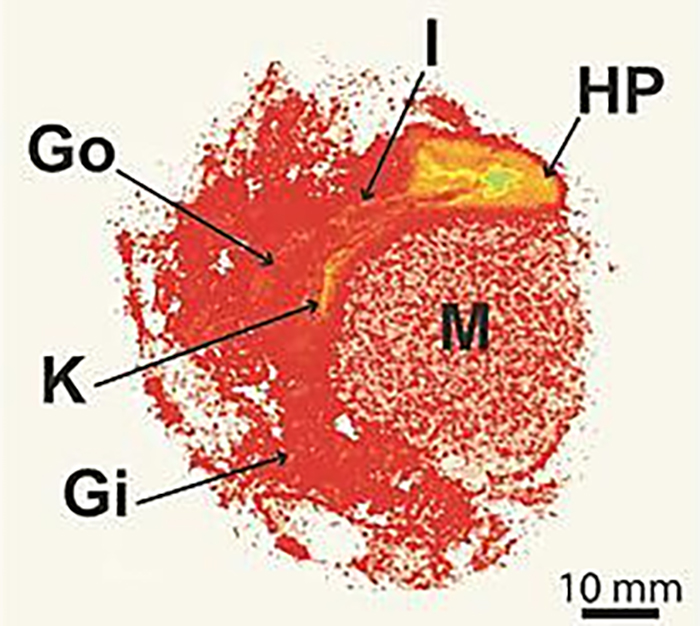

After six hours, billions of 250-nanometre particles had seeped into the intestines of the scallops, the study showed. An even higher number of 20-nanometre particles had found their way into the rest of the mollusc's body, including around the kidneys, gills, muscles and other organs.

Plastic particles in the scallop. (University of Plymouth)

Plastic particles in the scallop. (University of Plymouth)

There is one small silver lining – when the great scallops were put back into clean water, most plastic traces disappeared in days, with some sticking around for a couple of months – but it's not much consolation when it comes to the overall picture of pollution.

"The results of the study show for the first time that nanoparticles can be rapidly taken up by a marine organism, and that in just a few hours they become distributed across most of the major organs," says lead researcher Maya Al Sid Cheikh, from the University of Plymouth in the UK.

Where this experiment differs from many previous ones is in the way it matches the level of microplastic content thought to exist in the ocean – 15 micrograms of plastic per litre – therefore making it more relevant for real-world conditions.

Very tiny fragments of custom-made polystyrene, labelled with radioactive traces, were mixed with the algae that the scallops fed on. A technique called autoradiography was then used to measure the dispersal of these fragments inside the scallops.

"This is a ground-breaking study, in terms of both the scientific approach and the findings," says one of the team, Richard Thompson from the University of Plymouth.

"We only exposed the scallops to nanoparticles for a few hours and, despite them being transferred to clean conditions, traces were still present several weeks later."

What we don't yet know is just what effect this is going to have on marine life and on animals further up the food chain (like human beings).

The rapid spread of the plastics is positive in the sense that they wouldn't necessarily stick around, the scientists say – they estimate that around 300 days of this sort of exposure would be needed for the plastics to become more permanently lodged in tissue, and then at a concentration of less than 2.7 milligrams per gram.

But with 51 trillion microplastic fragments already thought to be out in the sea, this is a problem that looks like it will only get worse. The warning signs are there, and it's up to us to change our behaviour before the situation can't be reversed.

"Understanding whether plastic particles are absorbed across biological membranes and accumulate within internal organs is critical for assessing the risk these particles pose to both organism and human health," says one of the researchers, Ted Henry from Heriot-Watt University in the UK.

"The novel use of radiolabelled plastic particles pioneered in Plymouth provides the most compelling evidence to date on the level of absorption of plastic particles in a marine organism."

The research has been published in Environmental Science and Technology.