It's called Pando, a forest of around 47,000 genetically identical quaking aspen trees that share an estimated 8,000-to-12,000-year-old root system.

Pando's home is in south-central Utah in the United States, and it's one of the world's largest - and oldest - living organisms. It's also failing to regenerate.

"People are at the center of that failure," ecologist Paul Rogers of the Western Aspen Alliance and Utah State University told Gizmodo.

Quaking aspens (Populus tremuloides) are among the most peculiar of trees. They usually reproduce asexually from an underground root system. Each stem belongs to that single root system, and aspen groves are rarely made up of genetic individuals.

Instead, they are clonal colonies of genetically identical stems, known as ramets - although none has approached the sheer size of Pando (Latin for "I spread"), aka the Trembling Giant.

It weighs an estimated 5.9 million kilograms (13 million pounds) and covers around 43 hectares (106 acres) of ground in Utah's Fishlake National Forest. It's not quite the largest living organism – that honor goes to a 965-hectare (2,384-acre) fungus in Oregon – but it is up there in the charts.

Because it's so unusual, Rogers and his team have been monitoring it, and they've just completed the first complete assessment of Pando's health.

The news is not good – their results show decades of deterioration.

More specifically, over the last 30 or 40 years, Pando has not been producing enough young stems to replace old growth; grazing animals eat them faster than they can grow.

So why is this human fault, then? Well, partially because we knew that fencing the forest to protect it from these animals would help. An early project to fence part of the forest showed promise – but then there was no follow-up, leaving most of the area unprotected.

And the team found that the passive fencing used was penetrable by animals, so it probably played a role in the forest's inability to regenerate.

"After significant investment in protecting the iconic Pando clone, we were disappointed in this result. In particular, mule deer appear to be finding ways to enter through weak points in the fence or by jumping over the eight-foot barrier," Rogers said.

"While Pando has likely existed for thousands of years – we have no method of firmly fixing its age – it is now collapsing on our watch. One clear lesson emerges here: we cannot independently manage wildlife and forests."

(Rogers & McAvoy, PLOS One, 2018)

(Rogers & McAvoy, PLOS One, 2018)

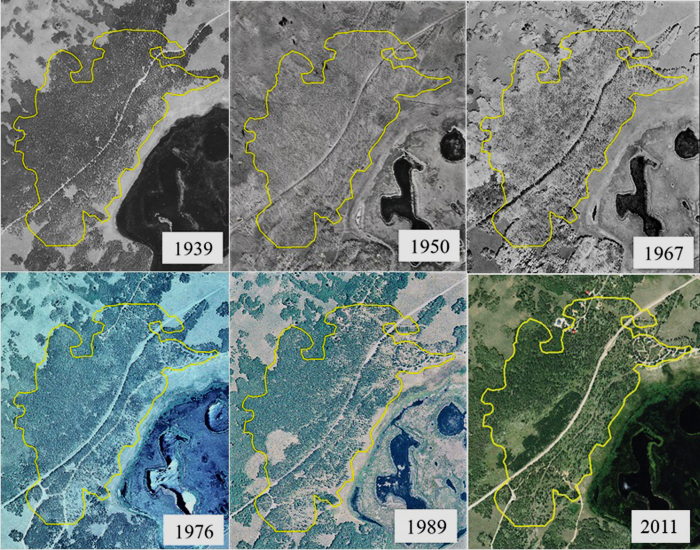

That's not all. The study, for the first time, shows the impact of 72 years' worth of human development in Pando's territory via aerial photos. While it's recovering in parts, regions cleared by humans for homes and camping grounds still remain deforested today.

And humans are also responsible for the increased presence of deer, whose population has been steadily growing in Utah, in part because of the suppression of their natural predators in the region, such as wolves and bears; because hunting is discouraged in recreation areas such as Pando, they've been unable to make up the shortfall.

"Extrication of wild predators and prohibitions on hunting near recreation sites facilitated a 'refuge affect' for ungulates that are accustomed to people (mule deer, cattle) while discouraging those that are not (Rocky Mountain elk)," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"This altered pattern roughly coincides with our 72-year photo sequence, when increases in road traffic, recreational home development, and campground use have flourished."

With its mature population of ramets reaching the end of their natural lifespan of 100-130 years, what the forest needs is a bit of time to allow the new growth to reach a level of robustness that can survive grazing deer.

Options include temporary fencing that is a little better at keeping the deer at bay; temporary access to professional hunters to reduce deer numbers; or a combination of the two.

"In addition to ecological values, Pando serves as a symbol of nature-human connectedness and a harbinger of broader species losses. Here, regionally, and indeed internationally, aspen forests support great biodiversity," Rogers said.

"This work further argues for 'mega-conservation' as a departure from traditional individual species-habitat approaches. It would be shame to witness the significant reduction of this iconic forest when reversing this decline is realizable, should we demonstrate the will to do so."

The research has been published in the journal PLOS One.