Editor's note (8 November 2023): Nature has now retracted the paper. You can read more here.

Editor's note (27 September 2023):Co-authors on this paper have asked for it to be retracted due to flaws in the report.

Original story: Few discoveries in science would revolutionize technology as much as a material that achieves superconductivity at room temperature, under relatively mild pressures.

A team of physicists led by Ranga Dias, a physicist from the University of Rochester in New York now claims they might have cracked it, demonstrating a rare earth metal called lutetium combined with hydrogen and nitrogen can conduct electricity without resistance at 21 degrees Celsius (70 degrees Fahrenheit) and around just 10,000 atmospheres of pressure, the team reports.

That may sound like it's still an unusably high amount of pressure, but the researchers note that even higher pressures are currently used in engineering processes such as chip manufacturing today, so it's something achievable outside of a specialized lab.

If confirmed by other researchers, this would be a huge breakthrough in creating devices that don't waste energy on heat when producing a current.

Ideally this could one day be used to create more efficient computers; faster, frictionless maglev trains; superior X-ray technology; and even more powerful nuclear fusion reactors.

"With this material, the dawn of ambient superconductivity and applied technologies has arrived," the team said in a press release.

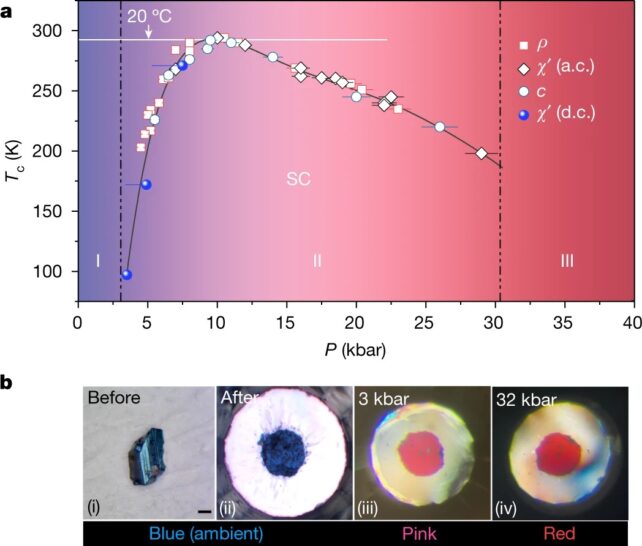

The researchers have dubbed the material 'reddmatter' due to the material dramatically changing from blue to pink as it becomes superconductive, and later to red as it becomes a non-superconductive metal.

Before you get too excited, keep in mind that for now this is just one team of researchers sharing their own observations. The data have been published in the prestigious journal Nature, and is sure to draw plenty of debate. There's already plenty of healthy skepticism out there in the physics world.

One of the main concerns is that this same group of researchers published claims of a similar superconductor breakthrough at room temperature, back in 2020. This claim was later retracted by Nature due to issues with reproducibility and questions over the data.

Superconductivity is such a big deal because, usually, when electricity flows through wires – say, going from a power plant to your home, or through the internal circuitry of your smart phone – it's met with friction. This resistance results in energy being lost as heat.

Back in 1911, researchers identified that there were some materials that lost this resistance under extreme cold and high pressure.

In these extreme conditions, the quantum behaviors of electrons inside superconductors strengthen to allow them to form what are known as Cooper pairs, allowing them to travel through the material with perfect efficiency.

Superconductivity is relatively easy to spot as it also results in a material expelling magnetic flux fields.

But getting materials to superconduct at temperatures and pressure levels that are efficient and practical has been incredibly challenging, and something physicists have spent decades working on.

The team from the University of Rochester claim they've now been able to get close to this with reddmatter.

To create the material, researchers developed a gas mixture that was made up of 99 percent hydrogen and 1 percent nitrogen. Left in a chamber with lutetium for a few days at 200 degrees Celsius, the components reacted to form a striking blue compound.

The team then placed the material inside a diamond anvil which is used to put materials under extreme pressure.

As pressure increased the material underwent a "marked visual transformation", going from blue to pink as it became superconductive – something the team confirmed by measuring both the magnetic fields around the material and its electrical conductivity.

As the pressure continued to build the material turned bright red, passing through its superconductive phase and into a non-superconductive metallic state.

Reddmatter displayed superconductivity at around 21 degrees Celsius (70 Fahreneheit), when compressed to a pressure of 145,000 pounds per square inch.

This is still roughly 10,000 times the pressure of Earth's atmosphere, so it'd still require the right kinds of structures and equipment to make practical use of it. It's unlikely to be giving your phone superpowers any time soon.

But it's a significantly lower pressure than other candidates for room temperature superconductors, which require millions of times atmospheric pressure.

One of the big issues now is that the researchers aren't entirely sure of the exact structure of reddmatter. That makes it hard to understand how it's becoming superconductive.

There are indications it may be achieving superconductivity through a different mechanism to other superconductors, physicists ChangQing Jin and David Ceperley, who weren't involved in the research, note in an accompanying Nature New and Views article.

"[The] structural model … suggests that there is relatively little hydrogen present in the authors' samples compared with in similar superconducting compounds," they write.

"Further research will be needed to confirm that [the] material is a high-temperature superconductor, and then to understand whether this state is driven by vibration-induced Cooper pairs – or by an unconventional mechanism that is yet to be uncovered."

Dias admits there is still a lot to be understood about how reddmatter achieves superconductivity. But he remains optimistic reddmatter is an important first step, even if it doesn't end up being the best superconductor out there.

"In day-to-day life we have many different metals we use for different applications, so we will also need different kinds of superconducting materials," said Dias.

"A pathway to superconducting consumer electronics, energy transfer lines, transportation, and significant improvements of magnetic confinement for fusion are now a reality," he added.

"We believe we are now at the modern superconducting era."

The research has been published in Nature.