Think of the dinosaur era and you probably think about huge beasts rampaging across the landscape.

But plenty of smaller creatures existed, too - like this newly discovered prehistoric baby bird, smaller than your little finger.

When it was alive around 127 million years ago, the bird would've been less than five centimetres (1.97 inches) tall, weighing in at 8.5 grams (0.3 ounces). Think the size of an American cockroach, and you're on the right lines.

The chick comes from a group of prehistoric birds called Enantiornithes, and the scientists behind the new analysis think it can teach us more about the very earliest days of avian evolution - including how the first birds came to live alongside dinosaurs millions of years ago.

Enantiornithes sized up against a cockroach. (Raúl Martín)

Enantiornithes sized up against a cockroach. (Raúl Martín)

"The evolutionary diversification of birds has resulted in a wide range of hatchling developmental strategies and important differences in their growth rates," says one of the researchers, Fabien Knoll from the University of Manchester in the UK.

"By analysing bone development we can look at a whole host of evolutionary traits."

What makes the finding particularly special is that palaeontologists have recovered almost the full skeleton from the fossil, and that the bird died shortly after it hatched – giving us an insight into the still-developing bone structure of the little critter.

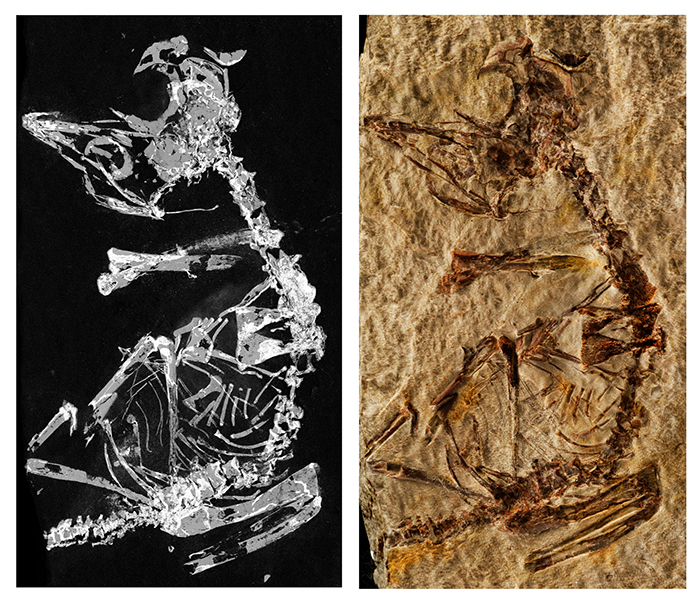

This being one of the smallest known avian fossils ever recovered from the Mesozoic Era (250-65 million years ago), researchers used a special technique called synchrotron microtomography to map the bone structure in precise detail.

It uses powerful X-ray beams to effectively see inside rocks without having to open them up first. With the right computer software, those scans can be turned into 3D models.

Phosphorous mapping and photo of fossi. (University of Manchester)

Phosphorous mapping and photo of fossi. (University of Manchester)

One of the key findings from the research was that the bird's sternum (breastplate bone) hadn't yet developed into solid bone from cartilage, so it wouldn't have been able to fly yet.

Whether that means the bird would've been over-reliant on its parents for much of its early life is difficult to determine, say the researchers. The fossil study did reveal that this particular group of birds may have developed in more diverse ways than had been previously thought.

The bird was largely featherless too, the scans suggest, though again the researchers say it's not easy to be sure.

Ultimately the question remains on whether these sorts of birds would've been confined to their nest or able to wander around independently as they grew up. Every finding like this one, however, fills in a bit more of the picture.

With fossils such as this one so rare, peering so far into the past isn't easy, but modern techniques like synchrotron microtomography are helping.

"New technologies are offering palaeontologists unprecedented capacities to investigate provocative fossils," says Knoll. "Here we made the most of state-of-the-art facilities worldwide including three different synchrotrons in France, the UK and the United States."

Links between dinosaurs and the birds of the time are of huge interest to researchers, partly because the smallest of these birds were able to survive the infamous meteor smash and help repopulate the world in a post-dino age.

This is why the birds of today give us an evolutionary link back to the prehistoric ages - and this tiny little prehistoric bird could be an important part of that… besides looking like a cute little creature too.

"It is amazing to realise how many of the features we see among living birds had already been developed more than 100 million years ago," says one of the team, Luis Chiappe from the LA Museum of Natural History.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.