Not all DNA is the same, and science has long held that not all kinds of DNA are passed down from both your mother and your father. But it looks like the time has come to rewrite the textbooks.

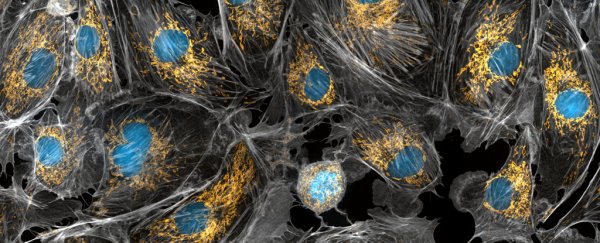

While most of our DNA resides within the nucleus of the cell, some of our genetic code is stored inside mitochondria, the so-called 'powerhouse of the cell'. The conventional view is this mitochondrial DNA (or mtDNA) is only inherited from mothers, but new evidence suggests that's not the case at all.

A new study led by geneticist Taosheng Huang from the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Centre shows human mitochondrial DNA can be paternally inherited, in a landmark case that started with the treatment of a sick four-year-old boy.

The child, who was showing signs of fatigue, muscle pain, and other symptoms, was evaluated by doctors, and tested to see if he had a mitochondrial disorder.

When Huang ran the tests – and then ran them again to be sure – he couldn't make sense of the results that came back.

"That's impossible," he told NOVA Next.

The reason Huang was so shocked was because the boy's results showed a mix – called a heteroplasmy – in his mitochondrial DNA, which was made up of more then just maternal contributions.

While there's evidence of paternal mtDNA transmission in other species, the existence of the phenomenon in humans has been debated, but has never before been demonstrated like this.

"This upends entire fields based on genetics," ecologist Trevor Branch from the University of Washington, who wasn't involved with the research, tweeted about the discovery.

When the boy's sisters showed evidence of the same heteroplasmy, Huang and fellow researchers analysed the mtDNA of the children's mother, which also showed the same mix.

This led the team to analyse the mother's parents' mtDNA, ultimately finding that the mother's mtDNA came from a roughly 60/40 split respectively from her mother and father.

"Our results suggest that, although the central dogma of maternal inheritance of mtDNA remains valid, there are some exceptional cases where paternal mtDNA could be passed to the offspring," the authors explain in their paper.

But while these cases might be exceptional, they're not necessarily as rare as scientists might have thought.

In all, the researchers identified three unrelated multi-generation families that showed a high level of mtDNA heteroplasmy – ranging from 24 to 76 percent – across 17 separate individuals.

Prior to this, two separate case reports occurring early in the century had suggested biparental mtDNA transmission may be possible, but for 16 years no other evidence came forward.

Now, we know those results weren't isolated, and as sequencing technology becomes progressively more advanced, it gives us a better tool for understanding just what's going on here and how common paternal mtDNA transmission really is.

"This is a really groundbreaking discovery," biologist Xinnan Wang from Stanford University, who wasn't involved in the research, told NOVA Next.

"It could open up an entirely new field… and change how we look for the cause of [certain mitochondrial] diseases."

The researchers say that the strength of the former view – that only maternal transmission was possible – could have meant many instances of biparental transmission before now were overlooked as technical errors.

Be that as it may, they suggest their "clear and provocative" evidence should now initiate a broader assessment of the mtDNA possibilities, despite maternal transmission remaining the norm.

"Clearly, these results will need to be brought in agreement with the fact that maternal inheritance remains absolutely dominant on an evolutionary timescale and that occasional paternal transmission events seem to have left no detectable mark on the human genetic record," the team writes.

"Still, this remains an unprecedented opportunity in the field."

The findings are reported in PNAS.