Even if you're enjoying gloriously fast broadband at home wherever you live in the world, you're still going to be a long, long way behind the new record for data transmission: an incredible 1.02 petabits per second.

That's a million gigabits shifted down a line every single second. The record was set by a team at the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT) in Japan, transmitting the data over 51.7 kilometers (32 miles).

To put it another way, there's enough bandwidth here to transmit not just one 8K video feed, or a hundred or a thousand 8K video feeds, but 10 million 8K video feeds simultaneously. That's a lot of Netflix.

One of the exciting aspects of the new data transmission speed record is that researchers achieved it using an optical fiber network not dissimilar to those currently used for internet infrastructure. This, the researchers say, should make future upgrades towards this sort of speed easier.

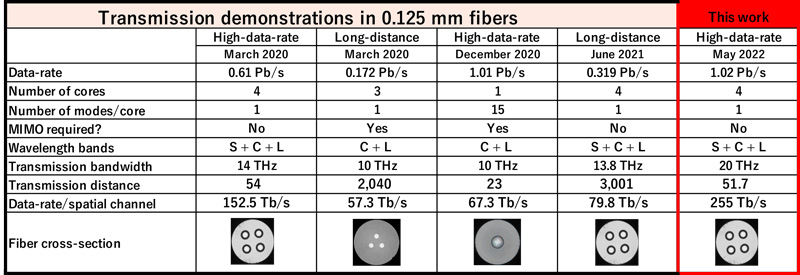

Only a year ago, researchers from the same institute were getting maximum speeds around a third of what they've now managed, showing the rapid development of the technology.

The experiment used 0.125 mm diameter multi-core fiber (MCF), with wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) acting as the magic ingredient: This technology means signals of different wavelengths are sent simultaneously through the line. A total of 801 parallel wavelength channels were packed into the same line.

Another innovation was to use four cores instead of the standard one, essentially quadrupling the routes for data to take, all while keeping the cable the same size as a standard optical fiber line. Researchers also applied various other optimization, signal boosting, and decoding technologies.

A table comparing data transmission experiments. (NICT)

A table comparing data transmission experiments. (NICT)

In specialized experiments like this one, there's usually a balance between distance and speed – high speeds are harder to maintain over longer distances. The team plans to continue to improve both transmission speed and transmission distance in their future research.

While the same group of researchers hit the petabit milestone back in December 2020, they used more complicated technology that required extra work to encode and decode the signals. The system used in this case is easier to implement in actual physical networks and more like the infrastructure that already exists.

With 5G also continuing to roll out across the world, the signs are good for a future of gadgets hooked up to an always-on, high-speed internet connection – although the number of devices that need to get online continues to rise rapidly.

"Beyond 5G, an explosive increase of data traffic from new information and communication services is expected and it is therefore crucial to demonstrate how new fibers can meet this demand," according to a NICT press release.

"It is hoped that this result will help the realization of new communication systems able to support new bandwidth hungry services."

The research was presented in May at the International Conference on Laser and Electro-Optics (CLEO) 2022.