Around 1,500 years ago, perhaps around 450 CE, unknown raiders stormed the small, prosperous village of Sandby borg on the shore of Öland island, and slaughtered the inhabitants, leaving the bodies where they fell.

Now, archaeologists in Sweden have stumbled upon this grisly mystery. With less than 7 percent of the site excavated, the research team, led by archaeologists Clara Alfsdotter, Ludvig Papmehl-Dufay and Helena Victor, has already found the remains of at least 26 bodies.

It doesn't look like much now - just a grassy green mound ringed by an oval of rock, but it was once a thriving settlement.

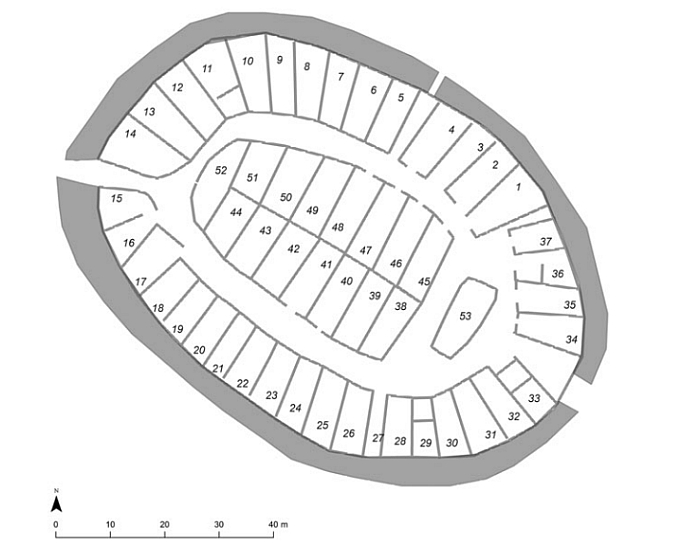

The village was inside a ringfort not far from the shoreline, containing 50 or so homes circled by walls that stood 4 to 5 metres (13 to 16 feet) high. Around 200 to 250 people would have lived there.

At the time, the European Migration Period was underway, and it was an unstable, tumultuous time; but who killed the villagers and why remains a mystery nonetheless.

The layout of Sandby borg. (Alfsdotter et al./Antiquity)

The layout of Sandby borg. (Alfsdotter et al./Antiquity)

The dig team has only excavated three of the homes - but what they have found is deeply moving. The bodies exhibit signs of blunt force trauma, or supine positions that indicate they died suddenly, or were unconscious prior to death.

The remains of a five-year-old child and an infant just a few months old were also found, and two skeletons were partially charred - in a manner that indicates that the soft tissue was still present. Possibly they fell into fires, or a fire was started - either accidentally or on purpose.

One skeleton (pictured at the top of this article), of an adolescent no older than 15, had its feet resting on the abdomen of another skeleton, as though the young person had tripped, or fallen backwards over another body, never to get up again.

Bodies were also found in the streets, along with the remains of dogs and livestock, which could have starved to death, or also been killed in the attack. One house contained nine sets of human remains.

Historically, the people of the area cremated their dead. It all points to absolute carnage.

"You don't find people lying around in houses," Victor told the BBC. "[People] don't do it today, and didn't do it then."

Five gilt brooches recovered from Sandby borg. (Alfsdotter et al./Antiquity)

Five gilt brooches recovered from Sandby borg. (Alfsdotter et al./Antiquity)

Even more curious: the site is abundant with treasure. Gold coins, glass beads, gilded brooches, rings and silver pendants of high quality were found scattered. Everything except weapons.

Whoever sacked the Sandby borg village didn't loot the site - except, perhaps, for potential weapons, which may have been taken as a trophy or tribute to the gods. It's unknown whether the residents defended themselves - but it seems like they didn't, the researchers said.

"Damage resembling common battle injuries, such as parry fractures or facial trauma, both typically produced when facing an opponent, has so far not been identified," they wrote in their paper.

"This pattern leads us to conclude that the perpetrators comprised a large number of people, striking simultaneously in several houses, and that several of the victims were not in a position to defend themselves."

Although the island at the time was populated by around 15 other ringfort villages, no one ever visited the site to loot the homes or inter the bodies. They remained where they fell, the village abandoned, until the roofs collapsed and the macabre scene was buried by time.

Snadby borg prior to the excavations. (Kalmar County Museum)

Snadby borg prior to the excavations. (Kalmar County Museum)

Even to this day, whispers remain, although there's no record, either written or oral, of the massacre. Local people, the researchers said, warned them to stay away from the site, vaguely inferring it was dangerous.

"I do find it most likely that the event was remembered and that it triggered strong taboos connected to the site, possibly brought on through oral history for centuries," Papmehl-Dufay said.

The local Kalmar County Museum is featuring an exhibition of the excavation, and work on the site continues.

A paper detailing the team's work so far can be read in the journal Antiquity.