Half a billion years ago, the ocean floor was thought to be completely void of life, an ancient dead zone without the necessary oxygen for survival.

Thanks to a lucky new discovery, scientists are now second-guessing that assumption. Hiding in a slab of northern Canada's ancient sea floor, geologists have uncovered a 'superhighway' of prehistoric worm tunnels.

These fossilised tunnels date back to the Cambrian period - 270 million years before the first dinosaurs - and they suggest that even the deepest seabeds held more life, and oxygen, than we once thought.

The discovery was made by Brian Pratt, a geologist and palaeontologist from the University of Saskatchewan, 35 years after he first collected the sedimentary rocks from the Mackenzie Mountains in northwest Canada.

"Serendipity is a common aspect to my kind of research," says Pratt.

"I found these unusual rocks quite by accident all those years ago. On a hunch I prepared a bunch of samples and when I enhanced the images I was genuinely surprised by what I found."

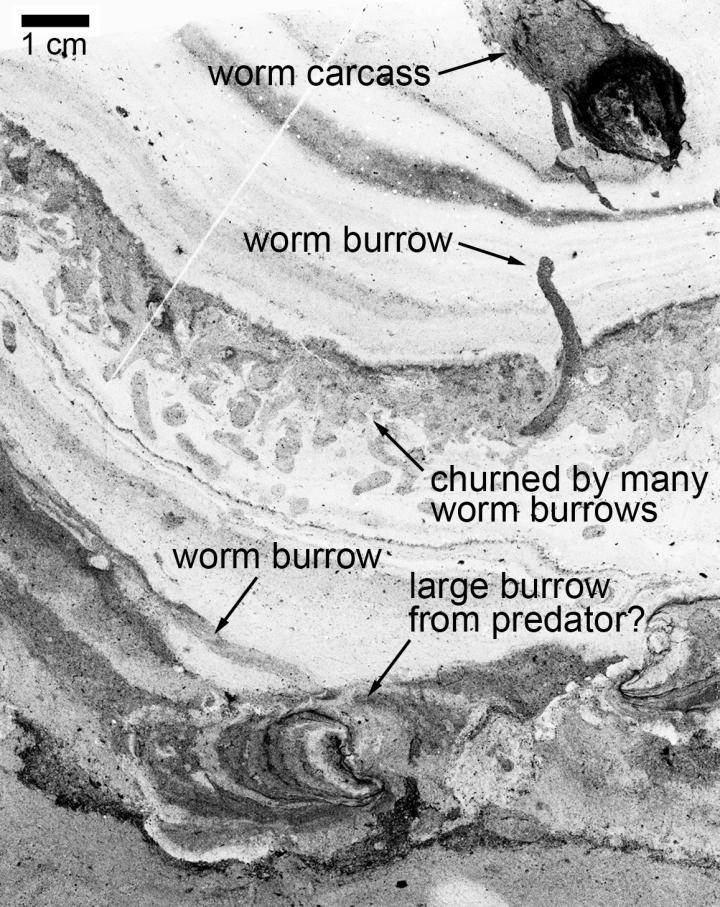

The burrows where these ancient worms once used to roam were not visible until Pratt used a flatbed scanner and image editing to bring them to life.

There, in the slices of rock, was a nice surprise: an abundance of exceptionally well-defined burrows, criss-crossing each other in every which way.

These tunnels ranged from 0.5 to 15 millimetres (0.02 to 0.6 inches), which suggests there was quite a bit of diversity in worm life at this time and in this unexpected place.

Some of the prehistoric worms, for instance, are estimated at no more than a millimetre, while others are thought to be as long as a finger.

(Brian Pratt, University of Saskatchewan)

(Brian Pratt, University of Saskatchewan)

The authors think the smaller tunnels were made by polychaetes, a simple creature also known as a bristle worm. Meanwhile, the larger burrows probably belonged to predators, who liked to attack unsuspecting arthropods and other surface-dwelling worms from their hiding spot.

The Cambrian period is known for its explosion of life, with multicellular organisms developing and spreading right across the globe. The Burgess shale, also located in northern Canada, is famous for its remarkably preserved Cambrian fossils.

Scientists thought these fossils had been so well preserved because they'd fallen to the bottom of the sea where there was little oxygen to speed up their decay, and also fewer animals around who'd eat the evidence.

If the new research is right and there was, in fact, life in the seafloor, we may need to rethink some of our assumptions about ancient oceans and the continental shelves they sit upon.

"This has a lot of implications which will now need to be investigated, not just in Cambrian shales but in younger rocks as well," says Pratt.

"People should try the same technique to see if it reveals signs of life in their samples."

This study has been published in Geology.