The most important set of genetic instructions we all get comes from our DNA, passed down through generations. But the environment we live in can make genetic changes, too.

Last year, researchers discovered that these kinds of environmental genetic changes can be passed down for a whopping 14 generations in an animal – the largest span ever observed in a creature, in this case being a dynasty of C. elegans nematodes (roundworms).

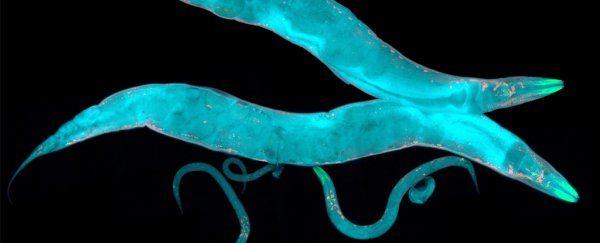

To study how long the environment can leave a mark on genetic expression, a team led by scientists from the European Molecular Biology Organisation (EMBO) in Spain took genetically engineered nematode worms that carry a transgene for a fluorescent protein. When activated, this gene made the worms glow under ultraviolet light.

Then, they switched things up for the nematodes by changing the temperature of their containers. When the team kept nematodes at 20° Celsius (68° F), they measured low activity of the transgene - which meant the worms hardly glowed at all.

But by moving the worms to a warmer climate of 25° C (77° F), they suddenly lit up like little wormy Christmas trees, which meant the fluorescence gene had become much more active.

Their tropical vacation didn't last long, however. The worms were moved back to cooler temperatures to see what would happen to the activity of the fluorescence gene.

Surprisingly, they continued to glow brightly, suggesting they were retaining an 'environmental memory' of the warmer climate – and that the transgene was still highly active.

Furthermore, that memory was passed onto their offspring for seven brightly-glowing generations, none of whom had experienced the warmer temperatures. The baby worms inherited this epigenetic change through both eggs and sperm.

The team pushed the results even further - when they kept five generations of nematodes at 25° C (77° F) and then banished their offspring to colder temperatures, the worms continued to have higher transgene activity for an unprecedented 14 generations.

That's the longest scientists have ever observed the passing-down of an environmentally induced genetic change. Usually, environmental changes to genetic expression only last a few generations.

"We don't know exactly why this happens, but it might be a form of biological forward-planning," said one of the team, Adam Klosin from EMBO and Pompeu Fabra University, Spain.

"Worms are very short-lived, so perhaps they are transmitting memories of past conditions to help their descendants predict what their environment might be like in the future," added co-researcher Tanya Vavouri from the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute in Spain.

There's a reason why scientists turn to C. elegans as a model organism - after all, those 14 generations would only take roughly 50 days to develop, but can still give us important clues on how environmental genetic change is passed down in other animals, including humans.

There are many examples of this phenomenon in worms and mice, but the study of environmental epigenetic inheritance in humans is a hotly debated topic, and there's still a lot we don't know.

"Inherited effects in humans are difficult to measure due to the long generation times and difficulty with accurate record keeping," stated one recent review of epigenetic inheritance.

But some research suggests that events in our lives can indeed affect the development of our children and perhaps even grandchildren - all without changing the DNA.

For example, studies have shown that both the children and grandchildren of women who survived the Dutch famine of 1944-45 were found to have increased glucose intolerance in adulthood.

Other researchers have found that the descendants of Holocaust survivors have lower levels of the hormone cortisol, which helps your body bounce back after trauma.

The 2017 study on nematodes is an important step towards understanding more about our own epigenetic inheritance - especially because it serves as a remarkable demonstration of how long-lasting these inter-generational effects may be.

The findings were published in Science.

A version of this article was first published in April 2017.