It's thought that humans, unlike other primates, have evolved certain muscles unique to us. But now those muscles have been found in other apes - and this challenges our core perceptions about human evolution.

According to anatomist Rui Diogo of Howard University in the US, a large part of the human narrative revolves around our "special" place in nature, which can lead to unverifiable explanations for our evolution.

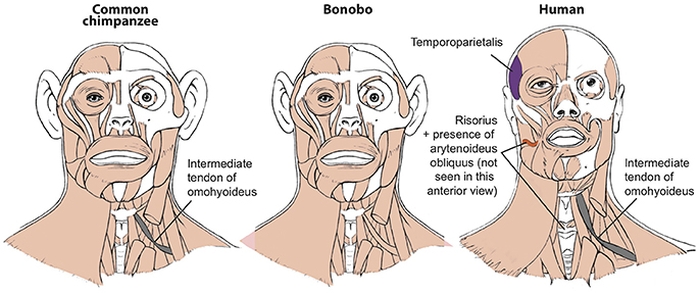

This includes focussing on specific muscles that only humans are thought to have, namely for walking upright, using tools, communicating vocally, and for specific facial expressions.

"Our detailed analysis shows that in fact, every muscle that has long-been accepted as 'uniquely human' and providing 'crucial singular functional adaptations' for our bipedalism, tool use and vocal and facial communications is actually present in the same or similar form in bonobos and other apes, such as common chimpanzees and gorillas," says Diogo.

"This study contradicts key dogmas about human evolution and our distinct place on the 'ladder of nature."

Without detailed knowledge of the anatomy of our closest primate relatives, the claims about things like special bipedal muscles actually have no legs. So Diogo specifically searched other primates for seven muscles thought to have evolved only in humans.

A large challenge lay in finding ape specimens to dissect, as well as historical anatomical studies that focussed only on a few details. Part of Diogo's methodology was to find all the available literature on ape anatomy and carefully examine it for hints of the muscles.

Along with colleagues at the University of Antwerp, he also conducted anatomical studies on several bonobos - our closest relatives, along with chimps - that had died of natural causes.

Differences in head muscles between chimps, bonobos and humans. (Rui Diogo)

Differences in head muscles between chimps, bonobos and humans. (Rui Diogo)

He found all seven of these "human-specific" muscles in bonobos, chimps and gorillas - and they took either a very similar or exactly the same shape.

For instance, the muscle thought to be associated with walking upright and absent in hominoid apes, the fibularis tertius, was found in 3 of the 7 bonobos dissected, looking exactly like it normally appears in humans.

He also found muscles thought to be associated with vocal speech - the arytenoideus obliquus in the larynx and and the facial muscle risorius - in some chimps and gorillas.

These findings demonstrate that the evolution of human soft-tissue may not be as "special" as previously thought, and we'll need more research to figure out how we evolved differently from other primates.

"We need a more thorough examination of why these muscles are present in apes and, in some cases, in just part of a population within a certain species," Diogo said.

"Are these muscles essential for the apes that have them, as adaptationist evolutionary scientists would argue? Or are they evolutionary neutral features related to how their bodies develop, or simply by-products of other features?"

He also added that most theories of human evolution that mark humans as anatomically distinct from apes tend to be "unverifiable 'just-so stories'".

"The real evidence shows we are not so different overall. This study highlights that a thorough knowledge of ape anatomy is necessary for a better understanding of our own bodies and evolutionary history."

The study has been published in Frontiers in Ecology & Evolution.