We know that depression is linked to variations in the way our brains are wired, but new research suggests that people who are going through a depressive episode actually see the world around them differently.

And the team behind the study hopes that a better understanding of how visual information is processed in the brains of people with depression could help to inform our treatment approaches in the future.

The researchers wanted to analyze how the cerebral cortex – responsible for receiving messages from the five senses – handled an optical illusion, testing it out with 111 people who were experiencing major depressive episodes and 29 people who weren't.

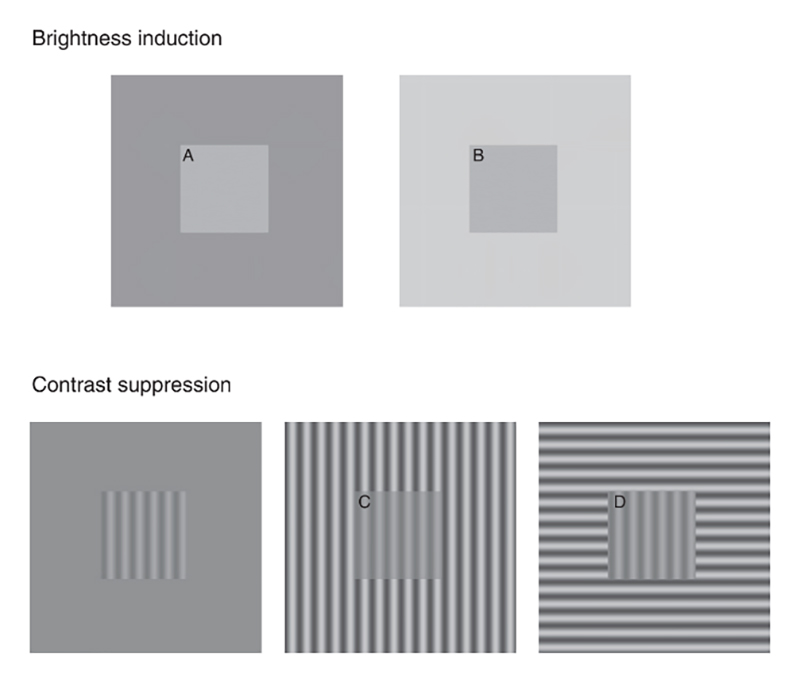

The optical test used in the study – patches A and B and patches C and D are the same. (Salmela et al, J. Psychiatry Neurosci., 2021)

The optical test used in the study – patches A and B and patches C and D are the same. (Salmela et al, J. Psychiatry Neurosci., 2021)

The trick, which you can see above, puts patches of identical brightness and contrast on different backgrounds, and the variation in context is usually enough to fool the brain into thinking the central sections themselves are different.

"What came as a surprise was that depressed patients perceived the contrast of the images shown differently from non-depressed individuals," says psychologist Viljami Salmela, from the University of Helsinki in Finland.

The brains of those with depression were more likely to be taken in by the contrast part of the illusion, while there was little difference between the groups when it came to the brightness part of the trick.

It's possible that a weaker contrast signal gets beamed from the retina to the cortex in people with depression, though further research is going to be needed to work out exactly what is going on – it's possible that changes are happening in the information sent back by the eyes, or in the ways it's processed in the brain, or both.

What makes the optical illusion such a good test is that it challenges the eyes and the brain to make sense of what's being seen, and to balance out brightness and contrast. It could also be telling that the contrast test involves rotation, while the brightness one doesn't.

"Because contrast suppression is orientation-specific and relies on cortical processing, our results suggest that people experiencing a major depressive episode have normal retinal processing but altered cortical contrast normalization," write the researchers in their paper.

"Furthermore, contrast suppression was similarly reduced in patients with unipolar MDD [major depressive disorder], bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder."

This isn't the first time researchers have found a curious link between depression and visual processing in the brain, though it does give experts more insight into the neural mechanisms of people with a major depressive disorder.

There are some limitations to the study: the team used self-reporting from the participants rather than brain scans to assess what they were seeing. It's also possible that medication for depression could be influencing some of the changes in visual processing.

However, similar results have been seen in people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, suggesting this sort of shift in how the eyes and the brain perceive the outside world could be common across several psychological disorders.

"It would be beneficial to assess and further develop the usability of perception tests, as both research methods and potential ways of identifying disturbances of information processing in patients," says Salmela.

The research has been published in the Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience.