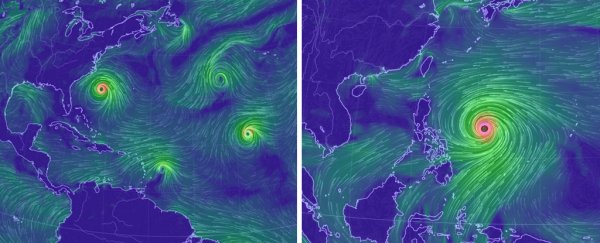

The Northern Hemisphere is facing an onslaught of hurricanes and typhoons, seemingly overnight. With three storms spinning in the North Atlantic - Hurricane Florence one of them - the tropics have exploded to life at the peak of the annual season.

At the same time, in the tropical Pacific, Super Typhoon Mangkhut is the most intense tropical cyclone in the world, packing 170 miles per hour (273 kilometres per hour) winds.

Why the remarkable uptick in activity? In the Atlantic, in particular, it's all thanks to a sudden alignment of the two things that fuel hurricanes: energy and wind.

If the winds aloft in the atmosphere are too strong, they can shear apart a developing storm. It's ironic but true - calm winds are needed to brew a hurricane. The amount of shear in the Atlantic has reached its seasonal minimum, kindling any fledgling storm and fostering its growth.

What also changed in the past two weeks is how much instability - or "juice" - storms had to work with. Until two weeks ago, we were well below average. Then all of a sudden, a switch flipped, and the results were explosive.

Category 4 Hurricane Florence is on a crash course with the coast of the Carolinas. As steering currents in the atmosphere slacken this weekend, concern is growing that Florence may stall - prolonging its barrage and producing catastrophic rainfall.

Florence has company in the Atlantic. Helene is a Category 1 west of Cabo Verde, boasting 90 miles per hour (144 kilometres per hour) winds. While the storm is impressive on satellite, it looks likely to remain over the open ocean. The storm will probably become swept up in the jet stream over the weekend, possibly dousing parts of Europe with some heavy rainfall toward the middle of next week.

Isaac is also out there spinning around. The tropical storm will buffet the Lesser Antilles with 60 miles per hour (96 kilometres per hour) winds before passing well south of Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean.

Overwhelmed yet? But wait - there's more.

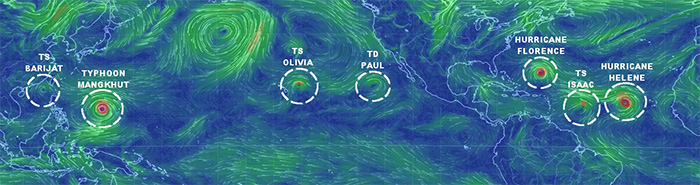

Above: Wind speed and streamlines around the global tropics highlighting what are now six active tropical cyclones. Tropical Depression Paul was downgraded to a remnant low. (The Washington Post/earth.nullschool.net)

We're also watching not one, but two additional systems in the Atlantic. A disturbance posted just offshore of the Yucatan Peninsula is likely to become a tropical depression by the weekend.

The National Weather Service may dispatch an Air Force reconnaissance plane to probe the system Wednesday. The National Hurricane Center is advising residents along the coasts of Texas and Louisiana to monitor the system.

An additional wave of low pressure several hundred miles southwest of the Azores may also develop tropical or subtropical characteristics in the next couple of days, but it remains no immediate threat to any land.

If the other two systems in the Atlantic develop into tropical storms, there could be five cyclones simultaneously. That's only ever happened once - between 10 and 12 September, 1971.

Into the Pacific, Super Typhoon Mangkhut is producing winds sustained to 170 miles per hour (274 kilometres per hour) and enormous waves as it treks about 200 miles (322 km) west of Guam.

The monster storm is expected to clip the northern Philippines on Friday as a the equivalent of a strong Category 5 hurricane.

That's not the only tempest lurking off the coast of China. Tropical Storm Barijat will pass south of Hong Kong Wednesday.

Hong Kong will also have a close call with Mangkhut, which is predicted to pass near the city of 7 million over the weekend, probably as a low-end Category 1 equivalent.

Hawaii is dealing with its own Pacific threat. Tropical Storm Olivia is deluging the archipelago with up to 15 inches (38 centimetres) of rain in spots.

Barely two weeks ago, Hawaii set a state record for all-time storm total rainfall - an astonishing 52.02 inches (132.1 centimetres) from Hurricane Lane. With the tropical paradise under the gun again, it's no surprise that climate change may favor more Hawaii storms in the years ahead.

There is one additional system to watch west of Mexico, but it looks as if it will remain tame.

So combining all of this tropical storm action together, how does it compare with what's normal?

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy, or ACE, is a metric that combines the duration and intensity of storms. Across the Northern Hemisphere, the year is at 159 percent of average for the date.

The largest contribution to the anomaly comes from the East Pacific (245 percent of average), followed by the West Pacific (124 percent of average) - the Atlantic and Indian oceans are both slightly above their climatological averages.

This surge of activity in the middle of September is not a big surprise, though. If we look at the timeline of historical activity in each of the major basins, this time of year is no stranger to action:

- The West Pacific can see storm any month of the year but has a broad peak from July through October.

- The East Pacific hurricane season is not as long (mid-May through the end of November) and has a broad peak in August and September.

- The Atlantic season is the shortest of them all (June through November) and has much more narrow peak during the first half of September.

So right now, tropical storm activity is typically elevated in all of these basins.

But even at this active time, this year is even more busy than normal. Capital Weather Gang contributor Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane researcher at Colorado State University, maintains a website for tracking this sort of activity.

Using the data available there, when we can break things down by basin, we see that every ocean basin is featuring near normal to above normal tropical activity in 2018:

- The Atlantic was above average for the entire season up until August 21. Then things slowed down, and it reached the normal level of activity Tuesday.

- The East and Central Pacific have been well above average since June (with the exception of a brief nudge below average at the end of July).

- The West Pacific has wavered around average through its season but is currently high.

- The North Indian Ocean has been above average since late May, though its normal amount of activity is quite low anyway.

What does this all mean in terms of climate? The answer is unclear. There is research to suggest that the number of storms that develop will not change significantly as a result of climate change.

Instead, there is a likelihood that those that develop could become increasingly strong. Regardless, one thing is clear: What's happening in the tropics worldwide right now is out of the ordinary.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.