Proteins linked to Alzheimer's disease could be passed between patients on surgical tools, new research suggests. Though the number of cases identified so far is very small, it may prompt a rethink in how these tools get sterilised and used in the future.

There's no indication yet that Alzheimer's has been caused by proteins being carried in this way, but researchers found eight cases of patients with the rare brain bleeding disorder cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) who had also had brain surgery at a younger age.

Considering none of the eight people had a genetic disposition to CAA, it's possible that the earlier surgery carried amyloid proteins into their brains – sticky proteins which have been linked to triggering both CAA and Alzheimer's disease.

"We have found new evidence that amyloid beta pathology may be transmissible," says senior researcher Sebastian Brandner, from University College London (UCL) in the UK.

"This does not mean that Alzheimer's disease can be transmitted, as we did not find any significant amount of pathological tau protein which is the other hallmark protein of Alzheimer's disease."

While scientists still aren't sure about how Alzheimer's gets started, the build up of amyloid beta and tau proteins in the brain – leading to a breakdown in its normal functions – seems to be one of the main hallmarks of the disease.

It's possible that amyloid protein build-ups from one brain operation got passed to other patients on contaminated surgical instruments – though it's important to note that in all these eight cases, the childhood surgery dates from before the most recent review of sterilisation procedures.

In other words, the problem might have already been fixed, but the scientists behind the new study don't want to take any chances.

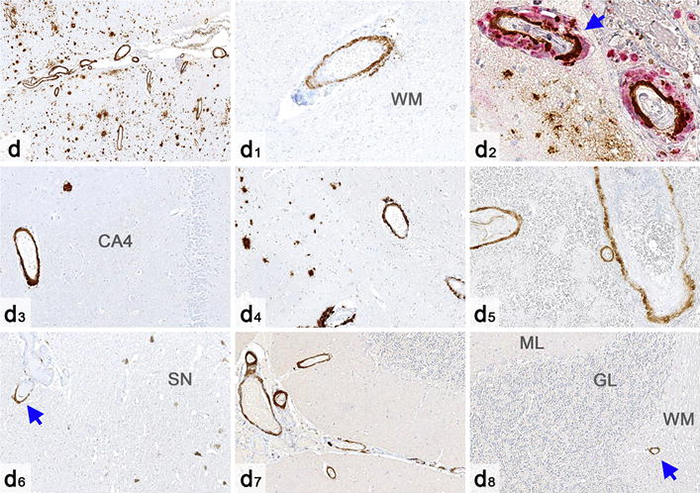

Evidence of amyloid protein build-up. (UCL)

Evidence of amyloid protein build-up. (UCL)

"Our findings relate to neurosurgical procedures done a long time ago," says Brandner. "Nevertheless, the possibility of pathological protein transmission, while rare, should factor into reviews of sterilisation and safety practices for surgical procedures."

The team found four people with CAA who had also been operated on as youngsters, then dug back into historical records to find four more who matched the pattern.

And the research was prompted by previous concerns over the transmission of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, another brain disease, through proteins called prions stuck to surgical tools. In fact, that discovery is what prompted the most recent update to sterilisation standards.

The problem is that amyloid proteins are very resistant to the usual methods of boiling and drying instruments, and exposing them to formaldehyde. Having tools that are only used once in certain situations could be the answer, suggest the researchers.

To be clear, none of these eight patients developed Alzheimer's, but there's a chance the brain could be more vulnerable to it if amyloid proteins are getting swapped in this way.

Now the researchers want to see further studies on the potential for proteins to travel like this – with the number of neurosurgical operations on older people on the rise, and build-ups of these proteins increasing with age, we need to know the facts.

"There are several reasonable alternative explanations for our findings that we cannot yet rule out," says one of the team, Simon Mead from UCL. "Further research is required to clarify things. A large epidemiological study would be particularly useful."

The findings have been published in Acta Neuropathologica.