Jupiter's moon Ganymede is a pretty special chunk of rock.

It's the largest and most massive moon in the Solar System. It's the only Solar System moon that generates its own magnetic field. It has the most liquid water of any Solar System body. And now, scientists have discovered, it may have the largest impact structure ever identified.

Astronomers have found that the tectonic troughs known as furrows, thought to be the oldest geological features on Ganymede, form a series of concentric rings up to 7,800 kilometres (4,847 miles) across, as though something had slammed into the moon.

This has yet to be confirmed with more observations, but if the rings were indeed formed by an impact, it will vastly outstrip all other confirmed impact structures in the Solar System.

Ganymede's furrows are troughs with sharp, raised edges, and it's long been considered that they are the result of large impacts early in Ganymede's history, when its lithosphere was relatively thin and weak. But a reanalysis of Ganymede data led by planetologist Naoyuki Hirata of the Kobe University Graduate School of Science tells a slightly different story.

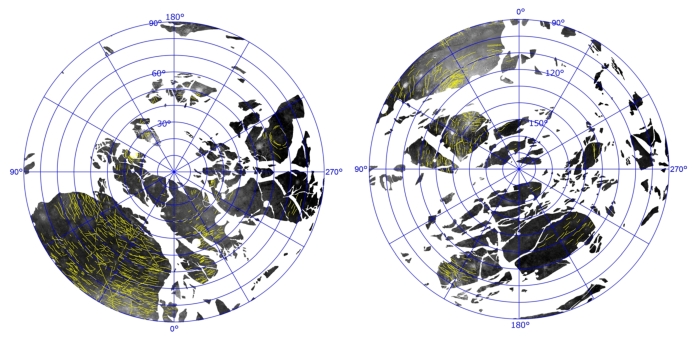

To try to better understand the history of Ganymede, Hirata and his colleagues took a closer look at images obtained by spacecraft - both Voyager probes, which flew by Jupiter in 1979, and the Galileo Jupiter orbiter, which studied the planet and its satellites from 1995 to 2003.

These images show that Ganymede has a complex geological history. The moon is divided into two types of terrain - the Dark Terrain and the Bright Terrain. The Bright Terrain is lighter in colour, and relatively lacking in craters - suggesting it is much younger than the heavily scarred Dark Terrain.

(NASA/Hirata et al.)

(NASA/Hirata et al.)

This older terrain is pocked and cratered. And those craters were made on top of previous scarring - the furrows that can be found throughout most of the Dark Terrain.

The team carefully catalogued all the furrows, mapping them across the surface of Ganymede. They found that almost all of these structures, rather than being haphazardly arranged around many impact points, were concentrically focussed on a single point.

Furthermore, the troughs wrapped around the moon, spanning up to 7,800 kilometres. Ganymede's diameter is 5,268 kilometres (3,273 miles) - so that's a pretty enormous ripple, to put it mildly.

(Hirata et al., Icarus, 2020)

(Hirata et al., Icarus, 2020)

The next step in the research was to determine what could have caused such a structure. The team ran simulations of various scenarios, and found that the most likely culprit was an asteroid 150 kilometres (93 miles) across, slamming into the moon at a velocity of around 20 kilometres per second (12 miles per second).

This would have taken place during the Late Heavy Bombardment, around 4 billion years ago, when Ganymede was quite young. During this period, the moon is thought to have taken an absolute cometary pummelling due to gravitational focusing by Jupiter - so a giant impact is certainly plausible.

In addition, a similar structure can be found nearby. On Jupiter's moon Callisto, the Valhalla crater is a multi-ring impact crater with a diameter of up to 3,800 kilometres (2,360 miles), thought to be between 2 and 4 billion years old.

The Valhalla crater is also the current record-holder for biggest impact structure in the Solar System, followed by the Utopia Planitia on Mars, an impact basin (not a multi-ring structure) 3,300 kilometres (2,050 miles) across.

The new discovery awaits confirmation, but we may not have to wait long to find out. If the furrows were caused by a giant impact, there should be a gravitational anomaly at the impact site, as seen in other large impact structures such as the South Pole-Aitken Basin on the Moon.

Now that we know to look for it, perhaps Jupiter probe Juno could be used to search for this anomaly. In addition, the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) probe will be launching in 2022, the first dedicated mission to study Jupiter's moons. It, even more than Juno, could illuminate the cause of these mysterious structures.

The research has been published in Icarus.