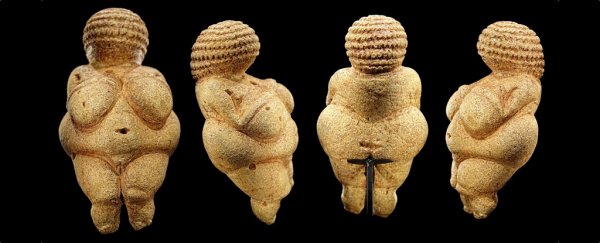

They rank among some of the oldest known art in the world. Strange statuettes of female figures dating back to the Late Stone Age, many with heavily rounded breasts, buttocks, thighs, hips, and stomachs.

These iconic, stylised depictions of women from the Upper Palaeolithic – often called Venus figurines, in a loose reference to the Roman goddess of beauty – have been found scattered across Europe and Eurasia.

Over 200 of these mysterious figurines have been uncovered, dated between 38,000 to 14,000 years ago, with most of those recovered from about 26,000-21,000 years ago.

While there is much academic debate about what the Venus figurines represented in the eyes of their ancient carvers, many researchers have interpreted the statues' voluptuous characteristics as symbols of fertility, sexuality, beauty, and motherhood.

Others have also noted, however, that the enlarged bodies offer a very realistic depiction of what human obesity looks like. Obesity is a grave problem for people in the 21st century, although why it would have been on the minds of our ancient ancestors 30,000 years ago isn't entirely clear.

"Some of the earliest art in the world are these mysterious figurines of overweight women from the time of hunter gatherers in Ice Age Europe, where you would not expect to see obesity at all," says medical researcher Richard Johnson from the University of Colorado.

In a new study, Johnson and fellow researchers offer an alternative explanation for mystery of the figurines' exaggerated physiques: the bodies are not swollen as symbols of sex, they say, but as symbols of survival.

The researchers analysed dozens of the figures with obese features from various chapters in the period, measuring the statues' waist-to-hip and waist-to-shoulder ratios. When those measurements are compared to where the statues were found – specifically, noting distances to ancient glaciers that existed – an interesting connection was found.

Many of the Venus figurines were carved during an extreme window of climate change called the Last Glacial Maximum, in which temperatures plummeted and ice masses expanded throughout many parts of the world.

Amidst the hardship, the statues were carved; it's possible, the researchers say, that their shapely forms were created in a sort-of response to the creeping cold.

"During this period, humans faced advancing glaciers and falling temperatures that led to nutritional stress, regional extinctions, and a reduction in the population," the researchers explain in the study, noting the strange relationship they found.

"Figurines are less obese as distance from the glaciers increases… Specifically, the body size proportions were largest when the glaciers were advancing, whereas obesity decreased when the climate warmed and glaciers retreated."

In the team's hypothesis, the full-figured Venuses existed as a symbol of survival in the face of an unrelenting winter, exemplifying the virtues of over-nourished women, whose larger, fattier bodies could better withstand the harsh, freezing conditions.

"We propose they conveyed ideals of body size for young women, and especially those who lived in proximity to glaciers," Johnson says.

The researchers contend that obese women would have been better at carrying pregnancies during the Last Glacial Maximum, and also at breastfeeding.

"The figurine would represent a desired likeness of the woman in which the image had power to bring about a healthier mother and child, spanning conception, a precarious pregnancy, childbirth, and nursing," the authors write.

"Increased fat would provide both a source of energy during gestation through the weaning of a baby as well as much needed insulation."

It's a fascinating argument, although it's worth noting that not everybody in the archaeology community has welcomed their findings.

Still, if the researchers are right, these iconic statuettes – many worn down, as if they had been handled as heirlooms over successive generations – could have played a greater symbolic role than ever known, in shepherding humanity through one of its bleakest climatic challenges.

"During this period, the figurines emerged as an ideological tool to help improve fertility and survival of the mother and newborns," the researchers conclude.

"The aesthetics of art thus had a significant function in emphasising health and survival to accommodate increasingly austere climatic conditions."

The findings are reported in Obesity.