Forget the romance of camping on the Moon – an unimpeded rain of radiation would make even short stays an express trip to Cancer City. One way to protect potential lunar residents from high doses of cosmic rays would be to stick their base underground.

Researchers have now confirmed the perfect hidey-hole for just such a cosy home would be inside a lava tube in the Moon's Marius Hills region. The view isn't anything to write home about, but the health benefits would be worth it!

Scientists from Purdue University in the US and Japan's space agency – or JAXA – made clever use of radar data and information on the patterns of density across the Moon's surface to map out a suspect depression, establishing it as a candidate site for future Moon villages.

Lava tubes on the Moon are pretty much the same as those here on Earth.

Molten rock flowing over the lunar surface quickly cools solid on the outside while staying runny on the inside. Once the internal stream of lava slows to a trickle, hollow passages can often form.

It's been a while since the Moon was geologically active, but its surface could still be riddled with such tubes and caves left over from its youth several billion years ago.

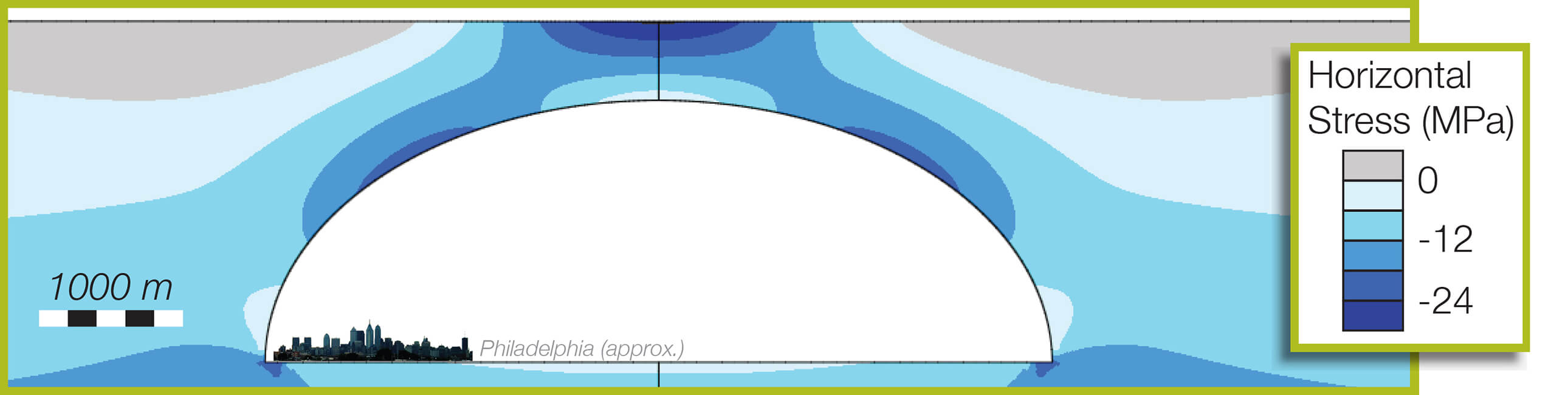

These wouldn't necessarily be small cracks, either. Thanks to the relatively low lunar gravity, some could theoretically be large enough to form a solid igneous roof over a base the size of a city.

Purdue University/David Blair

Purdue University/David Blair

Most of this is speculation, though. Deep holes seen on the Moon's surface could easily be sections of collapsed tubes, but until now there have been few details on how far underground such caves run.

"It's important to know where and how big lunar lava tubes are if we're ever going to construct a lunar base," says Junichi Haruyama from JAXA.

A region on the near side of the Moon called Marius Hills looks like the bubbled surface of a cooking pancake, making it a good spot to look for lava tubes.

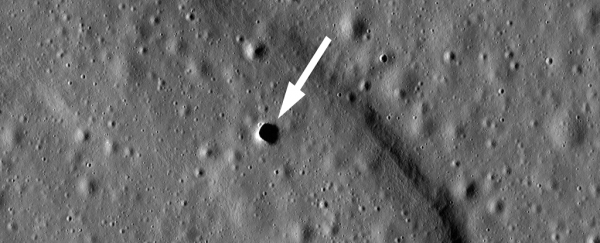

One window into the underworld discovered in the area by the Japanese Selenological and Engineering Explorer (SELENE) seven years ago has been screaming out for further study.

This giant 'rabbit hole' was later confirmed by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, but few details on the deeper parts of its structure were gathered.

Now the researchers have used SELENE's data in combination with information provided by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission, using gravitational patterns in the area to determine the rock's density, and therefore the likelihood of hollows.

"They knew about the skylight in the Marius Hills, but they didn't have any idea how far that underground cavity might have gone," says Jay Melosh, a GRAIL co-investigator and researcher from Purdue University.

"Our group at Purdue used the gravity data over that area to infer that the opening was part of a larger system. By using this complimentary technique of radar, they were able to figure out how deep and high the cavities are."

To be detectable, the Marius Hills lava tube would need to be a few kilometres (a mile or two) in length, and at least a kilometre (about two thirds of a mile) in height and width.

While that isn't enough details to start modelling for giant curtains, it does promise a refuge to explore for founding a sizeable colony.

The longest an astronaut has spent on the Moon's surface is about three days. To make a lunar base at all viable for longer periods, residents would need protection to cope with an unfettered shower of accelerated plasma particles and high energy electromagnetic radiation.

A roof of rock would go a long way to stopping a significant percentage of those DNA-destroying rays.

It would also help provide access to geology that would otherwise require some digging to reach.

"We might get new types of rock samples, heat flow data, and lunar quake observation data," says Haruyama.

Renewed interest in recent years encouraging private enterprises to find ways to set off into space has turned Moon shots into feasible goals, that might see us set foot on the lunar surface again in the next decade or so.

An actual Moon village could be on the horizon. Marius Hills might not be the most picturesque destination in space, but living in a Moon cave isn't so bad when you consider the hazards of the alternative.

This research was published in Geophysical Research Letters.