America under President Trump might not own Greenland (yet), but decisions made by his administration will help determine the ice-covered island's long-term fate and ours.

US emissions of greenhouse gases, as well as emissions from other countries, have tipped the balance to make Greenland a major contributor to global sea-level rise.

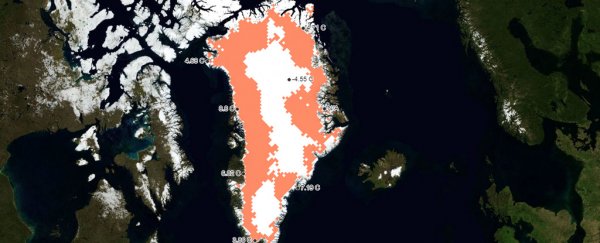

It's no secret that the Greenland ice sheet is in trouble. This melt season, which is wrapping up, has brought the most significant ice loss, and related sea-level increase, since the record melt year of 2012.

Much of the ice melted in a one-week period when the island was in the throes of a heat wave that had moved in from Europe.

According to Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the University of Colorado, this year Greenland will add about 1 millimeter to global sea levels through glacial outflow and melt runoff, which translates to about 360 gigatons of water entering the North Atlantic.

In addition, the injection of cold freshwater is disrupting ocean circulation, specifically causing a slowdown in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, which could alter weather patterns and fisheries.

Greenland ice melt, triggered by increased amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, has worsened coastal flooding in the United States and elsewhere.

Changes to the island's gravitational pull as a result of shedding so much ice mean that some areas are being affected more than others. In Miami, where coastal flooding on sunny days has become a regular hazard, Greenland ice melt has greater effects than in other vulnerable coastal cities, such as Boston.

"Greenland really holds the fate of Miami in its hands in terms of how much sea level rise is going to come out of there," Scambos said.

According to Ben Strauss, chief executive and chief scientist at Climate Central, a climate science and journalism organization, "100,000 Americans live per [each] vertical inch above high tide line, averaged over the first 10 feet. Every bit of sea level rise counts."

Richard Alley, an expert on ice sheets at Penn State University, put the gravitational effects of Greenland ice loss into perspective in an email: "The ice sheet is so massive that its gravity affects the sea level - the ocean is attracted to Greenland's ice enough to raise the sea level around Greenland."

"If the ice melts, the mass is spread out into the world ocean very rapidly, but then the extra water that was held near Greenland also spreads out," Alley said.

A complete meltdown is up to us

Studies have shown that during past periods when Earth was about as warm as it is today, the entire Greenland ice sheet was lost, raising global sea levels by about 23 feet.

With the world on course to experience about 7.2 degrees (4 Celsius) of warming above preindustrial levels by 2100, it's possible we'll pass a critical threshold beyond which there's no preventing a complete or near-complete disappearance of the ice sheet.

"The critical threshold temperature is poorly known, but is not too many degrees above modern, [and] almost surely can be reached by human-caused warming if we continue to emit carbon dioxide rapidly from fossil-fuel burning and other processes," Alley said.

Already, Greenland's rate of ice loss has increased sixfold since the 1980s, going from 41 gigatons per year during the 1990s to 286 gigatons per year during the period from 2010 to 2018.

The rate and extent of surface melting across the Greenland ice sheet can quickly change with even a small amount of warming. "Raising the temperature by a degree or two more in summer means that a huge area of the ice sheet will begin to melt," Scambos said.

A recent study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that in a high-emissions scenario, Greenland could contribute up to two feet of global sea level rise by 2100.

Other studies have shown that if significant emissions cuts are made in the next decade or two, the total amount of sea level rise from Greenland, as well as Antarctica and other sources, could still be limited.

But time is running out, regardless of who "owns" Greenland.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.