Archaeologists have unearthed fragments of several human skulls from a dig site in southeast Turkey with some rather unusual groove patterns scratched into their surface.

The incisions and perforations appear to be intentional, making them the first evidence of a funerary ritual in that part of the world, and possibly evidence of an ancient cult.

Situated a stone's throw from the Syrian border, the Palaeolithic site of Göbekli Tepe already has a reputation as a game-changer for archaeologists providing the oldest evidence of prehistoric worship.

Carved stones surrounding a number of massive T-shaped pillars mark out what archaeologists can only conclude to be a temple, one that predates Stone Henge by 6,000 years.

The site's foundation around 9,000 BCE puts it right on the cusp of the dawn of agriculture, challenging hypotheses claiming it was our ability to grow crops and domesticate livestock that allowed complex society and organised religion to develop.

In spite of early suspicions the site was a medieval graveyard, there have never been any signs of bodies being formally buried at the site.

But since excavation began in the mid-1990s, archaeologists have still found scattered fragments of human remains among rubble that also contained animal bones and stone artefacts.

Oddly, of the nearly 700 human bone pieces discovered so far, 408 have come from the skull. Even weirder still, 40 of these show cut marks consistent with being de-fleshed after death, while two out of the seven neck vertebrae found indicate decapitation.

In this latest research, anthropologists have closely analysed three of the skull fragments and determined the marks on them are more than just nicks and scratches – they are intentional carvings.

"The carvings consist of many deep cuts – somebody clearly did it intentionally," Julia Gresky from the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin told Andrew Curry at Science magazine.

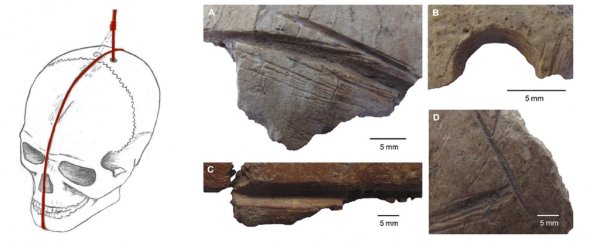

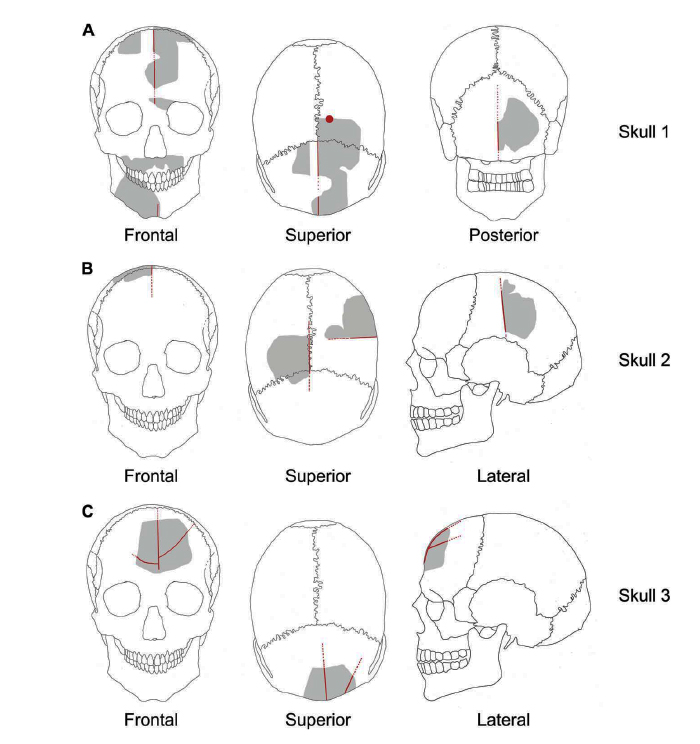

Long, deep cut marks on seven fragments from three skulls show signs of a sharp stone tool being dragged repeatedly in a line, distinguishing it from the single and scattered scratches left when flesh is removed from bone.

On one skull, the line runs down the centre of the forehead and onto the back of the head, while a second skull has a similar line with a pair of grooves branching out at angles. In one skull fragment, a portion of a hole has been drilled through the bone.

German Archaeological Institute

German Archaeological Institute

While they were clearly made on purpose, their roughness suggests it wasn't about aesthetics.

"They're deep incisions, but not nicely done. Someone wanted to make a cut, but not in a decorative way," Gresky explained.

Given the position of the skull with the hole, it's possible the incisions could be to help hold or hang the skulls in place.

The bones had barely any collagen left in them, a protein that provides carbon useful for dating. That made it a challenge to nail down their exact age, but based on their position the individuals could have lived anywhere between 10,000 and 11,500 years ago.

Göbekli Tepe isn't short on complex stone carvings, with one making the news a few months ago for being a possible recording of a prehistoric comet impact.

Other carvings have seemed strangely preoccupied with heads, with examples of figurines having their heads broken off, or in the case of a figurine found near the skulls, holding what seems to be a head in its hands.

Looking at the evidence together, it's not hard to imagine gatherings of semi-nomadic communities in the area proudly dangling the skulls of their enemies from strings, or even worshipping the heads of their loved ones tied in place along a wall.

"In archaeological discourse, the term skull cult is used relatively broadly, describing not only the intentional modification of human skulls but also their deposition in selected contexts," the researchers write in their report.

Without examples showing how of the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe and its surrounds buried their dead, it's hard to say with much certainty what the skull carvings mean. One of the pieces was found in a concentration of ochre, a material that has been associated with Palaeolithic burials in other contexts.

Hopefully future excavations will unearth more clues on what went on at Göbekli Tepe 11,000 years ago.

This research was published in Science Advances.