It's the most populous city in Western Asia, and it's sinking into the ground at an alarming rate.

Tehran, the capital of Iran and home to some 15 million people in total across its greater urban footprint, is a victim of dramatic subsidence, new research reveals, which is causing the region to sink by more than 25 centimetres (almost 10 inches) annually in some parts.

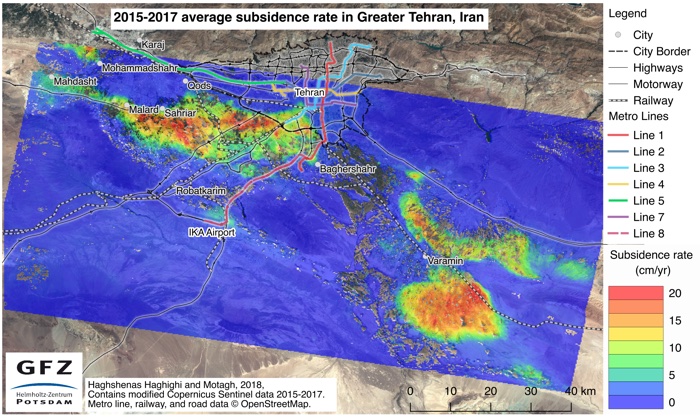

Using satellite data, researchers at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam analysed the extent of subsidence in the Tehran region between 2003 and 2017.

Thanks to a technique called Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR), which can detect extremely subtle changes in ground deformation over time, the team identified three distinct areas where the ground is sinking by more than 25 centimetres per year.

In areas of more moderate subsidence, like the land in the immediate vicinity of Tehran international airport, the sinking is still considerable, at about 5 centimetres annually.

(Haghshenas Haghighi and Motagh 2018/GFZ)

(Haghshenas Haghighi and Motagh 2018/GFZ)

What's the cause of this widespread instability? A history of accelerated influx and the attendant overuse of natural resources.

"In recent decades, rapid population growth combined with urban and industrial development have increased the need for water supplies in the Tehran Plain," the authors explain in their paper.

"As a result of extensive groundwater depletion, the plain has been undergoing rapid land subsidence."

This subsidence in Tehran has been the focus of much prior research, but the latest data put the sinking in greater context.

"These are amongst some of the highest current rates of subsidence in the world," engineer Roberto Tomás from the University of Alicante in Spain, who wasn't involved in the study, told Nature.

According to the researchers, Tehran's booming economy and population since the 1960s resulted in over 32,000 wells exploiting the region's aquifers in 2012 (there were less than 4,000 in 1968).

This, together with the construction of numerous dams in the region for the benefit of agriculture, has helped deplete the aquifers, leading not only to water shortages, but these dramatic subsidence effects.

"The average groundwater level in Tehran decreased by approximately 12 metres (39.3 ft) from 1984 to 2011," the authors explain.

"Earth fissures, damage to buildings, shifts on the ground, and cracks in walls are evidence of groundwater-induced compaction that have been observed in the Tehran Plain."

When aquifers deform like they have in Iran, the compression can sometimes be irreversible, but to avoid the worst effects, the researchers state it's up to the region's decision-makers to steer water use in a more sound direction.

"Science and research could support Iranian administrations and governments to revise their water management policy for a sustainable development," says one of the team, geodesy researcher Mahdi Motagh.

If not, a hazardous situation could potentially become even more unstable in the future.

"Unless effective groundwater management is implemented, ongoing subsidence in Tehran is expected to cause further damage to infrastructure," the authors explain, "particularly in the regions of high displacement gradients in the urban areas of Tehran and near IKA airport."

The findings are reported in Remote Sensing of Environment.