California has been caught in the midst of a fiery assault fueled by historically powerful winds, humidity levels stuck in the single digits, and the effects of long-term climate change.

Fierce, fast-moving wildfires exploded up and down the state during October, prompting utilities to shut off power to millions and forcing hundreds of thousands to evacuate.

But while tens of thousands fled the flames, there are a handful of researchers who have driven towards them. Scientists with San Jose State University's Fire Weather Research Laboratory have been deploying to the blazes, taking advantage of the dire fire weather to test an experimental Doppler radar capable of peering into wildfire smoke plumes at unprecedented resolution.

Researchers hope the system will yield new insights into the inner structure and evolution of the most dangerous blazes. This could lead to better tools for tracking and forecasting fires, thereby reducing damage and casualties.

"This system is unique," says Craig Clements, the director of the Fire Weather Research Laboratory who's led deployments of the new radar over the last few weeks.

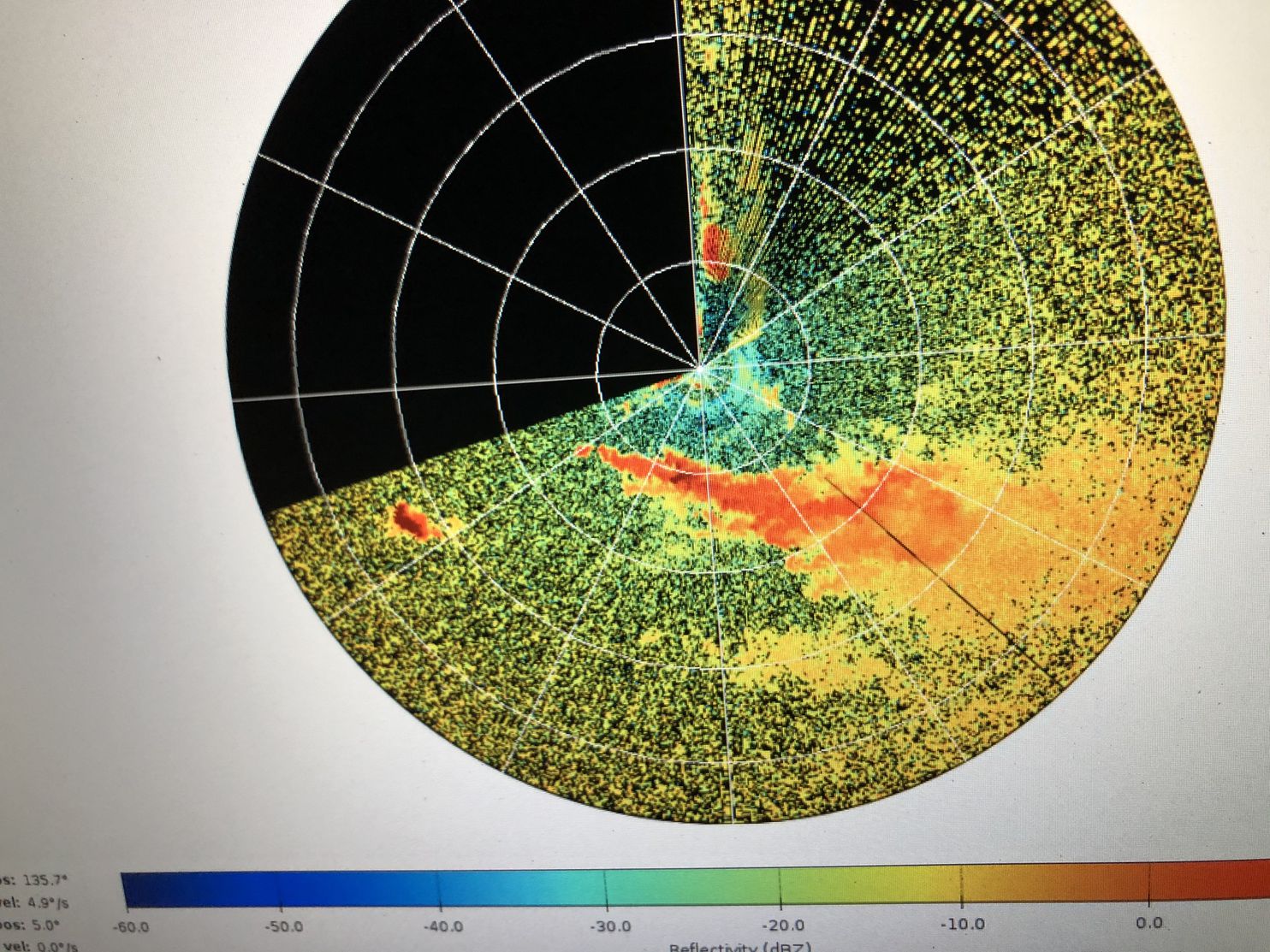

Doppler radars emit pulses of microwave energy into the air where it bounces off particles, whether that's raindrops, snow, insects, or ash. The reflections the radar picks up provide information on the size and motion of those particles, which help scientists paint a picture of the weather event.

Fire researchers have used mobile Doppler radar rigs to study wildfires before, and they've also taken advantage of fixed radar stations operated by the National Weather Service to track large blazes.

But they've never had an instrument quite so well-suited to peering inside the plume of an active fire and capturing its evolution in real-time. While weather radars typically use a set of frequencies with wavelengths of about 10 centimeters -the so-called S-band - SJSU's new radar relies on the Ka band, a set of of millimeter-wavelength frequencies that are better able to detect the fine, ashy particles present in wildfire plumes.

The radar also scans faster and at a higher resolution than most radar systems, as well as the LiDAR units fire researchers have deployed in the past, meaning it can produce more detailed smoke plume snapshots more often.

And because the radar is mounted on a truck, the scientists working with the Fire Weather Research Laboratory can bring it out to an active fire and start collecting information within minutes of arriving on the scene.

"It's night and day," says Neil Lareau, a fire weather researcher at the University of Nevada, Reno who helped put together a proposal for this radar system while he was a professor at SJSU.

To visualize how much of a leap in resolution the new tool represents, Lareau made the analogy to images of Pluto captured before and after NASA's 2015 New Horizons flyby mission.

Originally, SJSU scientists were going to deploy the radar for the first time to study a large, controlled burn that the US Forest Service had planned to set in southern Utah at the end of the month or in early November.

But when fires started erupting across California in early October, Clements and his team mobilized. So far, they've sent their radar out to the field three times: Once to look at the Briceburg Fire that flared up near Yosemite National Park toward the beginning of the month, and twice to study the Kincade Fire that roared to life in Northern California's Sonoma County last week.

In an overnight survey of the Kincade Fire, Clements said the team captured some "amazing details" with the new radar, including information on the wind field and turbulence within the plume. The ferocious winds that large wildfires produce not only help them spread, but can spin up dramatic fire whirls.

Currently, weather models are unable to forecast them, and they can cause fires to behave erratically, overtaking fire crews.

The system also captured a great deal of information on the size and shape of plume particles, including what the researchers believe to be embers that were buoyed aloft via updrafts. A key way that some large wildfires grow is by hurling hot embers hundreds or even thousands of feet ahead of the fire front.

But until now, scientists' ability to track this process, called "ember casting," has been very limited.

A Ka Band radar image showing a smoke plume (orange and red area). (SJSU Fire Weather Research Laboratory)

A Ka Band radar image showing a smoke plume (orange and red area). (SJSU Fire Weather Research Laboratory)

"The radar has the potential to see where these embers are going up and where they're coming down," Lareau says. "This has the potential to map things out in real time."

Ultimately, Clements and his colleagues hope the data they're collecting will help front-line responders tackle the large, intense, and hard-to-predict wildfires that are becoming more frequent out West as landscapes warm up and dry out.

New insights into processes like ember casting and the formation of fire-induced winds could be fed into wildfire models, improving their ability to predict where a fire will jump next.

With further refinement, similar radars might be made available to fire management teams one day, providing them with detailed real-time reconnaissance information as they're fighting a blaze.

"In the same way you can see where a thunderstorm will be in an hour, we might (one day) be able to do that for fires," Lareau says.

With fire danger remaining high until the rainy season finally arrives in California, scientists with the fire lab may have a busy few weeks ahead.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.