The hardening of our ageing arteries has been a tricky process to pin down, but new research might finally have the answer. It might even take us closer to treatments that limit this blood vessel condition, which can increase the risk of heart attack, dementia and stroke.

While it's already known that calcium deposits are the reason why arteries stiffen with age, it doesn't tell us why that build-up accumulates. According to this latest study, the process could be triggered by a molecule called poly(ADP-Ribose) or PAR.

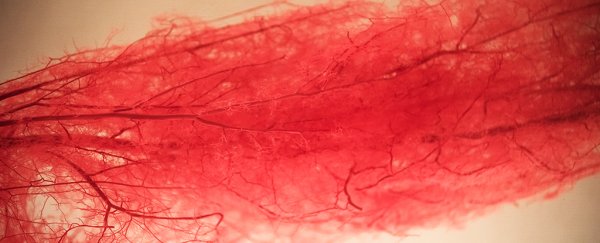

PAR is a repair protein that gets produced when cells or cell DNA gets damaged; as it binds very strongly with calcium, it starts mopping up calcium into larger droplets. Those droplets then solidify, sticking to artery walls and reducing their elasticity, the study reveals.

"This hardening, or biomineralisation, is essential for the production of bone, but in arteries it underlies a lot of cardiovascular disease and other diseases associated with ageing like dementia," says cell biologist Cathy Shanahan from King's College London in the UK.

"We wanted to find out what triggers the formation of calcium phosphate crystals, and why it seems to be concentrated around the collagen and elastin which makes up much of the artery wall."

The release of PAR was spotted in various cell cultures, including human blood vessel samples, using a technique called Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, which is able to analyse samples down to the molecular level.

The implication of a protein produced by cell damage makes a lot of sense, given that ageing, high blood pressure and smoking are all known to increase the risk of stiffening arteries. And what they have in common is the DNA damage they are known to cause; so if the researchers are right, the damage ends up calling on PAR to fix it, in turn hardening the arteries as a byproduct.

"Up until now we haven't known what controls this process and therefore how to treat it," says biochemist Melinda Duer from the University of Cambridge in the UK.

"We never would have predicted that it was caused by PAR. It was initially an accidental discovery, but we followed it up – and it's led to a potential therapy."

That potential therapy could centre around an existing antibiotic called minocycline. It's already used to treat acne, and because it's been through the necessary safety testing, the whole process of adapting it for preventing arterial stiffening could be sped up.

Through some short-term initial tests on rats, the team was able to demonstrate the effectiveness of minocycline in inhibiting the production of PAR. Clinical trials could happen within the next 18 months, according to the researchers.

It's worthwhile to note that this part of the research was provided for and funded by Cycle Pharmceuticals, a company whose work explicitly includes finding ways to repurpose drugs that already exist on the market.

While we might not be able to stop artery stiffening completely as a natural consequence of ageing – and healthy lifestyle habits still play an important role – minocycline or a similar drug does appear to have the potential to lower the risk of health problems associated with these calcium deposits.

That said, antibiotic therapy doesn't come without its own host of side-effects and costs, so time will tell whether this approach will truly lead to a practical solution. Still, the more we learn about the intricacies of our cardiovascular health, the better we can help our ageing population.

The research has been published in Cell Reports.