Lab-grown livers could be saving lives much sooner than previously thought, thanks to new research, by providing some key functions of the organ without being a complete replacement.

That would mean these artificially engineered organs could prop up a failing liver or help those waiting for a transplant to hold out until a human liver became available.

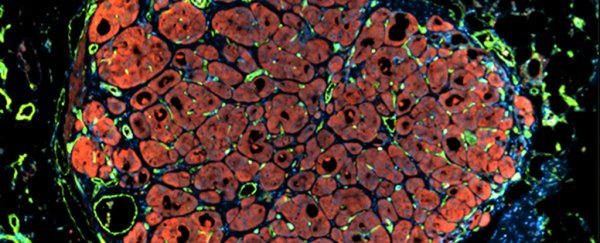

A team drawn from several US institutions created small subunits of engineered liver tissue, that when implanted into mice with damaged livers were able to expand 50-fold and cover some of the functions normally carried out by the liver.

"Our goal is that one day we could use this technology to increase the number of transplants that are done for patients, which right now is very limited," says senior researcher Sangeeta Bhatia from MIT.

Bhatia and her colleagues built a biodegradable tissue scaffold designed to encourage cell growth, then embedded three types of cells in the scaffold before implanting it in the mice. Usually, scientists create scaffolds the size of the organs they're trying to emulate.

In other words, the researchers created mini or baby livers designed to plug the gaps left by a full-sized but damaged liver.

The cells used were hepatocytes, which carry out the key functions of the liver, fibroblasts, which provide structure for tissue, and endothelial cells, the building blocks of blood vessels.

Once implanted, the mix of cells get regenerative signals from the surrounding environment, producing blood vessels and more hepatocytes.

A healthy human liver has about 100 billion hepatocytes, and the researchers think an engineered miniature organ would need about 10 to 30 percent of that number to be useful to the body.

By the time the implants had taken hold, scientists found signs that all the key liver functions – regulating metabolism, detoxifying the body, producing bile – were working to some extent.

And that's a hopeful result for people with chronic liver problems or who are waiting for a transplant.

"What if a patient is only missing one of the liver's 500 functions?" lead researcher Kelly Stevens told Kristen V. Brown at Gizmodo.

"Maybe a baby liver would be enough. The liver is second only in complexity to the brain. But if you could even add back the ability of one function it might be enough to save someone."

The idea of creating baby organs artificially isn't a completely new one, although this research does introduce a new technique for growing them: Sangeeta Bhatia and her team have been working on the problem since 2011.

What helps researchers in this case is that the liver is one of very few organs that can regenerate itself, prompting the growth shown here. Even so, 17,000 people in the US alone are currently waiting for a liver transplant.

In this study the researchers used cells from human livers that were found to be unsuitable for transplants, but further down the line the tissue could be generated from liver cells taken from the patient or grown from stem cells in the lab.

Dave Gobel, CEO of tissue engineering non-profit the Methuselah Foundation, wasn't involved in this study but told Gizmodo that the research showed promise even though it is still in its "very, very early stages".

"The cool thing about the liver is that it does regenerate itself, so if you could augment a diseased liver by 10 percent or more, you have a shot at keeping someone alive until a transplant liver becomes available," he said.

"Or in best case, the liver might get enough of a boost to turn the corner and regenerate itself."

The research has been published in Science Translational Medicine.