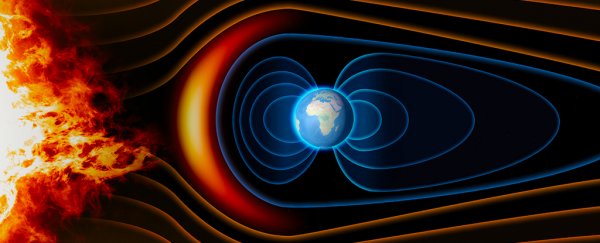

We know that Earth's magnetic field is always shifting in its direction and its strength. Just how quickly these changes are happening is of great interest, considering this planetary feature keeps us all protected from violent cosmic radiation.

Now, a new analysis of ancient lava flows in eastern Scotland – filling in some crucial blanks in our magnetic field history – has backed up previous research pointing to a 200-million-year cycle during which the field weakens and then strengthens again.

The team also used the magnetic history they found buried in the geological record to double-check other measurements made over the last few decades, and to chart a history of Earth's magnetic field going back some 500 million years.

"Our findings, when considered alongside the existing datasets, support the existence of an approximately 200-million-year long cycle in the strength of the Earth's magnetic field related to deep Earth processes," says paleomagnetist Louise Hawkins, from the University of Liverpool in the UK.

"As almost all of our evidence for processes within the Earth's interior is being constantly destroyed by plate tectonics, the preservation of this signal for deep inside the Earth is exceedingly valuable as one of the few constraints we have."

Thermal and microwave paleomagnetic analysis techniques were used on rock samples from the ancient lava flows, with the alignment of mineral crystals inside them revealing the state of Earth's magnetic field at the time they were originally formed.

The team discovered that between 332 and 416 million years ago, there was a dip in the magnetic field that matches up with another one from 120 million years ago. During the earlier period, now called the Mid-Palaeozoic Dipole low (MPDL), the field surrounding Earth was around a quarter of the strength that it is today.

Those dates match up with the 200-million-year cycle, and give experts some important new insights into how the magnetic field was behaving more than 300 million years ago, in the lead up to a notable Superchron – the name given to an extended period of time when the field stays stable.

"This comprehensive magnetic analysis of the Strathmore and Kinghorn lava flows was key for filling in the period leading up the Kiman Superchron, a period where the geomagnetic poles are stable and do not flip for about 50 million years," says Hawkins.

If this cycle holds true, and the magnetic pole flips or reversals tend to happen every 200,000-300,000 years, we're actually due for another one – much to the concern of scientists, who aren't sure what the effect will be on all the technology and gadgets we obviously didn't have last time it happened.

The more we know about the history of Earth's magnetic field in general, the better we can predict what it's going to do next. If our force field against space radiation starts to develop problems, we need to know about it as early as possible.

There was another bonus finding to the research too: it has previously been thought that flips in the magnetic field's orientation happen when the field is weaker, and this is another hypothesis that the new data backs up.

"Our findings also provide further support that a weak magnetic field is associated with pole reversals, while the field is generally strong during a Superchron, which is important as it has proved nearly impossible to improve the reversal record prior to around 300 million years ago," says Hawkins.

The research has been published in PNAS.