Scientists have just found a new distinction between the brains of the two sexes: age-related changes to the brain occur more slowly in women than in men.

The jury is still out on whether cognitive differences between men and women are created by nature or nurture - or to what extent they even exist - but we do know that average structural differences between the sexes are a real thing.

This latest research now indicates that female brains, on average, appear to be about three years more youthful than the brains of males of the same age when it comes to brain metabolism.

This difference could be why women tend to stay mentally sharp for longer than men, the researchers said.

"We're just starting to understand how various sex-related factors might affect the trajectory of brain ageing and how that might influence the vulnerability of the brain to neurodegenerative diseases," said neuroscientist Manu Goyal of the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

"Brain metabolism might help us understand some of the differences we see between men and women as they age."

Scientists had already established that age-related grey matter volume decrease occurs more quickly in male brains than female brains. It's also been demonstrated that gene expression in the brain changes more rapidly in ageing men than women, resulting in a reduced ability to build and break down molecules in the male brain.

These pieces of evidence are suggestive of a form of neoteny in the female brain, (assuming male brains as the baseline, which is something scientists do), but no one had looked at metabolism - how the brain runs on glucose - until now.

As you age, the brain's use of glucose changes. In children, a metabolic process called aerobic glycolysis features heavily. It's associated with brain development, increasing in sync with synaptic formation and growth.

This process slows down as we approach adulthood, and continues to slowly decline. The brain still uses sugar for cognitive function, but aerobic glycolysis plateaus at a low level usually by the time people are in their 60s.

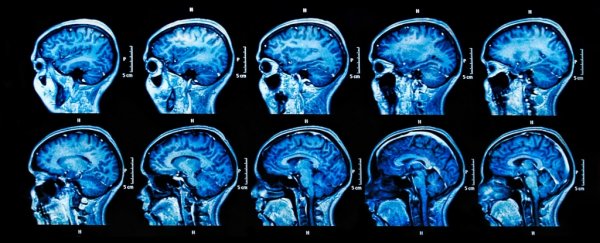

Obviously the exact age can vary from person to person, but to figure out if there are sex differences in that point, the research team conducted positron emission tomography (PET) scans on 205 people - 121 women and 84 men, from 20 to 82 years old.

The researchers were looking at the flow of oxygen and glucose in their brains to determine the proportion of the glucose that was being allocated to aerobic glycolysis.

They then fed a machine-learning algorithm the male sample data to establish a relationship between age and brain metabolism.

Using this as a baseline, the researchers asked the algorithm to estimate the ages of the women based solely on their brain metabolism data. It calculated that the women were, on average, 3.8 years younger than they actually were.

Then they did it in reverse. They used the women's data as a baseline, and estimated the men's ages based solely on their metabolism data. It calculated that the men were an average of 2.4 years older than their actual age.

And, even more interestingly, this difference was observed even in people as young as their 20s.

"It's not that men's brains age faster - they start adulthood about three years older than women, and that persists throughout life," Goyal said.

"What we don't know is what it means. I think this could mean that the reason women don't experience as much cognitive decline in later years is because their brains are effectively younger, and we're currently working on a study to confirm that."

In the next stage of their research, the team will be trying to determine if cognitive problems occur less frequently in people with brains that seem younger.

The team's research has been published in the journal PNAS.