The human liver stays youthful even while the rest of our bodies grow old, according to new research, and on average the organ is is less than three years old, no matter what the age of the person it's attached to.

Using mathematical modeling and a technique called retrospective radiocarbon birth dating – which dates human cells based on levels of a carbon isotope that spiked in the atmosphere following mid-20th century nuclear testing – scientists have found that liver renewal is largely unaffected as we grow old.

That renewal is key to the liver's primary function, which is clearing toxic substances out of the body. This waste removal takes its toll on the organ, but it has a unique ability to regenerate itself after being damaged.

"No matter if you are 20 or 84, your liver stays on average just under three years old," says molecular biologist Olaf Bergmann from the Dresden University of Technology in Germany.

The team analyzed post-mortem and biopsy tissue samples from more than 50 individuals aged between 20 and 84 years. They found our biology maintains tight control over the mass of the liver throughout our lives, via the continual replacement of liver cells.

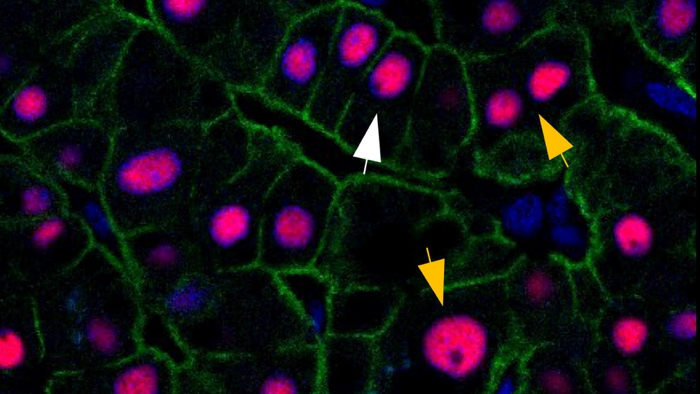

Liver cells under analysis. (Paula Heinke)

Liver cells under analysis. (Paula Heinke)

As our bodies get older, they're less able to renew cells and carry out repairs. What the new study shows is that this doesn't apply to the hepatocytes, the cells in the liver. Whereas earlier animal studies had given conflicting results, here there's much more clarity.

However, not all liver cells are the same in terms of how quickly they renew: A small fraction can live to be up to 10 years old, the researchers found. This seems to be related to how many sets of chromosomes they're carrying.

Most cells in our body, aside from our sex cells, carry two copies of our entire genome. Liver cells are an odd exception, with a proportion of cells generating even more copies of our whole DNA library on top.

"When we compared typical liver cells with the cells richer in DNA, we found fundamental differences in their renewal," says Bergmann. "Typical cells renew approximately once a year, while the cells richer in DNA can reside in the liver for up to a decade."

"As this fraction gradually increases with age, this could be a protective mechanism that safeguards us from accumulating harmful mutations. We need to find out if there are similar mechanisms in chronic liver disease, which in some cases can turn into cancer."

This is an important new insight into the biological mechanisms underpinning how the liver works – and of course the more we know about the organs in the body, the better we can get at figuring out how to keep them healthy and how to cure them from disease.

The researchers are also looking at other organs, including the heart, to see how fast cells are renewed across the body. The same technique of retrospective radiocarbon birth dating can be used to accurately date cells and work out renewal rates.

It's one of the best methods we've currently got for figuring out the age of human tissue, using the decay rates of radiocarbon in the atmosphere to correspond to traces in the body. As it turns out, your organs might not be as old as you feel.

"Our research shows that studying cell renewal directly in humans is technically very challenging but it can provide unparalleled insights into the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of human organ regeneration," says Bergmann.

The research has been published in Cell Systems.