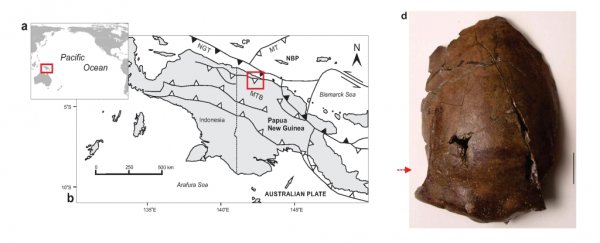

A 6,000-year-old skull fragment from the town of Aitape in Papua New Guinea probably belonged to the victim of a tsunami - a massive, devastating ocean wave.

Researchers have analysed the geological sediment from the area where the mid-Holocene skull was found in 1929, and found strong evidence that it was swept by a tsunami - indicating a possible cause of death for the skull's poor owner.

The skull was originally found buried in a mangrove by an Australian geologist called Paul Hossfeld. He retrieved it and took a field description of a region he called Paniri Creek, but didn't sample the sediment in which it was buried - so this is what the team of researchers travelled to Aitape to do.

"What we were doing was actually going in and sampling the sediments to bring back for lab analysis that would tell us a lot more about the age and depositional history there," explained researcher Mark Golitko of the University of Notre Dame.

The skull has always been of great interest, because it's one of the few human remains from the area from that time. Previous radiocarbon dating put its age at about 5,000 to 6,000 years old - at a time when ocean levels were higher, and the region would have been closer to the shoreline.

It's not know where, exactly, Hossfeld found the skull, but based on his field description, the team is fairly sure they were within 100 metres (328 feet) of its location.

When the team examined the sediment, they found a large number of remains from single-celled aquatic organisms called diatoms. These microalgae are enclosed in a cell wall constructed from silica, which remains behind after the diatom dies.

They are a good way for studying environmental conditions, and diatom paleontology can help reconstruct sedimentary environments and accurately gauge the age of sediment.

In the case of this skull, they can also help determine what happened in the area that it was found.

"These sediments that the Aitape skull was in have pure marine diatoms in them, which is ocean water that's inundating it," Golitko said.

"It's really high-energy ocean water - high-energy enough for these little tiny specks of silica that the diatoms build to be broken as they're washing in."

Combined with chemical signatures and the grain sizes found in the sediment, the sample is consistent with tsunami activity, and similar to that left behind after the 1998 tsunami that killed 2,000 people.

"Given the evidence we have in hand, we are more convinced than before that this person was either violently killed by a tsunami, or had their grave ripped open by one - leading to their head but not the rest of their body being naturally reburied where it then remained undiscovered in the ground for some 6,000 or so years," said researcher James Goff of the University of New South Wales in Australia.

According to what we know of tsunamis, Golitko believes that latter scenario is unlikely.

The researchers believe that studying the region may help understand how people adapt to and thrive in regions that are prone to natural disasters, given that the region has endured tsunamis for thousands of years.

"If we are right about how this person had died thousands of years ago, we have dramatic proof that living by the sea isn't always a life of beautiful golden sunsets and great surfing conditions," said one of the team, John Terrell of The Field Museum.

"Maybe this individual can help us as scientists to convince skeptics today that all of us on earth must take climate change and rising sea levels seriously as the threats they truly are."

The research has been published in the journal PLOS ONE.

UNSW Science is a sponsor of ScienceAlert. Find out more about their world-leading research.