For the first time, scientists have detected a giant neuron wrapped around the entire circumference of a mouse's brain, and it's so densely connected across both hemispheres, it could finally explain the origins of consciousness.

Using a new imaging technique, the team detected the giant neuron emanating from one of the best-connected regions in the brain, and say it could be coordinating signals from different areas to create conscious thought.

This recently discovered neuron is one of three that have been detected for the first time in a mammal's brain, and the new imaging technique could help us figure out if similar structures have gone undetected in our own brains for centuries.

At a recent meeting of the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies initiative in Maryland, a team from the Allen Institute for Brain Science described how all three neurons stretch across both hemispheres of the brain, but the largest one wraps around the organ's circumference like a "crown of thorns".

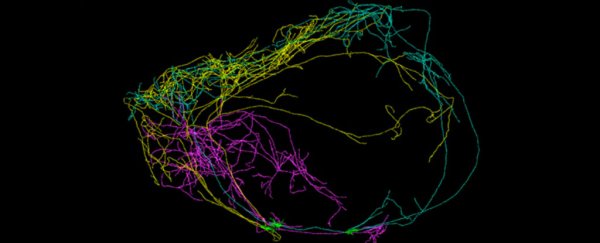

You can see them highlighted in the image at the top of the page.

Lead researcher Christof Koch told Sara Reardon at Nature that they've never seen neurons extend so far across both regions of the brain before.

Oddly enough, all three giant neurons happen to emanate from a part of the brain that's shown intriguing connections to human consciousness in the past - the claustrum, a thin sheet of grey matter that could be the most connected structure in the entire brain, based on volume.

This relatively small region is hidden between the inner surface of the neocortex in the centre of the brain, and communicates with almost all regions of cortex to achieve many higher cognitive functions such as language, long-term planning, and advanced sensory tasks such as seeing and hearing.

"Advanced brain-imaging techniques that look at the white matter fibres coursing to and from the claustrum reveal that it is a neural Grand Central Station," Koch wrote for Scientific American back in 2014. "Almost every region of the cortex sends fibres to the claustrum."

The claustrum is so densely connected to several crucial areas in the brain that Francis Crick of DNA double helix fame referred to it a "conductor of consciousness" in a 2005 paper co-written with Koch.

They suggested that it connects all of our external and internal perceptions together into a single unifying experience, like a conductor synchronises an orchestra, and strange medical cases in the past few years have only made their case stronger.

Back in 2014, a 54-year-old woman checked into the George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates in Washington, DC, for epilepsy treatment.

This involved gently probing various regions of her brain with electrodes to narrow down the potential source of her epileptic seizures, but when the team started stimulating the woman's claustrum, they found they could effectively 'switch' her consciousness off and on again.

Helen Thomson reported for New Scientist at the time:

"When the team zapped the area with high frequency electrical impulses, the woman lost consciousness. She stopped reading and stared blankly into space, she didn't respond to auditory or visual commands and her breathing slowed.

As soon as the stimulation stopped, she immediately regained consciousness with no memory of the event. The same thing happened every time the area was stimulated during two days of experiments."

According to Koch, who was not involved in the study, this kind of abrupt and specific 'stopping and starting' of consciousness had never been seen before.

Another experiment in 2015 examined the effects of claustrum lesions on the consciousness of 171 combat veterans with traumatic brain injuries.

They found that claustrum damage was associated with the duration, but not frequency, of loss of consciousness, suggesting that it could play an important role in the switching on and off of conscious thought, but another region could be involved in maintaining it.

And now Koch and his team have discovered extensive neurons in mouse brains emanating from this mysterious region.

In order to map neurons, researchers usually have to inject individual nerve cells with a dye, cut the brain into thin sections, and then trace the neuron's path by hand.

It's a surprisingly rudimentary technique for a neuroscientist to have to perform, and given that they have to destroy the brain in the process, it's not one that can be done regularly on human organs.

Koch and his team wanted to come up with a technique that was less invasive, and engineered mice that could have specific genes in their claustrum neurons activated by a specific drug.

"When the researchers fed the mice a small amount of the drug, only a handful of neurons received enough of it to switch on these genes," Reardon reports for Nature.

"That resulted in production of a green fluorescent protein that spread throughout the entire neuron. The team then took 10,000 cross-sectional images of the mouse brain, and used a computer program to create a 3D reconstruction of just three glowing cells."

We should keep in mind that just because these new giant neurons are connected to the claustrum doesn't mean that Koch's hypothesis about consciousness is correct - we're a long way from proving that yet.

It's also important to note that these neurons have only been detected in mice so far, and the research has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, so we need to wait for further confirmation before we can really delve into what this discovery could mean for humans.

But the discovery is an intriguing piece of the puzzle that could help up make sense of this crucial, but enigmatic region of the brain, and how it could relate to the human experience of conscious thought.

The research was presented at the 15 February meeting of the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies initiative in Bethesda, Maryland.