A theoretical physicist has come up with a new hypothesis that could finally explain the mystery of dark matter - the elusive matter that's predicted to make up around 27 percent of the observable Universe.

According to the new paper, all we have to do to explain the weird effects of dark matter in the Universe is take gravity out of the equation.

"Our current ideas about space, time, and gravity urgently need to be re-thought. We have long known that Einstein's theory of gravity can not work with quantum mechanics", the author the new paper, Erik Verlinde from the University of Amsterdam, told Dutch news site NOS.

"Our findings are drastically changing, and I think that we are on the eve of a scientific revolution."

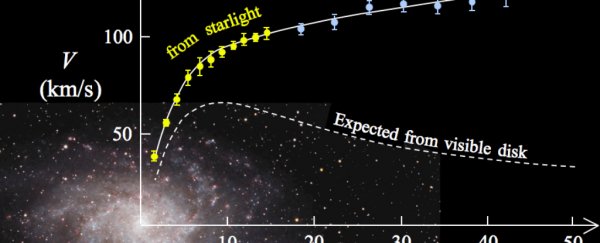

The dark matter problem stems from the fact that there's more gravity in our Universe - especially in our galaxies - than can be produced by all the matter and gas that we see.

Traditionally, physicists have explained this inconsistency by assuming that there must be something else out there that we can't see, something dark - hence the name dark matter.

Physicists predict that dark matter makes up around 27 percent of all the mass and energy in the observable Universe - in fact, if galaxies didn't have dark matter, gravity alone wouldn't be enough to hold them together - but no one has been able to figure out what it is as yet.

There have been several leading candidates for a dark matter particle, but many of these have been ruled out with further testing. And one of the largest and most expensive searches for dark matter to date recently turned up nothing.

So Verlinde decided to look at the problem another way. If we only proposed dark matter to make up for an inconsistency with gravity, then maybe the issue isn't dark matter at all - maybe the problem is that we don't really understand how gravity works.

Dark matter isn't the only gravitational inconsistency, either. The Standard Model of physics - the best set of formulae we have to explain how the Universe works - doesn't explain the effects of gravity.

And gravity and other general relativity theories famously don't gel with our understanding of quantum mechanics, which has led researchers to seek out a new 'theory of everything' that bridges the two.

But Verlinde has taken a different approach, by taking gravity out of the picture altogether. His suggestion is that gravity isn't a fundamental force of nature at all, but rather an emergent phenomenon - just like temperature is an emergent phenomenon that arises from the movement of microscopic particles.

In other words, gravity is a side effect, not the cause, of what's happening in the Universe.

Verlinde first proposed this radical new hypothesis of gravity back in 2010. But now he's shown than when you factor this new definition of gravity into the Universe, we no longer need to find a new particle to account for dark matter - the behaviour of galaxies makes sense without it.

"We have evidence that this new view of gravity actually agrees with the observations, " he said. "At large scales, it seems, gravity just doesn't behave the way Einstein's theory predicts."

To come to this conclusion, he went back to the drawing board to figure out exactly how gravity forms on a microscopic level. His calculations suggest that gravity is an emergent phenomenon that arises from the entropy of the Universe.

Entropy is a property of thermodynamics that describes how much wasted energy there is in a system - or, more simply, how chaotic a system is.

You can also describe this is as how much information it takes to describe a system - generally, the more chaotic something is, the more information it takes to describe it, and the more entropy it has.

Verlinde's model takes entropy and applies something known as the holographic principle. The basic idea is that there's fundamental bits of information stored in the fabric of space time - Verlinde describes these as 'atoms' of space - and these bits of information can shift in order to move towards high entropy.

According to Verlinde's calculations, this shift produces an entropic force that acts like gravity.

He explains the idea in more detail in the video below:

The challenge now is testing this new hypothesis. The simplest way to disprove it would be to find a particle that explains dark matter. But physicists will also be able to confirm or falsify the new hypothesis by applying Verlinde's model of gravity to our observations of the Universe.

Verlinde has now put his paper up on the pre-print server arXiv.org so the physics community can pick over it and begin to test it out. But it's important to note that it hasn't been published in a peer-reviewed journal, so we need to take it with a big grain of salt.

Still, it's an interesting idea. And even if this turns out to be the wrong way of thinking about gravity - just like so many previous hypotheses have been - it's always a good idea to look outside the box for new ways of approaching a problem.

Because if we want to get that long-awaited theory of everything, it's looking more and more likely that some part of our understanding of how the Universe works is going to have to shift.

"Many theoretical physicists like me are working on a revision of the theory, and some major advancements have been made," said Verlinde. "We might be standing on the brink of a new scientific revolution that will radically change our views on the very nature of space, time and gravity."

You can read the full paper here.