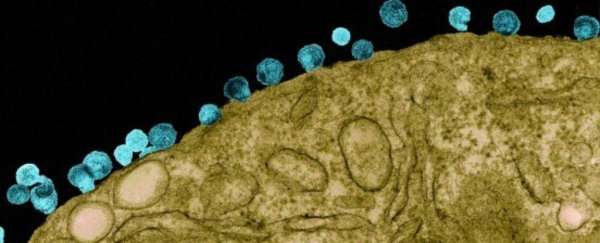

A new trial has shown that a single dose of antibodies can prevent monkeys from contracting the primate version of HIV for nearly six months.

It's a promising result that suggests we might finally be on the verge of a long-term prevention option. With all our best attempts at creating a vaccine having failed so far, a treatment like this just might be our best shot at slowing the spread of HIV.

"This study is the first one to show that a single administration of these monoclonal antibodies can prevent infection, prevent disease, and might be a viable alternative for a vaccine against HIV," one of the researchers, Malcolm Martin from the US's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told Alessandra Potenza over at The Verge. "That's a new finding."

The difference between a vaccine and our immune system's antibodies is the fact that a vaccine contains a harmless version of a virus, designed to trigger a patient's own antibodies to take down an infection when needed. An antibody treatment, on the other hand, injects people with extra antibodies to fight the virus immediately.

This isn't the first time that an antibody treatment approach has been shown to work against HIV, but in the past, they've been tested by injecting monkeys with a single high-dose shot of the virus. In the real world, most humans become infected after being exposed to low doses of the virus on several occasions, which is what Martin's team tested their monkeys with.

Publishing in Nature, the researchers report that the monkeys remained protected for up to 23 weeks of being injected with low-doses of HIV.

"The result is surprising," said the director of the Texas Biomedical Research Institute's AIDS Research Program, Ruth Ruprecht, who wasn't involved in the study. "I am astonished by how long protection lasted."

Of course, we already have preventative treatments against HIV - such as PrEP, which reduces the risk fo being infected from sex by more than 90 percent - but the pill needs to be taken every single day, and research has suggested that this strategy isn't working so well anyway. In 2014, almost 2 million people became newly infected with HIV.

A better alternative would be a one-off treatment that offers long-term protection, such as injection every six months.

To test out if this could work, the researchers took four powerful antibodies known to attack HIV. These antibodies were produced in humans and purified in the lab, and each was injected into a different group of six Rhesus macaque monkeys.

One week after they'd been treated, the monkeys started being exposed to weekly low doses of a primate version of the HIV virus (the human version only infects us) and, on average, were protected for 12 to 14 weeks. In some animals, the antibodies fought of the virus for 23 weeks.

A control group showed that it took on average just three weeks for untreated animals to become infected.

There are limitations to the study: Ruprecht told Potenza that using a cocktail of antibodies, rather than just a single antibody, would have been more effective. But Martin explains that at this early stage, the team wants to figure out how effective each antibody is on its own, before combining it.

To that end, a clinical trial of one of the antibodies used in the study, antibody VRC01, has just started in Brazil, Peru, and the US. The study will involve 2,700 people who are at high-risk of infection, and in a few months will expand to African nations including South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, and Tanzania.

The results are expected to be in by 2022, and if they're positive, the team will then work on optimising a longer-lasting treatment in humans.

The best part about all of this is that there's reason to suspect the treatment could work even better in people, seeing as human antibodies aren't optimised in monkeys.

"What the data in this study is suggesting is that six months [of protection] may be achievable and with improved technologies we might even do better than that," director of the Laboratory for AIDS Vaccine Research and Development at Duke University, David Montefiori, who wasn't involved in the study, told The Verge.

"With the extraordinary progress that's been made just in the past six years, I'm more optimistic than ever that the field will eventually succeed in having an effective prevention measure," he added. "Hopefully, we'll see the light at the end of the tunnel within the next 10 years."