Scientists are claiming that the classification of two major dinosaur groups has been wrong for over a century, and if they're right, it would be like everyone realising that some types of "cats" are actually dogs.

The controversial paper has also suggested that the physical location of the first dinosaurs might be incorrect – pointing to a previously unimportant cat-sized fossil in Scotland as their evidence.

"This is a textbook changer - if it continues to pan out," palaeontologist Thomas Holtz from University of Maryland, who wasn't involved in the research, told Nature.

"It's only one analysis, but it's a thorough one."

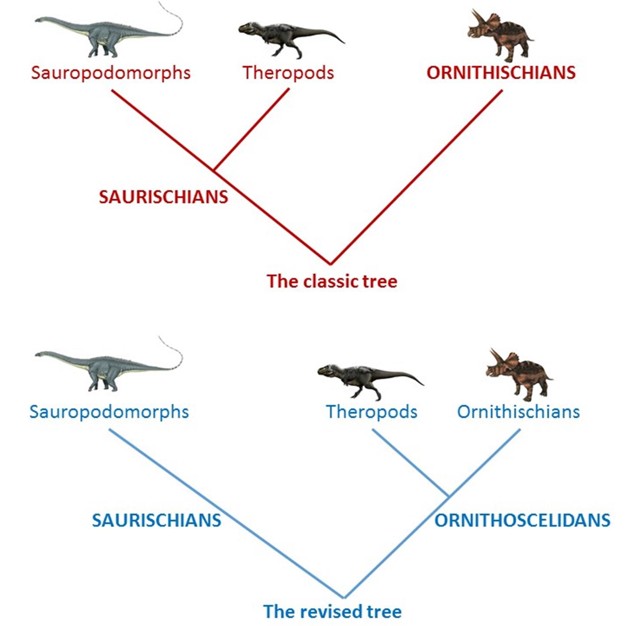

Right now, the dinosaur evolutionary tree divides dinosaurs up into two groups: Ornithischia and Saurischia.

Species have been placed into one of these groups depending on their hip bone structure – if their hips were bird-like, they're an ornithischian, if their hips were lizard-like, they're a saurischian.

As Hannah Devlin explains over at The Guardian, the bird-like Ornithischia group includes relatives of Stegosaurus and Triceratops, whereas theropods such as Tyrannosaurus rex, sauropods such as Diplodocus, and a meat-eating group called the Herrerasauridae all fell within the lizard-hipped Saurischia group.

Now, researchers from the Natural History Museum in London say this might not be the case at all, based on their analysis of 457 anatomical features from 74 dinosaur species across both groups.

The team's hypothesis is that the theropod meat-eating beasts may have been wrongly classified – citing a number of similarities between the theropods and the Ornithischia group.

The analysis indicates that the theropods and the Ornithischias share 21 anatomical traits, such as a distinctive ridge on their jaw, and a particular bone fusion in their feet.

Dmitry Bogdanov, Torley, Durbed

Dmitry Bogdanov, Torley, Durbed

"Luckily, most of what we've pieced together about dinosaurs - how they fed, breathed, moved, reproduced, grew up, and socialised - will stand unchanged," Lindsay Zanno from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, who was not involved in the study, told Ed Yong at The Atlantic.

"[But] these conclusions lead us to question the most basic structure of the entire dinosaur family tree, which we have used as the backbone of our research for over a century."

"If confirmed by independent studies," she adds, "the changes will shake dinosaur palaeontology to its core."

But that's not all.

Until this study, the research had placed the emergence of dinosaurs at around 237 million years ago on the Gondwana super-continent, in an area that would later become the Southern Hemisphere.

With this redrawing of the dinosaur family tree, a previously unimportant fossil from Scotland called Saltopus might now have a much more central role.

The researchers think this cat-sized specimen could be a common ancestor to all dinosaurs – putting their emergence 5 million years earlier than the currently accepted estimates.

"The northern continents certainly played a much bigger role in dinosaur evolution than we previously thought and dinosaurs may have originated in the UK," Matthew Baron, the lead researcher on the paper, told Pallab Ghosh at the BBC.

But not everyone agrees.

"There's nothing special about this [Saltopus] guy," Max Langer, a palaeontologist from the University of São Paulo in Brazil, told Hannah Devlin at The Guardian.

"Saltopus is the right place in terms of evolution, but you have much better fossils that would be better candidates for such a dinosaur precursor."

The fossil comprises a pair of legs, some hip bones, and a vertebra – all of which are pretty badly squashed.

Even the researchers acknowledge it's not in the best shape.

"It looks like a chicken carcass after a Sunday roast," Baron explains to Devlin.

However, for such a controversial and historic paper, there have been quite a few influential backers.

In a Nature piece accompanying the paper, palaeontologist Kevin Padian from the University of California, Berkeley who was not involved in the research, calls the study an "original and provocative reassessment of dinosaur origins and relationships".

"When we do these other analyses, we sometimes get very different results," palaeobiologist Jakob Vinther from the University of Bristol, who was also not involved with the paper told The Guardian.

"I get the same result."

If accepted into the literature, the revised evolutionary tree would also need the formal definition of dinosaurs to be rewritten – potentially kicking long-necked herbivores, such as Brontosaurus and Diplodocus, outside the dinosaur family tree.

"I didn't want to make Dippy not a dinosaur. That would have created a lot of upset," Baron told Ghosh.

Dippy of course being the iconic skeleton that was displayed at the Natural History Museum for 112 years.

"To be truthful, I didn't want to be chased out of every conference I went to for the rest of my career."

No matter the outcome of this research paper, what we are seeing is historic science in action.

It's not every day scientists get to argue if 130 years of dinosaur knowledge is wrong.

Watch this space - we're looking forward to seeing what happens next.

The research has been published in Nature.