Tiny fungi that grow in the cracks of Antarctic rocks have just spent 18 months on board the International Space Station (ISS) in conditions similar to those on Mars, and 60 percent of their cells survived with stable DNA, new research reveals.

The results will help scientists better understand what type of lifeforms may have once lived on the Red Planet - and potentially still exist there - and will give them some insight into what they should be looking for.

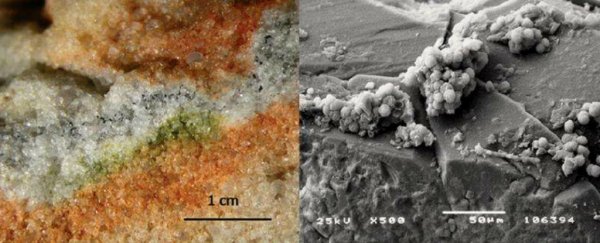

The fungi in question are known as cryptoendolithic fungi, and two species were collected by European scientists and sent to the ISS: Cryomyces antarcticus and Cryomyces minteri.

Both species were taken from the McMurdo Dry Valleys, which are located in the Antarctic Victoria Land and, thanks to their dry, hostile conditions, are generally considered to be the most similar Earth environment to Mars.

Only tiny microorganisms that live in the cracks of rocks are able to survive the strong winds and freezing cold, but on Mars there are even bigger problems to worry about, such as the high levels of ionising radiation and lack of oxygen.

To test how the fungi would cope, scientists collected them from their Antarctic rocks and placed them inside cells on a platform known as EXPOSE-E, which was specially developed by the European Space Agency to withstand extreme environments.

Once safely stored, the EXPOSE-E platform was sent up to the ISS in the Space Shuttle Atlantis, and tended to by an astronaut on board.

For the next 18 months, half of the fungi were exposed to Mars-like conditions, which meant that they were put in an atmosphere made up of 95 percent CO2, 1.6 percent argon, 0.15 percent oxygen, and 2.7 percent nitrogen, with 370 parts per million of water.

The samples were also subjected to pressure of 1,000 pascals, and were bombarded with ultraviolet radiation higher than 200 nanometres, as they'd be exposed to on Mars.

"The most relevant outcome was that more than 60 percent of the cells of the endolithic communities studied remained intact after 'exposure to Mars', or rather, the stability of their cellular DNA was still high," said one of the researchers, Rosa de la Torre Noetzel, from Spain's National Institute of Aerospace Technology.

Only 10 percent of the samples were able to proliferate and form colonies after being exposed to the Martian conditions, but the fact that so many cells survived is an incredibly promising sign, and has been described in the journal Astrobiology.

Another set of the fungi samples were also tested on board the ISS, but they were subjected to even harsher space conditions, which means temperature fluctuations between -21.5 and 59.6 degrees Celsius, and galactic-cosmic radiation of up to 190 megagrays.

Under these conditions, the Antarctic fungi also showed a huge amount of resilience, with 35 percent of cells remaining in tact at the end of the 18 months.

The experiment was part of the bigger Lichens and Fungi Experiment (LIFE), and two samples of lichens - one taken from Spain and one from the Alps of Austria - were also tested in the extreme conditions.

The success rate of the lichens hasn't been published as yet, but the results so far seem promising.

"The results help to assess the survival ability and long-term stability of microorganisms and bioindicators on the surface of Mars," said De la Torre. "Information which becomes fundamental and relevant for future experiments centred around the search for life on the Red Planet."

In other words, if we know what types of organisms can survive Mars's harsh conditions, it might give us some clues as to what we should be looking for on the Red Planet. And that's pretty damn exciting.