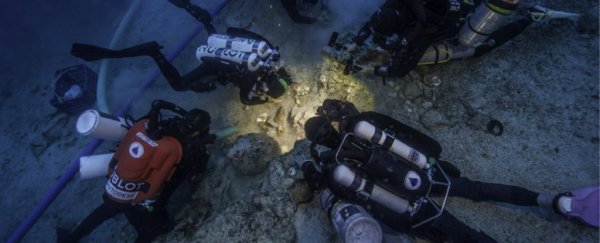

An international team of archaeologists excavating the famous Antikythera shipwreck in the Aegean Sea off the coast of Greece have found the remains of a human skeleton among the 2,100-year-old wreckage.

If they can extract DNA from the bones, it'll help us understand more about the passengers on board the ship when it sank around 65 BC – and could provide vital insight into the mysterious Antikythera Mechanism it was carrying, better known as the world's first computer.

"Archaeologists study the human past through the objects our ancestors created," said team member Brendan Foley, from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in the US.

"With the Antikythera Shipwreck, we can now connect directly with this person who sailed and died aboard the Antikythera ship."

In case you're unfamiliar, the Antikythera shipwreck – which was originally discovered by sponge divers in 1900 – is the largest ancient shipwreck ever found.

During the first excavation by the sponge divers, they managed to pull up a series of marble statues and thousands of other sea-battered artefacts.

Among the random assortment of things was the Antikythera Mechanism, a clockwork device that might have been used to predict astronomical events and is widely referred to as the world's first analogue computer.

The Antikythera Mechanism. Image: Marsyas/WikiCommons

The Antikythera Mechanism. Image: Marsyas/WikiCommons

Researchers have dated the device to around 100 or 150 BC, which means that – after it sank – similar technology didn't pop up around the world until at least the 14th century AD, which makes the device all the more fascinating.

In 1976, famed ocean explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau and his crew returned to wreckage after it laid untouched for nearly 80 years. They were able to pull up some 300 objects, including skeletal remains, though DNA technology wasn't available back then to fully analyse them.

Now, a new team – consisting of researchers from WHOI and the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – has uncovered more remains beneath shards of pottery, and this time they hope to shed new light on who was on board the ill-fated ship, where they were from, and where they might have been going.

The newly found remains were pulled up on 31 August and – after they get released by the Greek government – will be sent to researchers at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen for further analysis.

"Against all odds, the bones survived over 2,000 years at the bottom of the sea and they appear to be in fairly good condition, which is incredible," said DNA expert Hannes Schroeder, from Natural History Museum of Denmark.

In addition to finding these incredible remains, the archaeologists working at the site have also started to use 3D imaging to instantly share their findings with other researchers – and the public, too – without even having to pull them to the surface.

We're still waiting on a peer-reviewed paper to be published about the new find, so right now we're taking the researchers' words for it, but we imagine they're going to hold off writing anything up until they have the DNA analysis results.

That said, there's no guarantee DNA sequencing will work on a skeleton of this age – especially one that's been at the bottom of the sea for millennia – but if it does, we could finally have more information on one of the oldest, largest, and most mysterious shipwrecks ever to be found.

We love how excited the archaeologists were when they first spotted the remains. We're right there with you, guys.