Most of us are sick of hearing about the 'fake news crisis' plaguing social media. But a new study shows that it might be more of an issue than we want to admit, with even the next-generation of internet-literate students proving unable to tell fake from real news.

A new study has shown that up to 80 percent of middle school students surveyed in the US couldn't tell the difference between sponsored content and a real news story. And more than 80 percent of high schoolers didn't have a problem taking facts from an anonymous Imgur post.

"Many people assume that because young people are fluent in social media they are equally perceptive about what they find there," said lead researcher Sam Wineburg from Stanford University. "Our work shows the opposite to be true."

Fake news refers to news from dubious sources, advertising content, or stories that are just totally made up - but which still go viral on Facebook and Twitter.

For example - stories saying that Pope Francis endorsed Donald Trump (he didn't), or the false headlines about the FBI agent who apparently investigated Hilary Clinton's emails being found dead in his apartment.

Over the past few months, social media and tech giants have been cracking down on this type of illegitimate news.

But a lot of us are kinda fatigued on the issue. After all, anyone who uses the internet regularly can surely tell the difference between bogus and real news, right?

Well, if these new results are anything to go by, no, no they can't. And that's a real problem.

The Stanford researchers admitted to being "shocked" by the results.

"In every case and at every level, we were taken aback by students' lack of preparation," they write in their report.

The researchers surveyed a total of 7,804 students ranging in age from middle school to college level across 12 US states, and gave them a range of different activities based on their education level.

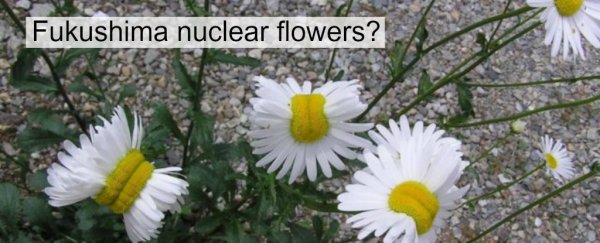

One exercise asked high school students to rate the trustworthiness of an Imgur photo of deformed daises with the headline "Fukushima Nuclear Flowers: Not much more to say, this is what happens when flowers get nuclear birth defects."

The real story is that those daises were photographed near Fukushima, but it's highly unlikely that their state has anything to do with the nuclear power plant melt down.

When quizzed, only 20 percent of the students thought the anonymous photo was a little dubious, and 40 percent of high-school students believed that the photo was "strong evidence" that the region around Fukushima was toxic.

"We asked students, 'Does this photograph provide proof that the kind of nuclear disaster caused these aberrations in nature?' And we found that over 80 percent of the high school students that we gave this to had an extremely difficult time making that determination," Wineburg told NPR.

"They didn't ask where it came from. They didn't verify it. They simply accepted the picture as fact."

The team also asked middle-school students to look at the homepage of the news site Slate and identify whether content was a news story or an ad.

The students were able to identify traditional ads, such as banner ads, but out of the 203 students, more than 80 percent thought that a native ad about finance - which was identified with the words "sponsored content" - was a real news story.

Students also struggled to identify which sources were legit and which weren't, and often ignored things like the authenticated tick on verified Facebook and Twitter accounts.

In one exercise, 30 percent of the students argued that a fake Fox News account was more trustworthy than the verified account because it used better graphics.

Even at the college level, participants struggled to identify the political views of candidates based on Google search information.

The research has been published in full by the Stanford History Education Group, but it has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, so the results need to be replicated and verified before we can read too much into it.

But with 62 percent of US adults admitting to getting the majority of their news from social media these days, it's a problem when even the future of our planet are struggling to know what's okay to share and what isn't.

Google and Facebook say they're both working on banning fake news organisations, but in the meantime, the researchers say we need to focus on better educating students on the issue at school.

"What we see is a rash of fake news going on that people pass on without thinking," Wineburg told NPR. "And we really can't blame young people because we've never taught them to do otherwise."

"The kinds of duties that used to be the responsibility of editors, of librarians now fall on the shoulders of anyone who uses a screen to become informed about the world," he added.

"And so the response is not to take away these rights from ordinary citizens but to teach them how to thoughtfully engage in information seeking and evaluating in a cacophonous democracy."

You can read the full report here.