The results of a huge project to sequence the traces of DNA left on New York City's subways have given us the first comprehensive look at the bacterial menagerie hosted by one of the world's most trafficked public transport systems.

Cities are just like human beings, in the sense that we both harbour an incredibly rich variety of microbes in our every nook and cranny. The average human, for example, contains about 100 trillion microbial cells, which outnumber human cells by a 10:1 ratio, and make up 36 percent of the active molecules floating through the human bloodstream. We might be the brains of the operation, but our bodies are giant, walking petri dishes full of all kinds of microscopic creatures, living, feeding, and breathing all over us, and without them, we'd die.

As we move about the cities we live in, we leave behind about 1.5 million microscopic skin cells every hour, says Robert Lee Hotz at The Wall Street Journal, and scientists have seen populations of them form new colonies in places such as hotel rooms in as little as six hours time. So, much like humans, each city contains its unique and incredibly rich microbial population, and each area within a city contains a smaller, more unique population inside that. And what scientists are interested in now is gaining a better understanding of what, exactly, makes up those populations, so they can identify when changes are occurring, such as at the beginning of a major disease outbreak.

"We know next to nothing about the ecology of urban environments," evolutionary biologist Jonathan Eisen at the University of California at Davis told Hotz. "How will we know if there is something abnormal if we don't know what normal is?"

Enter the PathoMap project, led by Christopher Mason, a geneticist at Weill Cornell Medical College in the US. This massive study involved sampling a bunch of different surfaces across 466 open stations in New York City, including on the kiosks, benches, turnstiles, garbage cans, and railings, over an 18-month period. The project ended up finding more than 10 billion fragments of biochemical code, which the scientists fed into a supercomputer armed with the extensive genetic databases of all known plants, animals, viral and bacterial life. This then produced an incredible map of how the 15,152 different types of life-forms this DNA belonged to were spread throughout the city.

Of the DNA, 46.9 percent came from bacteria, most of which was harmless, and 48 percent did not match any known organism. That's not to say that New York City is teeming with unidentified lifeforms, but rather how much work scientists have got to do to sequence the genomes of everything around us. To give you an idea, here's how many organisms have had their genomes sequenced so far. When you think about how many organisms exist, that 48 percent doesn't actually seem that bad.

But on to the specifics. Hotz runs through some of the most intriguing results at The Wall Street Journal:

"In 18 months of scouring the entire system, [Mason] has found germs that can cause bubonic plague uptown, meningitis in midtown, stomach trouble in the financial district and antibiotic-resistant infections throughout the boroughs.

Frequently, he and his team also found bacteria that keep the city liveable, by sopping up hazardous chemicals or digesting toxic waste. They could even track the trail of bacteria created by the city's taste for pizza - identifying microbes associated with cheese and sausage at scores of subway stops.

Among the DNA of higher organisms, the researchers found across the system that genetic material from beetles and flies was the most prevalent - the cockroach genome hasn't been sequenced yet so that DNA wasn't identified. Cucumber DNA ranked third - possibly from lunch leftovers, or from the computer grouping partial DNA from other plants into the nearest known species."

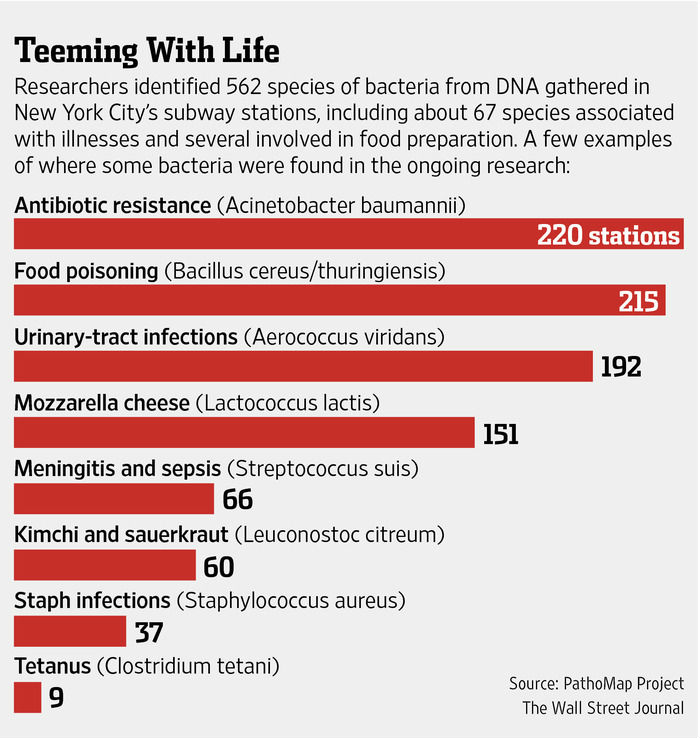

So far, the team has identified 562 species of bacteria from the DNA they collected, with at least 67 of these capable of making people sick. As you can see in the graph above, drug-resistant bacteria were found in almost half the tested locations, as were the bacteria that are responsible for food poisoning. They even found a trace of anthrax DNA on the railing at one station and the handhold of one train, plus traces of the bacteria that cause the bubonic plague at three stations, but say this does not mean the public is at risk of developing either disease.

The results, which were published in the journal Cell Systems, also answered a question that no one was asking - no, Tasmanian devils, Himalayan yaks and Mediterranean fruit flies have never commuted across New York City via the subway system. Good to know.

Head over to Robert Lee Hotz's article to find out more about how the brave team from the Weill Cornell Medical College navigated their way around rats, vomit, and condoms to gather the DNA they needed for the survey. I've said it once and I'll say it again - scientists are the real heroes.

Source: The Wall Street Journal