In a landmark moment for scientific research, the world's first gene therapy treatment for children has been given the green light by the European Commission. It's called Strimvelis, and it treats severe combined immunodeficiency (ADA-SCID) – a rare disorder that can be fatal in a very short space of time for those affected.

The disease leaves newborns with almost no defence against viruses and bacteria, and is closely linked to X-linked SCID or 'bubble boy' disease, so-called because of a young patient in the US who lived inside a protective plastic shield. What makes the new treatment special is that it's the first time a commercial treatment has used genetic repair techniques to cure a disorder, and thanks to success in clinical trials, it's now approved for marketing within Europe.

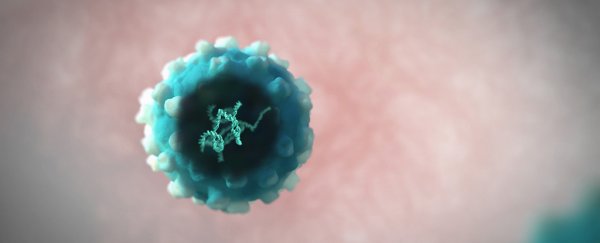

ADA-SCID is caused by a faulty gene inherited by both parents, and affects around 15 patients per year in Europe. The faulty gene stops the production of the adenosine deaminase (ADA) protein, which is required to produce white blood cells called lymphocytes. The disease often proves fatal before a child's first birthday.

The disease is currently treated using a risky bone marrow transplant or lifelong and very expensive enzyme replacement therapy. In the case of Strimvelis, stem cells are removed from a patient's bone marrow, corrected in a test tube to replace the faulty gene, and then reintroduced into the body.

"If you want to fix a disease for life, you need to put the gene in the stem cells," paediatrician Maria-Grazia Roncarolo from Stanford University explained to Antonio Regalado at MIT Technology Review. Roncarolo was the leader of the team who originally tested the Strimvelis treatment.

"This is the start of a new chapter in the treatment of rare genetic diseases and we hope that this therapeutic approach could also be used to help patients with other rare diseases in the future," said Martin Andrews, head of the Rare Disease Unit at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the company behind the treatment.

Gene therapy techniques are still so new that scientists and regulators are wary of introducing them too soon. This method of treatment has the potential to be hugely beneficial for medical science, but is essentially playing with the most fundamental building blocks of life. Swapping out genetic code is a lot more complicated than replacing a part in a car engine, though the principle is the same.

Of 18 children treated with Strimvelis in clinical trials, researchers found a 100 percent survival rate based on follow-up durations of between 2.3 and 13.4 years, which suggests that Strimvelis can indeed replace faulty genes with working copies without any adverse side effects – something that can't be said for existing treatments.

"I would be hesitant to call it a cure," GSK head of gene therapy development Sven Kili told MIT Technology Review. "Although there's no reason to think it won't last."

The results of the clinical trials have been published in Blood.