Adding a common female hormone to an existing breast cancer drug can impede tumour growth and increase survival rates, a new study suggests.

While the results have so far only been tested on mice and cultured human breast cells, the team says they could lead to a new, low-cost treatment for the millions of breast cancer patients around the world who are currently facing the lowest survival rates.

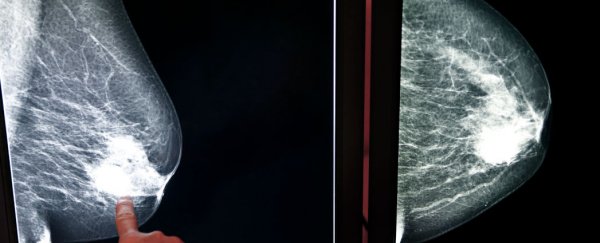

One of the biggest challenges in trying to better understand and treat breast cancer is that it behaves differently depending on a patient's unique hormonal balance. Looking into a particular type of breast cancer that affects at least half of all patients worldwide - called oestrogen receptor positive (ER+) cancer - researchers have been puzzled to find that patients with naturally high levels of a particular hormone receptor typically have a better survival rate than those who don't.

But a new study has finally figured out why. ER+ cancer growth is driven by the hormone oestrogen acting on oestrogen receptor molecules inside the structure of the tumour. These oestrogen receptors bind to the tumour cells and activate their growth and proliferation, which is why ER+ patients are often treated with an oestrogen-blocking drug called tamoxifen.

Not all patients respond to this drug in the same way, however, and it looks like the hormone progesterone could be a major factor in determining how successful this treatment is. A team of researchers from the UK and Australia tested this out by giving mice with breast cancer and cultured human breast cancer cells an extra dose of progesterone. This appeared to activate progesterone receptors in the breast tumours, which then directly affected the activity of the oestrogen receptors.

"It actually interacts with the oestrogen receptor to alter the way it works in a tumour cell," one of the team Wayne Tilley from the University of Adelaide in South Australia told Anna Salleh at ABC News. "If the progesterone receptor is not there, then the oestrogen receptor switches on all these genes that are associated with stimulating tumour growth and stimulating metastasis."

This means if people have low levels of progesterone receptors, the oestrogen receptors are free to switch on aggressive genes that drive cancer growth and make hormone therapy less effective. "When the progesterone receptor is there, the oestrogen receptor sits in different parts of the DNA. You don't switch on those nasty genes but switch on those associated with a better outcome," says Tilley.

When mice with breast cancer were given a treatment of tamoxifen combined with progesterone, the growth of their tumours slowed significantly more than in mice that were just giving the tamoxifen alone. "Tests showed that mice given progesterone and tamoxifen had breast tumours only half the size of those given the drug on its own," Ian Sample reports for The Guardian.

The results are promising, and they do help to explain why some ER+ cancer patients end up with better survival rates than other. But in terms of better treatments in the future, they need to be replicated in human clinical trials, which is what Tilley and his team are now looking into. "It provides a strong case for a clinical trial to investigate the potential benefit of adding progesterone to drugs that target the oestrogen receptor, which could improve treatment for the majority of hormone-driven breast cancers," one of the team Jason Carroll from the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, told News.com.au.

The results were published in Nature.