A recent report has found that over the past two decades, we've lost a tenth of the world's wilderness, thanks in no small part to mining, illegal logging, agriculture, and oil and gas exploration.

That means since 1993, an area twice the size of Alaska has been stripped from the plant and animal species that depend on it, and wilderness now amounts to just 23 percent of Earth's total land mass.

"The continued loss of wilderness areas is a globally significant problem with largely irreversible outcomes for both humans and nature," says the international team of researchers behind the study.

"If these trends continue, there could be no globally significant wilderness areas left in less than a century."

The researchers found that the Amazon and Central Africa have been hardest hit when it comes to declining wilderness - defined as biologically and ecologically intact landscapes that are mostly free of human disturbance.

"These areas do not exclude people, as many are in fact critical to certain communities, including indigenous people," the researchers stipulate.

"Rather, they have lower levels of impacts from the kinds of human uses that result in significant biophysical disturbance to natural habitats, such as large-scale land conversion, industrial activity, or infrastructure development."

Of the 3.3 million square kilometres of wilderness lost since 1993, the Amazon accounted for nearly a third, while a further 14 percent was lost from Central Africa. The researchers concluded that 30.1 million square kilometres of wilderness was left, which equates to less than a quarter of the planet's total land mass.

And what's perhaps most worrying is the fact that wilderness is being destroyed at a faster rate than we're establishing protected areas. In the same period of time that we lost 3.3 million sq km, new reserves totalled 2.5 million sq km.

"The amount of wilderness loss in just two decades is staggering and very saddening," says one of the team, James Watson, from the University of Queensland in Australia and the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York.

"You cannot restore wilderness. Once it is gone, the ecological processes that underpin these ecosystems are gone, and it never comes back to the state it was. The only option is to proactively protect what is left."

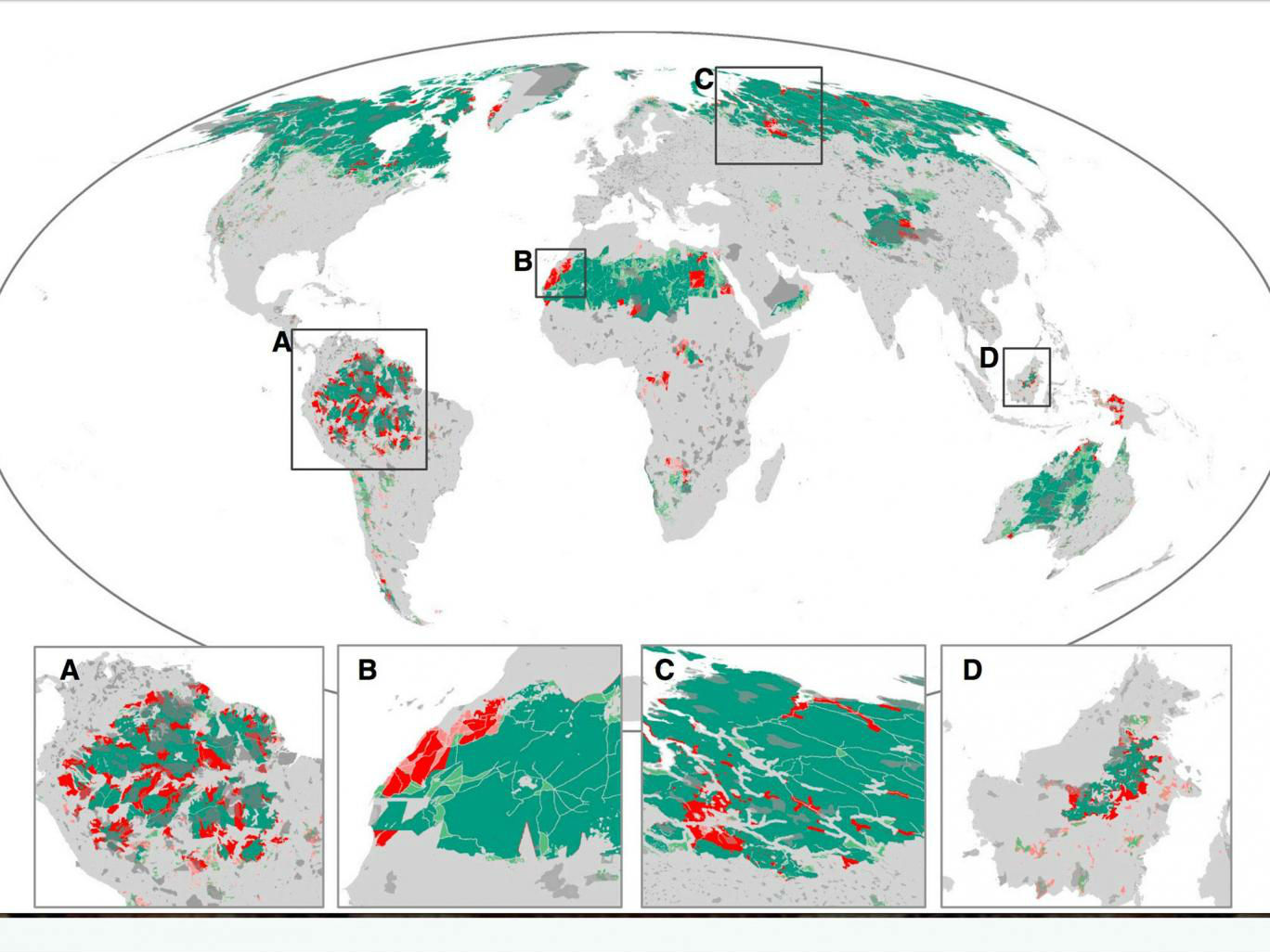

Map showing the remaining wilderness areas in green and the losses over the last two decades in red. Dark grey indicates protected areas like national parks. Watson et al

Map showing the remaining wilderness areas in green and the losses over the last two decades in red. Dark grey indicates protected areas like national parks. Watson et al

The team found that the majority of the wilderness left on Earth was located in North America, North Asia, North Africa, and the Australian continent, and said what's encouraging is the fact that the majority of wilderness - 82.3 percent, or 25.2 million sq km - is still composed of vast, uninterrupted areas of at least 10,000 sq km.

If the remaining wilderness was fragmented into much smaller areas, we'd be in a far more dire situation than we're in right now, because smaller areas are not only harder to maintain, under 10,000 sq km, it's almost impossible to get an accurate reading on the ecological communities present.

The team cites two examples of conservation efforts that should make a real difference in the future. They mention Brazil's Amazon Region Protected Areas (ARPA) program, which aims to establish new protected areas and sustainable natural resource management reserves, and is expected to carry over to Peru and Colombia.

The Canadian Boreal Forest Conservation Framework has also been singled out as one of the best wilderness conservation programs in the world, with the goal of protecting at least 50 percent of the Boreal in a network of large interconnected protected areas and sustainable communities.

But ultimately, the positive measures are too few and far between, and the researchers conclude that if current trends continue, there could be no globally significant wilderness areas left in less than a century.

"If we don't act soon, it will be all gone, and this is a disaster for conservation, for climate change, and for some of the most vulnerable human communities on the planet," says Watson. "We have a duty to act for our children and their children."

Let's hope Proxima b has a lot of trees…

The report has been published in Current Biology.