In a controversial move, Kuwait has passed a law making it mandatory for all its 1.3 million citizens and 2.9 million foreign residents to have their DNA entered onto a national database.

Anyone who refuses to submit their DNA for testing risks one year in prison and a fine of up to US$33,000, and those who provide a fake sample can be jailed for seven years.

The decision came after an Islamic State-led suicide bombing in Kuwait City on 26 June, which killed 26 people and wounded 227 more. The government hopes that the new database, which is projected to cost around US$400 million, will make it quicker and easier to make arrests in the future.

"We have approved the DNA testing law and approved the additional funding. We are prepared to approve anything needed to boost security measures in the country," independent MP Jamal al-Omar told AFP.

To fingerprint someone's DNA, scientists need to extract the genetic material from a small sample of their cells, and then map the unique combination of base pairs contained within - sort of like our own, super-long barcode. This allows police to compare DNA found at a crime scene with any DNA they have on file to look for a match.

However, the new law is sure to attract controversy from privacy and ethics advocates. Although many other countries around the world - including the US, UK, Sweden and Australia - all have databases that keep a record of the DNA of anyone who has been convicted of a crime, this is the first law that makes the database mandatory for all citizens.

In the European Union, such a database has been declared by illegal after the European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2008 that keeping a non-criminal's DNA sample "could not be regarded as necessary in a democratic society".

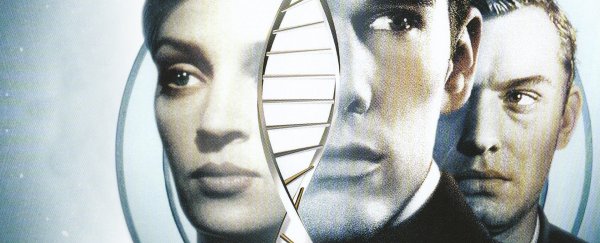

There are also concerns that this type of record could open up the possibility for governments to monitor their citizens' DNA - like in the 1997 sci-fi film Gattaca.

"If it's not regulated and the police can do whatever they want … they can use your DNA to infer things about your health, your ancestry, whether your kids are your kids," genetic researcher Yaniv Erlich from MIT in the US told the Associated Press on the subject of DNA databases back in 2013.

Currently, the US has the world's largest DNA database, containing entries from people who have been arrested, but not convicted, of crimes, as well as the DNA of missing persons and their families, and the deceased.

The way things are going now, we're going to need a whole lot more storage space for all the DNA we're keep tabs on.