On Earth we usually think of tidal forces in relation to the ocean and how they affect the ingress of waves along the shoreline – but those same forces over time can have far greater and even devastating consequences.

Researchers at NASA have announced that new modelling suggests that groove markings spotted on the surface of Phobos – the larger of the two moons orbiting Mars – are early signs that tidal forces exerted on Phobos by its proximity to Mars are slowly pulling the moon apart.

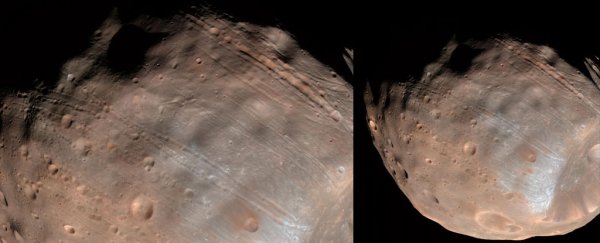

According to NASA, the scar-like crevices that have long been visible on Phobos' surface are evidence of an ongoing structural failure that will ultimately see the moon destroyed. The researchers say these grooves are like lunar "stretch marks" which reveal the effects of Mars' gravity pull, and which will progressively shatter the moon over the next 30 to 50 million years.

"We think that Phobos has already started to fail, and the first sign of this failure is the production of these grooves," said Terry Hurford of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Phobos' distinctive markings had previously been thought to be fracture lines stemming from the lunar impact that created the Stickney crater – a truly massive collision that almost destroyed the moon. Another more recent theory was the grooves were caused by impacts of smaller material ejected from Mars.

However, new modelling presented this week at the Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society's annual meeting suggests the deformations are instead caused by tidal forces. Interestingly, this theory was raised decades ago but was discounted after calculations – based on the assumption that Phobos had a solid core – negated the possibility that such fracturing could occur on a dense moon.

Now scientists believe Phobos is not dense but rather may have a rubble pile at its core, which is surrounded by a powdery surface regolith only about 100 metres thick.

"The funny thing about the result is that it shows Phobos has a kind of mildly cohesive outer fabric," said Erik Asphaug of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, Tempe, co-investigator of the study. "This makes sense when you think about powdery materials in microgravity, but it's quite non-intuitive."

Phobos orbits Mars at a distance of 6,000 kilometres – the smallest distance between a moon and a planet in our Solar System – and the gap closes by about 2 metres every century.

But while 30 to 50 million years might not sound like a particularly alarming death sentence for Phobos – and likely won't have consequences for a potential human colony on Mars – the more distressing implications of the research could be that the same phenomenon is happening in countless other systems throughout the Universe, including Neptune's moon Triton, which features similar markings and is also slowly being pulled inward.

"We can't image [extrasolar] distant planets to see what's going on, but this work can help us understand those systems," said Hurford, "because any kind of planet falling into its host star could get torn apart in the same way."