Small amounts of nuclear radiation spread across Europe last month, and no one can figure out why.

First detected over the Norway-Russia border in January, the radioactive Iodine-131 bloom was then found over several European countries, and while unsubstantiated rumours of nuclear testing by Russia have been cropping up, officials say it's most likely linked to an unreported pharmaceutical mishap.

While the radiation spike happened in January, officials in Finland and France have only just gone public with information on the incident, announcing that after the spike was detected in Norway, it appeared in Finland, Poland, Czechia (Czech Republic), Germany, France and Spain, until the end of January.

When asked why Norway didn't inform the public last month, when it was the first to detect the radiation in its northernmost county, Finnmark, Astrid Liland from the Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority told the Barents Observer:

"The measurements at Svanhovd in January were very, very low. So were the measurements made in neighbouring countries, like Finland. The levels raise no concern for humans or the environment. Therefore, we believe this had no news value."

As France's nuclear safety authority, the IRSN, announced last week, the actual amount of radioactive Iodine-131 in Europe's ground-level atmosphere in January "raise no health concerns", and has since returned to normal.

But what's most disconcerting about the event isn't the level of radiation that spread through Europe - it's the fact that no one can say what actually happened.

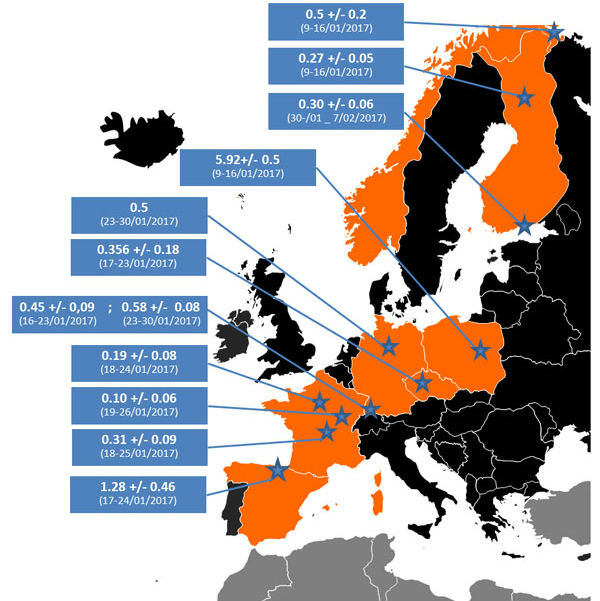

Iodine-131 (value +/- uncertainty) in the atmosphere. Credit: IRSN

Iodine-131 (value +/- uncertainty) in the atmosphere. Credit: IRSN

What we do know is that Iodine-131 has a half-life of just eight days, so detecting it in the atmosphere is proof of a recent release.

"The release was probably of recent origin. Further than this, it is impossible to speculate," Brian Gornall from Britain's Society for Radiological Protection told Ben Sullivan at Motherboard.

Right now, the best bet is that the origin of the radioactive Iodine-131 is somewhere in Eastern Europe - something that conspiracy theorists have latched onto as evidence that Russia performed a nuclear test in the Arctic.

But there is no evidence of this taking place, and the fact that only Iodine-131 - and no other radioactive substances - were detected strongly suggests this is not the answer.

"It was rough weather in the period when the measurements were made, so we can't trace the release back to a particular location. Measurements from several places in Europe might indicate it comes from Eastern Europe," Liland told the Barents Observer.

Based on the particular isotope, experts are saying it's far more likely that the radiation spike is the result of some kind of pharmaceutical factory leak, seeing as Iodine-131 is used widely in treating certain types of cancer.

"Since only Iodine-131 was measured, and no other radioactive substances, we think it originates from a pharmaceutical company producing radioactive drugs," Liland told Motherboard. "Iodine-131 is used for treatment of cancer."

And, oddly enough, the case for pharmaceuticals being behind the mess has a surprisingly similar parallel to back it up - an almost identical event occurred in 2011, when low levels of radioactive Iodine-131 were detected in several European countries for a few weeks.

At the time of the announcement, officials were also at a loss to explain the spike in Iodine-131, but quickly ruled out a link to nuclear power plants.

"If it came from a reactor we would find other elements in the air," Didier Champion, then head of environment and intervention at the IRSN, told Reuters in 2011.

Interestingly, a paper came out just last week confirming that the source of the 2011 Iodine-131 leak was a faulty filter system at the Institute of Isotopes Ltd in Budapest, Hungary, which produces a wide variety of radioactive isotopes for medical treatment and research.

The investigation is still ongoing for the 2017 leak, with the US Air Force deploying its WC-135 nuclear explosion 'sniffer' aircraft to the UK last week to help narrow down the source.

Hopefully researchers can nail down what exactly happened here, so factory owners - if they are to blame this time around - can ensure these kinds of leaks don't continue.

Because while both events posed no health risk to humans, it's really not something any manufacturer should be risking.