Our reliance on fossil fuels and the carbon dioxide that burning them produces has been one of the key drivers of climate change, but reversing the effects isn't quite as simple as stripping out all of the excess CO2 from the air. Researchers working at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany say that the planet's oceans will still be increasingly damaged thanks to the acid created by dissolving carbon dioxide.

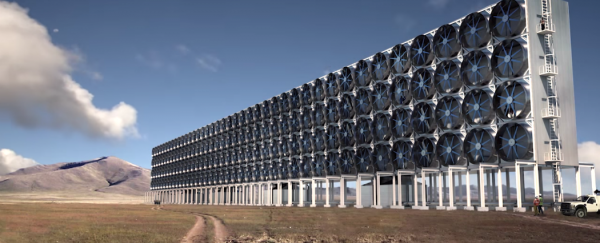

And that's assuming that we're able to come up with a way of artificially reducing carbon dioxide levels in the air in the first place. It's a puzzle many scientists are working on - entrepreneur Sir Richard Branson has promised £25m (AUD$53m) to the first team that can demonstrate an effective solution - but all of the potentially effective technology is still being developed. It's seen as a 'Plan B' if the nations of the world are unable to agree to significantly reduce their CO2 output.

"Geoengineering measures are currently being debated as a kind of last resort to avoid dangerous climate change - either in the case that policymakers find no agreement to cut CO2 emissions, or to delay the transformation of our energy systems," lead author of the study, Sabine Mathesius, said in a press release. "However, looking at the oceans we see that this approach carries great risks… even if the CO2 in the atmosphere would later on be reduced to the pre-industrial concentration, the acidity in the oceans could still be more than four times higher than the preindustrial level. It would take many centuries to get back into balance with the atmosphere."

In other words, even if Sir Richard's prize is claimed, it might not be enough to stop irreparable damage to the oceans of the world and the subaqueous life forms that rely on them. The study, which is published in Nature Climate Change, says that a drastic cutting down of the amount of CO2 released into the air in the first place is the only way to stop significant damage being done - marine ecology moves at a slow pace and long-term shifts can't be easily turned around with quick fix measures, no matter how technologically advanced.

"In the deep ocean, the chemical echo of this century's CO2 pollution will reverberate for thousands of years," adds co-author John Schellnhuber, director of the Potsdam Institute. "If we do not implement emissions reductions measures in line with the 2°C target in time, we will not be able to preserve ocean life as we know it."

Corals and shellfish are particularly at risk according to researchers, which would completely shift the balance of the underwater landscape and the food chain that relies on them.

That's not to say carbon removal techniques shouldn't be pursued as a way of helping reverse the effects of climate change, but they can't be relied upon to reset the delicate ecological balance of the planet, and reducing overall emissions at their source should still be the first priority.