Marijuana's official designation as a Schedule 1 drug – something with "no accepted medical use" – means it is pretty tough to study. Yet numerous anecdotal reports, as well as some studies, have linked marijuana with several purported health benefits, from pain relief to helping with certain forms of epilepsy.

Still, experts say more rigorous scientific analyses are needed. Use of marijuana, a psychoactive drug, can come with risks, especially in people who may be prone to addiction or mental illness. And now, for the first time, researchers have found a link between daily decade-long weed use and a difference in how the brain processes reward.

For years, researchers have suggested that such a link exists – and if it does, that it could play a powerful role in addiction. An important part of this line of thought is that addicts, far from amoral individuals incapable of making intelligent decisions, simply respond differently to drugs – neurologically, psychologically, physiologically – than people who are not addicted.

And this response is probably the result of many factors outside the person's control, including genetics, behaviour, and environment.

So for their study, published on Wednesday in the journal Human Brain Mapping, researchers at the Centre for BrainHealth at the University of Texas, Dallas, took a look at the brains of 53 daily long-term pot users (14 of whom met the American Psychiatric Association's criteria for addiction) and 68 people who'd never used the drug daily.

Then the researchers showed them a series of objects meant to test their reward response. The objects included one type of fruit (the "natural cue"), a pencil (the "neutral cue"), and either a bong, a pipe, or a joint (the "cannabis cue"), depending on which one the participant said they preferred.

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP/File

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP/File

Importantly, this study did not look at so-called recreational users – those who use the drug every few weeks or months. Instead, it focused on people who used the drug every day for an average of 12 years, several of whom met the criteria for being addicted to the drug, and many of whom displayed some signs of past or present problems with weed.

Why? Because the researchers wanted to tease out how changes to the brain's reward pathway might affect those who used the drug every day for years – and, more importantly, why.

Not surprisingly, when the chronic users were presented with either the bong, pipe, or joint, they displayed a stronger response in several parts of their brain linked with reward than they did when they were shown the fruit cues.

In contrast, the non-users did not show a significantly greater response to either the weed or fruit cues, and some parts of their brains showed a greater response to the fruit than to the bong, pipe, or joint.

"We found that marijuana disrupts the brain's natural reward circuitry, making marijuana highly salient to heavy users," Francesca Filbey, the director of cognitive neuroscience research of addictive disorders at the Centre for BrainHealth and an associate professor in the School of Behavioural and Brain Sciences, told Business Insider.

"In essence, these brain alterations could be a marker of transition from recreational marijuana use to problematic use," she said.

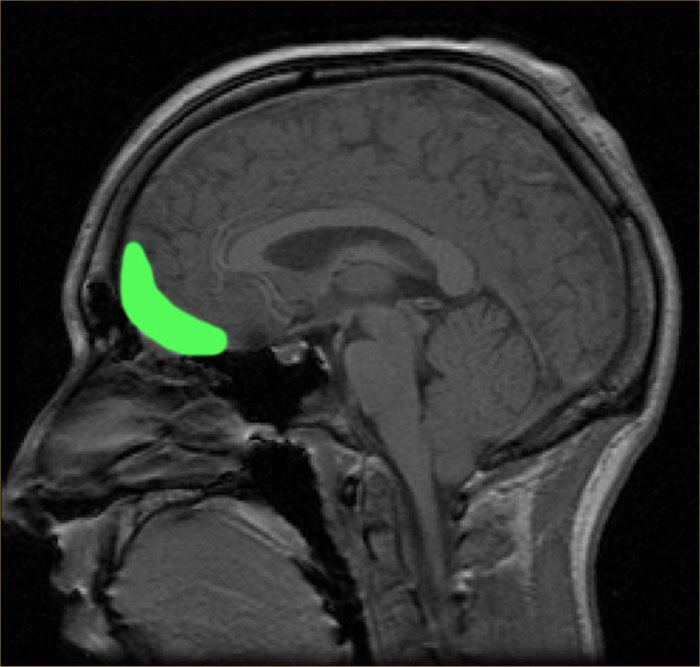

The orbitofrontal cortex, highlighted in green.

The orbitofrontal cortex, highlighted in green.

Marijuana and the brain

In another 2014 study also by Filbey, she and her team found that, compared with people who didn't use pot, long-term, heavy users tended to have a smaller orbitofrontal cortex, a brain region critical for processing emotions and making decisions.

And, interestingly enough, the heavy users also appeared to have more cross-brain connections. Scientists think regular users may develop these links as a means of compensating for the difference in size. The regular pot users also had lower IQ scores overall when compared with the people who didn't use the drug.

To arrive at their results – one of the first comprehensive, 3D pictures of the brains of adults who'd smoked weed at least four times a week, often multiple times a day, for years – the researchers used a combination of MRI-based brain scans.

Still, that study did not show that chronic weed use caused certain regions of the brain to shrink, or that pot use caused lower IQ scores – it simply showed a relationship among those factors.

"We cannot honestly say that that is what's happening here," Filbey told Business Insider in 2014.

Similarly, the latest study does not show that chronic pot use causes a change in the brain's reward response; the reverse could also be true, that the changed reward response influenced the chronic pot use.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: