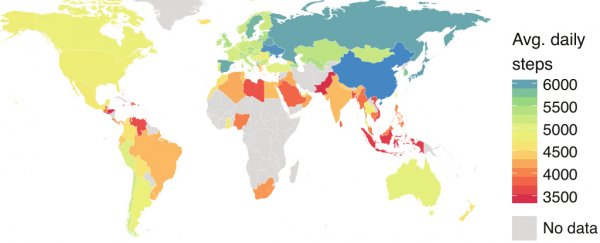

In what scientists say is the largest study of human movement ever conducted, researchers collected physical activity data from smartphone users in 111 countries – and discovered what they think could be a significant unrecognised public health risk.

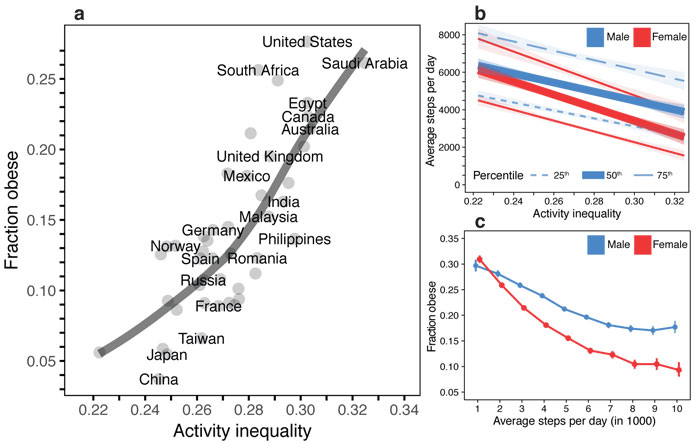

Analysing the level of activity of more than 700,000 people, the team found it wasn't the average level of physical activity in each country that proved the biggest predictor of obesity – it was the amount of "activity inequality" within each population that increased the prevalence of obesity.

"If you think about some people in a country as 'activity rich' and others as 'activity poor,' the size of the gap between them is a strong indicator of obesity levels in that society," explains bioengineer Scott Delp from Stanford University.

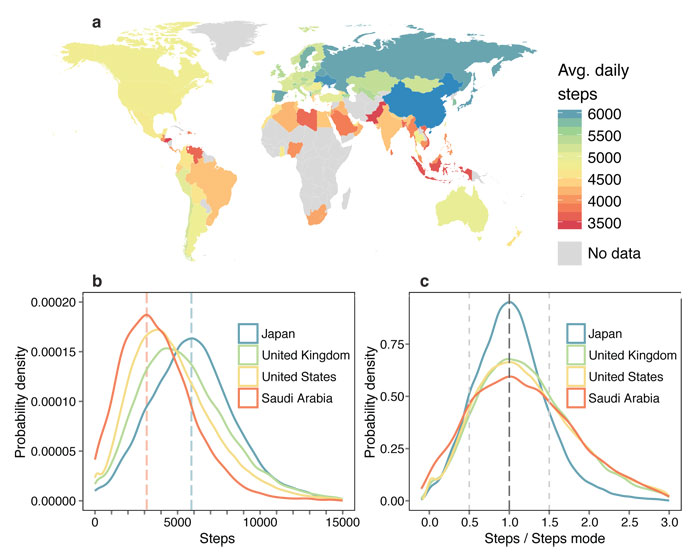

To figure this out, the researchers collected anonymised health data tracked by the free Azumio Argus activity monitor app.

Users of the app had their daily step counts recorded by the accelerometer in the smartphone, which were provided to the researchers, along with basic information about their age, gender, height, and weight.

T Althoff et al, Stanford University

T Althoff et al, Stanford University

When they compiled the data, the team noticed that in countries with little obesity, people tended to walk about the same amount each day. In other countries, though, where there were bigger gaps between those who walked a lot and those who walked only a little, obesity was significantly more of a problem.

This correlation persisted even when the average level of steps taken was the same across countries – showing that while national physical activity averages might seem like a reasonable way of comparing countries' level of fitness, by themselves they aren't at all reliable for gauging obesity prevalence.

Of the 46 countries represented with results from at least 1,000 app users, the five countries with the highest levels of activity inequality were Saudi Arabia, then Australia, Canada, Egypt (all equal second), and the US.

At the other end of the scale – where more evenly distributed patterns of physical activity correlate with lower prevalence of unhealthy weight gain – Hong Kong leads the list, followed by China, Sweden, South Korea, and Czechia.

You can find a full breakdown of the activity inequality listings here – along with a lot more data collected by the study here.

T Althoff et al, Stanford University

T Althoff et al, Stanford University

While activity inequality isn't a good thing for anybody, statistically it's worse for women than it is for men, the researchers found.

"When activity inequality is greatest, women's activity is reduced much more dramatically than men's activity," says one of the team, computer scientist Jure Leskovec, "and thus the negative connections to obesity can affect women more greatly."

Of course, despite the obvious value of this record-setting data set, it's worth bearing in mind some of the limitations that come with taking such a broad view fuelled largely by smartphone data.

Chiefly, smartphone accelerometers and the apps built around them aren't always entirely accurate in measuring different people's steps – and all the data looked at here was sourced from users who voluntarily chose to use the Argus app, meaning they're not necessarily representative of society at large.

That said, this research does at least tell us a lot that we didn't know about varying contrasts of physical activity in a lot of countries – at least among those who use smartphone activity apps, that is (but hey, that's a lot of us) – and could help steer future health research to addressing the issue of activity inequality.

In the meantime, the scientists say the global average step count is 5,000 steps taken daily. On whichever side of that figure you fall, why not try to see if you can improve your number a little bit more?

Just make sure to try to encourage your family, friends, and anybody else around you to also join in – because getting everybody on board with physical activity seems to be even more important than we realised.

The findings are reported in Nature, and you can access data from the study here.