Rain showers can sometimes take a bizarre turn: in very rare cases, animals such as fish and frogs have been known to fall from the sky alongside water droplets, and around the world, people have experienced what's known as blood rain, where the water has a peculiar red tinge.

Reports of blood rain have been recorded for centuries - back before humans knew any better, it was believed the sky was actually spitting out blood. Nowadays, we have the technology to analyse the composition of blood rain so we no longer have to jump to any crazy conclusions, but scientists are only just figuring out how and why it occurs. And now a new study has put forward an explanation for a recent incident in Zamora, a city in northwestern Spain.

The people of Zamora and several nearby villages noticed blood rain falling from the sky late last year: was it chemical pollution? Was it some kind of deliberate sabotage? Was it a sign from God? A concerned resident sent a sample of collected rainwater to scientists at Spain's University of Salamanca to see if they could come up with any answers. And now the results are in.

The researchers say a freshwater green microalgae called Haematococcus pluvialis is to blame - this microalgae is capable of producing a red carotene pigment called astaxanthin when in a state of stress, perhaps caused by getting caught up in a raincloud.

That matches up with previous studies of blood rain, one of which found the microalgae Trentepohlia annulata to be the cause of an incident in Kerala in India - different kinds of microalgae, but the same root cause.

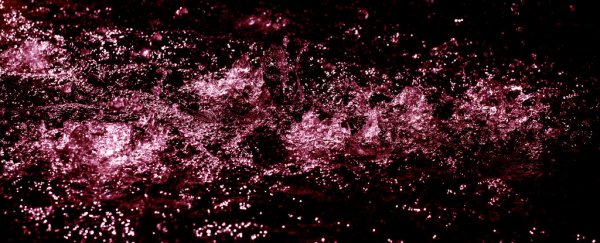

Astaxanthin in H. pluvialis. Credit: Frank Fox/Wikimedia

Astaxanthin in H. pluvialis. Credit: Frank Fox/Wikimedia

What's less clear is how these microalgae spores are travelling. H. pluvialis is not native to Zamora or any of the neighbouring regions, and before the Kerala incident, T. annulata was thought to only exist in Austria - a long way from India. So now the researchers have to figure out exactly how these mysterious microorganisms are making their way across the globe.

Hitching a ride on global wind currents would be a good bet, but so far researchers have been unable to find any concrete proof of this. The researchers identified a prevailing current that could've carried the microalgae out from North America to Spain, but have yet to pinpoint the exact source. Their work has been published in the Spanish Royal Society of Natural History Journal.

In the meantime, there's no cause for panic if you're caught in a blood rain shower: H. pluvialis is non-toxic and is often used as a food source for salmon and trout to give them a more pinkish hue. Indeed, motorcycle company Yamaha recently used the microalgae to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from its factories.

Blood rain puddle from Zamora. Credit: Joaquín Pérez

Blood rain puddle from Zamora. Credit: Joaquín Pérez