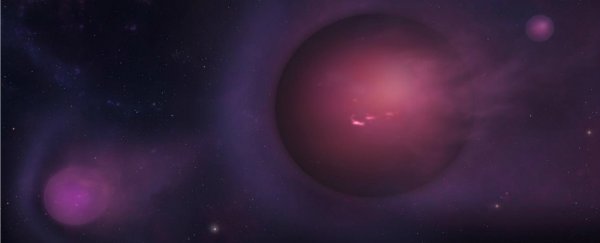

Astronomers have found evidence that the Milky Way's black hole might be propelling giant, planet-sized objects into the Universe – and there could be one just a few hundred light-years from Earth.

These planetary 'spitballs' haven't been directly detected as yet, but calculations suggest they could weigh as much as several Jupiters each. They form when the black hole emits a streamer of gas that can whip around itself and bundle into a large object before blasting off into space.

"A single shredded star can form hundreds of these planet-mass objects. We wondered: Where do they end up? How close do they come to us? We developed a computer code to answer those questions," said lead study author Eden Girma from Harvard University.

The process Girma describes happens when a star ventures too close to a black hole and gets sucked towards it by the black hole's immense gravitational pull.

When this happens, the star is stripped of its gases, creating a gigantic streamer that is flung outward into space. As this streamer moves out of the black hole, the gases can possibly ball up into planet-sized objects, that are then thrown away from the black hole at intense speeds.

If her calculations are correct, these 'planet-mass objects' end up flying away from the black holes that created them at about 32 million kilometres per hour (20 million mph), causing around 95 percent of them to leave the galaxy they were born in and fly towards neighbouring ones.

For the Milky Way, that neighbour would be Andromeda, locking the galaxies into a cosmic spitball battle.

"Other galaxies like Andromeda are shooting these 'spitballs' at us all the time," said one of the team, James Guillochon from the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics.

The team calculates that some of the objects could lie within a few hundred light-years of Earth, and they might faintly glow from all of the heat that is created during their formation.

They hope that future telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, might find some of them in the years ahead.

But despite being similar in mass to regular planets, these objects would be very different – mainly because they're made from the gases of stars and wouldn't have a rocky core, which is at the centre of gas giants such as Jupiter.

The team also notes that the objects are formed at much greater speeds than traditional planets that can take millions of years to come together.

They say that a black hole can strip a star of its gases in less than an Earth day, and that the gases could reform into objects in under a year before getting shot into the cosmos. That's incredibly fast, especially for cosmic reactions.

"Only about one out of 1,000 free-floating planets will be one of these second-generation oddballs," Girma said.

The team's work has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, but they presented it last week at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Texas, giving the astronomy community the chance to provide feedback on the results.

So until they're verified and published, we have to take their findings with a grain of salt.

But if their calculations do turn out to be correct, they could help us better understand how black holes operate, and how their ability to strip gases from stars might actually cause a rebirth of new objects.

The next step will be to hopefully spot one of these hypothetical objects as we get better and better telescopes. We can't wait.