Researchers have found something strange going on inside Washington's Mount St. Helens. Despite being responsible for the deadliest eruption in US history, and the most active volcano in North America's Cascade Arc, the volcano is actually cold inside.

It appears Mount St. Helens is stealing its heat from somewhere else, but researchers still aren't sure why or how.

"This hasn't really been seen below any active arc volcanoes before," geologist Steven Hansen from the University of New Mexico told Science News.

The new mystery adds to the anomaly that is Mount St. Helens - the volcano that caused the US's deadliest eruption in 1980, killing 57 people and causing billions of dollars worth of property damage.

The volcano was already considered odd because of its location.

It's part of the Cascade Arc, a string of volcanoes that runs parallel to the Cascadia subduction zone from California to British Columbia, but for some reason, Mount St. Helens sits 50 km (31 miles) to the west of the rest of the arc's mountains, which lie in a nice, orderly north-south line.

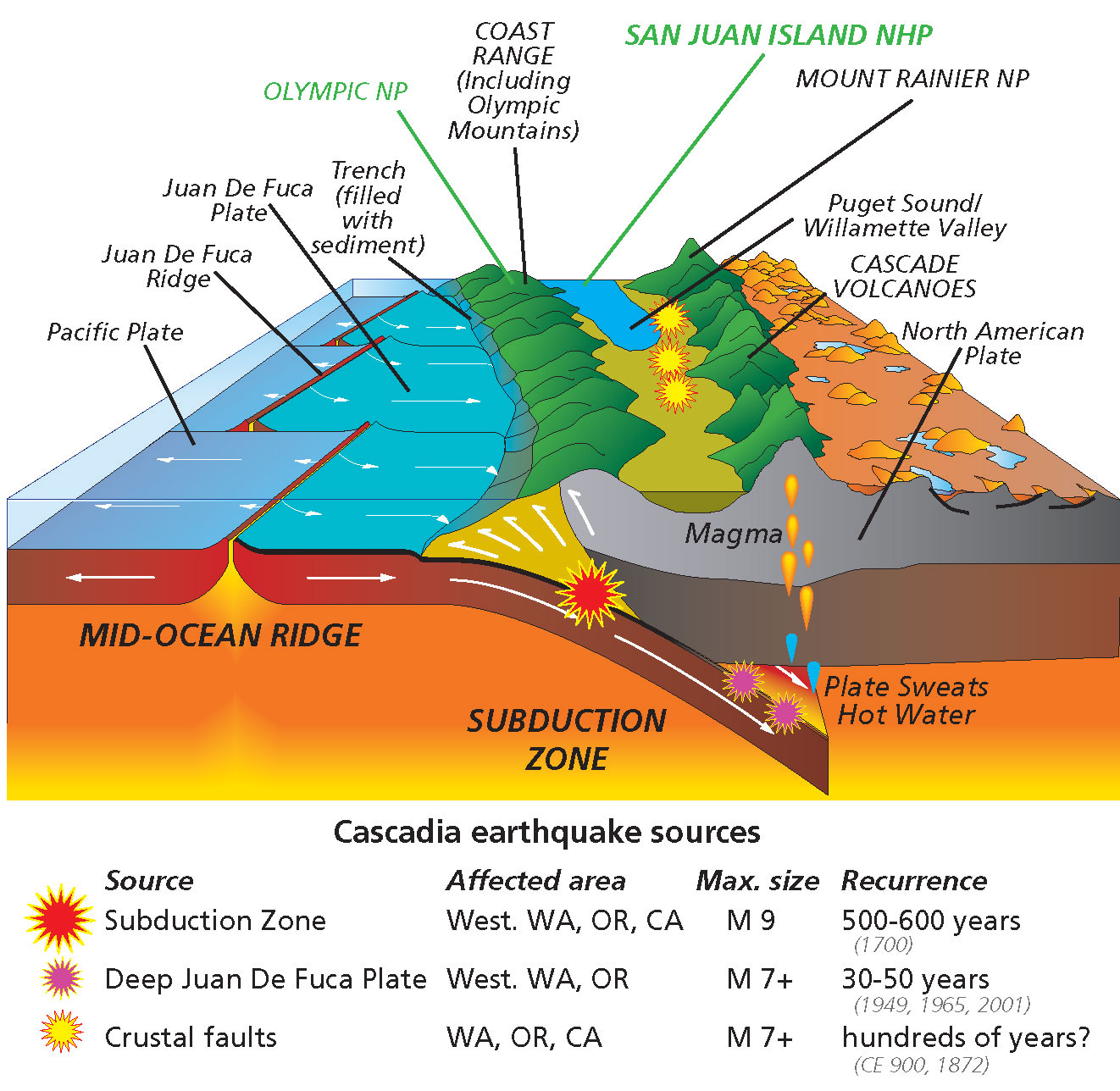

The Cascade Arc is right on top of a geologically active region where the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate nudges under the North American plate, forcing scorching hot pieces of mantle towards the surface where they melt into magma.

But Mount St. Helens is on top of a wedge of cold mantle, and researchers have never understood why it's located where it is.

NPS/R. J. Lillie, Parks and Plates (2005)

NPS/R. J. Lillie, Parks and Plates (2005)

To figure out what was going on, in 2014, Hansen and his team deployed thousands of sensors around the mountain to measure ground movements. They then drilled 23 holes into the volcano, and filled them with explosives to trigger mini quakes around the volcano.

This allowed them to monitor exactly how the seismic waves travelled through the interior structure of the mountain, and get an understanding of the temperature and type of material within.

Those seismic waves painted a pretty strange picture - instead of a chamber of hot magma below the volcano, the team found a cool wedge of serpentine rock.

Given its eruptive history, the results don't really make sense, and researchers are now trying to figure out where Mount St. Helens gets its fuel.

The researchers suggest that the magma source most likely lies to the east, near the rest of the Cascade Arc, where there are magma temperatures above 800 degrees Celsius (1,470 degrees Fahrenheit).

But they still have no idea why the magma would be travelling 50 km (30 miles) to the west in order to erupt out of Mount St. Helens.

They think it might have something to do with deep earthquakes in the region, but they need to get more data to even being to understand what's going on.

Hansen and his colleagues will continue to monitor the earthquake as part of the Imaging Magma Under St Helens project, and are hoping that they'll eventually be able to explain where the volcano gets its fire - and perhaps better understand volcanoes elsewhere in the world.

For now, though, the mountain remains a mystery.

"Mount St. Helens is pretty unusual," Hansen told Maddie Stone over at Gizmodo. "It's telling us something about how the arc system is behaving, and we don't yet know what that something is."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.