Dental analysis of a 1.2-million-year-old tooth that once belonged to one of our early human ancestors has yielded new information about what ancient hominins used to eat - and it doesn't sound all that appetising.

According to a new study, tartar build-up on the tooth shows that raw meat and vegetables were on the menu, alongside bits of wood, scales from butterfly wings, and parts of an insect's leg.

"Evidence for plant use at this time is very limited, and this study has revealed the earliest direct evidence for foods consumed in the genus Homo," the team, led by Karen Hardy from the Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain, reports.

"All food was eaten raw, and there is no evidence for processing of the starch granules which are intact and undamaged."

While an understanding of diet is helpful to piece together how our ancient ancestors lived, the key suggestion here is that ancient tartar provides evidence that fire was not in use in Europe 1.2 million years ago.

Exactly when in human prehistory fire started to be used for cooking and warming purposes has been widely debated, with some researchers suggesting that it goes back 1.8 million years.

The earliest direct archaeological evidence of fire has been dated to 800,000 years ago, and if these tartar-encrusted teeth are evidence of a lack of fire, it suggests that fire technology took off somewhere between 1.2 million to 800,000 years ago, but no one is entirely sure.

The team also suggests that, since the toothbrush wasn't invented yet, early hominins used sticks and twigs as toothpicks to keep their teeth in check - an act that researchers previously only had evidence of from roughly 49,000 years ago.

"Additional biographical detail includes fragments of non-edible wood found adjacent to an interproximal groove suggesting oral hygiene activities, while plant fibres may be linked to raw material processing," the team writes.

The tooth came from a jaw bone found at the Sima del Elefante excavation site in Spain's Atapeurca Mountains, which contains some of the oldest early human remains ever found.

The researchers performed their analysis by taking a sample of dental calculus - better known as tartar, a form of hardened plaque - that they removed from the tooth using an ultrasonic scaler, a pointy, rather intimidating piece of dental equipment that buzzes plaque away.

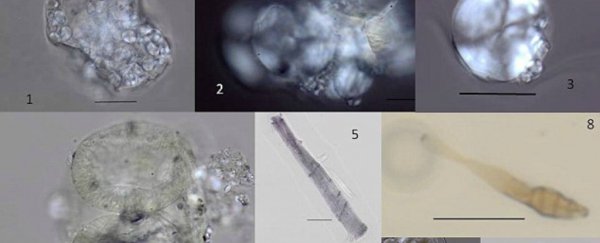

Next, they performed various scans on the tartar to reveal microfossils hidden within it. This is where they found bits of wood, animal tissue, and even a small plant pathogen known as Alternaria, associated with asthma and hay fever.

While there isn't enough taxonomic evidence to accurately identify the species of early human that the bones came from, the evidence suggests that this ancient hominin's diet consisted of mainly raw foods, because they had yet to start cooking over a fire.

Even without the luxury of cooking, the tooth shows a pretty broad diet, including seeds, plants, and animals.

"It is plausible that these ancient grasses were ingested as food," Hardy said of the fibres. "Grasses produce abundant seeds in a compact head, which may be conveniently chewed, especially before the seeds mature fully, dry out, and scatter."

"Our evidence for the consumption of at least two different starchy plants, in addition to the direct evidence for consumption of meat and of plant-based raw materials suggests that this very early European hominin population had a detailed understanding of its surroundings and a broad diet."

Hopefully, as the studies of the bones found at Sima del Elefante continue, we'll gain a better understanding of how our early ancestors lived, ate, and died, providing a more complete picture of our past.

The research was published in The Science of Nature.